We gathered on a conference call to view a highlight video of our users using our site—a video gathered by our new online survey tool. The voice of the business leader on our conference call became excited as the possibilities for the new videos began to sink in. “I know! Let’s use a compilation of these videos from our online survey tool to show the executive team.”

“Wait, what?” I thought. “Can we do that?” My radar had been alerted; my alarms rang. I was about to play Cassandra, the doom and gloom prophet, once again.

“I have some concerns, folks. We need to look at the rights that they agreed to when they signed the informed consent. We have to be sure our vendor feels that’s acceptable. Who owns these videos? We should ensure that we aren’t revealing personal data. Even if they agreed and we do have the rights to use the videos, we have to take a moment to ensure that the content is appropriate; that the content doesn’t place participants at risk or at a disadvantage. This could be tricky.”

If you listened carefully, you could actually hear the eye rolls. Everyone loves Cassandra.

Big Data, Big Ethics

We have an array of so-called “big data” user experience research tools at our disposal: large-sample, unmoderated testing tools, intercept survey tools, and an increasing number of metered Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) that allow you to conduct A/B testing on live products. Although moderated usability testing provides us with foundational insights, these tools have seen growth in the last decade due to increasing demand for Agile and lean testing, and for testing within budget demands.

I’m excited to take advantage of them. At the same time, I am becoming aware of the new ethical challenges that they present. What are the best ways to ensure that we maintain the high standards of care and safety that we follow when we conduct research using older, more familiar methods? As we use them for research, how do we ensure that we:

- First, do no harm?

- Inform the participants properly about the research goals and risks?

- Get the participants’ truly informed consent?

- Ensure the privacy and security of their data for them?

Contemporary Ethical Practice: Making Human Subject Guidelines Our Own

In the moderated world, we based our ethical treatment of participants on the guidelines developed for human subjects of government-sponsored research, the Human Subject Guidelines. (Read the American Psychological Association Guidelines, for example.) These had been developed following several examples of egregious violations of human rights in the name of scientific research.

While our research often does not meet the definition of scientific research, the guidelines were both sensible and fairly easy to adapt to our work. In fact, most academic work had to meet a very strict version of these, complete with formal reviews by an institutional review board (IRB) and oversight. Our guidelines for protecting participants boil down to a more succinct, but essentially similar version:

- Tell each participant what you are doing and the reason for doing it. Describe how the process will work. Explain any risks the participant will experience, and if there are any benefits.

- Inform each participant how you will gather the data and who will have access to the data. That also includes informing the participant who may be observing at that moment and how.

- Inform the participant how you plan to keep his or her data and when you will no longer keep the data. Describe how you will keep it secure and how you will dispose of it and when.

- Inform the participant of his/her right to refuse to do this and inform the participant that he/she has the right to stop, to take a break, or to refuse to do anything that they find unacceptable.

- Gain their agreement to be recorded or negotiate terms of how the data may be gathered. For example, if the participant does not want a face recorded, turn off the camera.

I have a boilerplate informed consent script and form; most of us use something similar. It is an expression of our empathy for users that we take our responsibility here seriously. Every year, I dutifully review my data and I make sure that I follow my own and my company’s data policies. More importantly, I look each participant in the eyes and reassure them that we are doing good for what is usually a small risk to each of them (usually, the possibility that they might be shown to be less of an expert than their self-image).

How do we do the same for our newest tools? I mentioned three types of data tools: live A/B testing, large sample unmoderated testing, and survey intercept tools. Each has its own risks, and possible mitigations.

Live A/B Testing

This is where my heartburn is the greatest. Live products are manipulated with different UI elements, flows, or other features in a head-to-head comparison released to similar, controlled audiences of users. Measures usually focus on desired behaviors like conversions. These actions can have unintended consequences, and participants may resent being part of an experiment while conducting their everyday business. If participants are not explicitly participating, they may react negatively.

We recently saw two very public examples in the news. Two large companies were put under fire for their apparent breach of ethics. In 2012, Facebook employees published a study in which they admitted to measuring responses to positive or negative stories. OKCupid suggested matches for potential dates that their own tools suggested were a poor match for users. Understandably, users said they lost trust in both sites, and each were forced to rethink their policies. You can read more here: http://www.digital-tonic.co.uk/digital-tonic-blog/the-ethics-of-experimentation/

Even seemingly innocuous Live A/B testing (see Figure 1 for a possible example), may produce negative results. Imagine the risks inherent in the examples below.

If A or B is less visible, perceivable, accessible, or has poorer affordance, the participant may be harmed in some minor or major way. For example: in healthcare, the participant fails to see the button because of its reduction in size in favor of marketing. Consider the risk: A needed prescription isn’t filled in a timely way, resulting in an adverse health event. (Note that something similar might happen in any industry that deals with intensely personal information: financial, automotive, certain types of retail sales, and more.)

Possible mitigation: To avoid placing participants at risk, test prototypes with informed consent. If live A/B testing, plan a review board that understands how user experience and accessibility problems can affect participants.

“Participants” do not consent to being part of the test. In A/B testing, the agreement to participate likely came with our agreement to the terms. Can you state with precision where you’ve agreed to participate in live A/B testing and where you haven’t? In many cases, we like to believe that agreement to Terms and Conditions ends our responsibility. I will argue that live A/B testing means that we can no longer accept that assumption

Possible mitigation: Consent is only given when the participant is informed. We need to consider how to be as explicit as possible in gathering agreement. Legally, the terms and conditions may make things legal, but not ethical. Ethically conducted studies happen when consent is given explicitly.

Large Sample, Unmoderated Testing

Introduction of personal data places the participant at risk. In my work, the tool we use does not permit the use of sensitive personal data. However, I believe that risk is still possible.

Risk 1: Exposing Personal Data

In moderated testing, we usually instruct our participants to make up realistic data. However, I have observed that people often give me their personal information by mistake and I need to prompt them to avoid revealing anything personal.

Possible Mitigation: Made-up data or test accounts. Whether users are told to enter specific fake data or you ask them to make it up on the fly, fake data mitigates personal data problems to the degree that the participant remembers to enter made up data.

A test account requires specific login and other bits of information specific to the account, but avoids the problem of introducing personal information. Participants will need some method for remembering the specific information when it is needed, usually by writing it down or printing it out.

Possible Mitigation: With any of these methods, explicit instruction in the tool’s user interface helps the users avoid errors.

Risk 2: Security

We also need to be sure that our new tools and systems are secure. Now that the system is not typically within our own networks—owned by us—we need to ensure that our vendors understand security and take it seriously.

Possible Mitigation: Include privacy and security as part of your vendor evaluation checklist. Remember to keep all data, including the data gathered by your vendor, as secure as your own.

Items to consider:

- Is personally identifiable information stored by the tool? How is that handled?

- How is the data stored? Is it kept securely?

- Who, besides you, has access to what data? How is that information managed and stored?

- If you download data, how will you plan to secure and store that information?

Risk 3. Undue Test Stress

Undue stress is possible during any user research. Unmoderated testing, for example, throws participants into the fray with whatever context they bring with them.

In moderated testing, I often find that we need to provide context, even to the point of role-playing. For example, it is easier to imagine paying for professional services with credit if you can imagine standing in the dentist’s office following an expensive procedure.

In unmoderated testing, these circumstances can’t be replicated. We can’t role play or clarify. What context can be provided must be explicit and easy to understand or imagine. Without that, the participant may feel undue frustration and negative emotions from the lack of context.

Possible Mitigation: Think about the goals of testing. Some tasks may not be suited to unmoderated testing; others may need adjustment from the presentation you would provide in a moderated test. Recruit from the pool of participants that understands the context. (For instance, as in my dental office example, people who have had dental procedures recently.) Provide explicit instructions; test the instructions while you observe your test. Find out from a pilot sample of users what worked well and where gaps exist in their understanding of your scenario.

Another source of undue stress may develop from the technology itself. Most tools layer a button or dialog box over your product to allow participants to see your product, but navigate through the task. It may be hard to see the task, the product, or to manipulate the task window. If you provide specific data to complete forms, using and remembering the data may be more difficult.

Possible Mitigation: Keep the tasks simple and the instructions plain and clear. Provide the information necessary separately, perhaps by email, or encourage the participants to record the information you want them to use. Consider our technique: “Please make up the data, but try to make it realistic.” The participant is instructed to complete the form with fictitious, but realistic information. That removes the burden of having to find or remember what to do, yet provides us with the ability to see whether the participant knows how.

Survey Intercept Tools

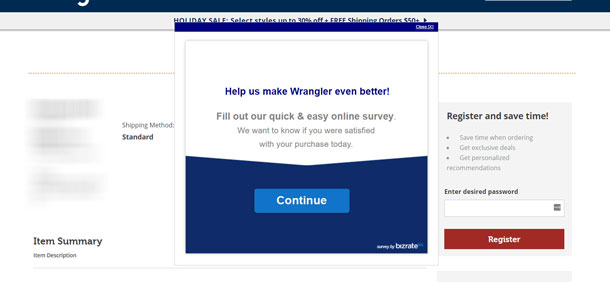

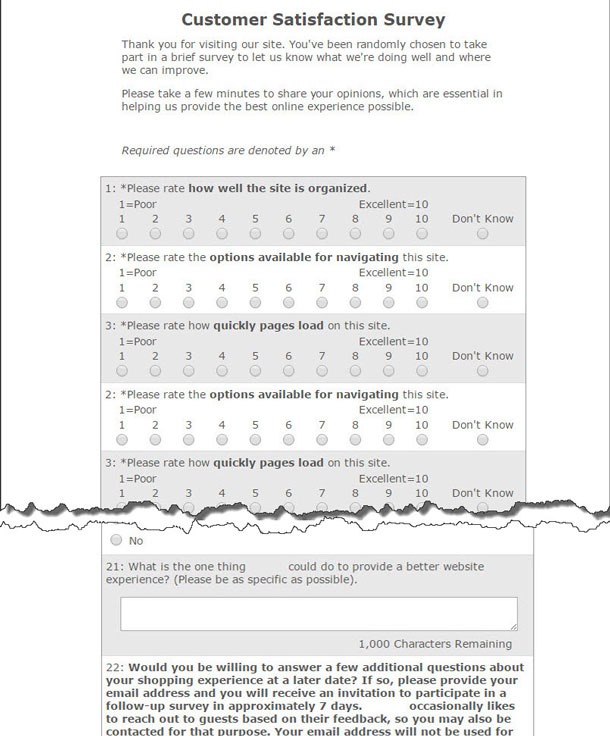

Most sites use some sort of survey intercept to keep an eye on their digital properties. These tools interrupt users upon some sort of trigger—like viewing a number of pages—to pop over a dialog to ask them to provide feedback. Over time, large numbers of respondents provide feedback and the findings can be helpful in spotting issues and keeping an eye on satisfaction. But they, too, pose ethical problems.

The first is invasiveness and effort: We are interrupting a user to ask for data. (See Figures 3 and 4.) It is a huge ask and it is disrespectful to take more time and effort from them than is absolutely necessary. Unfortunately, I have sat in on intercept survey planning meetings where business leaders wanted to get such specific insights that the survey itself was far too long.

Possible Mitigation: Remember that every question asked becomes a burden of time. Is each question necessary for you to achieve your data gathering goals? Pare them to their minimum; choose tools that understand minimalism.

Some intercept survey tools allow clients to gather live video. While the participant has to explicitly agree to being recorded, all the same responsibility toward privacy, security, and informed consent associated with live testing apply here. The user must understand what they agree to.

Possible mitigation: We must be clear about who owns the video and how it will be stored and managed. The participant must agree to this, as well.

UX as Ethical Gatekeeper

As the user experience professional, when the business wants to let videos wander (in other words, business leaders or other well-intentioned team members want to use the video in a way that the participant didn’t agree to), someone must serve as gatekeeper.

Whenever these moments occur, our UX Cassandra role should compel us to represent not only our users’ need for great user experience, but for proper ethical handling of their participation in our experiments. Each of our new tools provide ethical challenges. We have an obligation to consider their challenges and address them as seriously as we do with our live participant studies or any of our methods.

[bluebox]

The UXPA Code of Conduct can be helpful as our foundation. It says:

- Act in the best interest of everyone

- Be honest with everyone

- Do no harm and if possible provide benefits

- Act with integrity

- Avoid conflicts of interest

- Respect privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity

- Provide all resultant data

[/bluebox]

Conversations have started; I am not the first to consider the implications of big data testing. We may be able to continue this discussion with some smart folks I know at our next UXPA Conference, where we may be able to add your thinking as well.

- Consider that all of the steps you take with moderated testing will probably present themselves here; be ready to consider the ethics of whatever new challenge comes our way.

- Whatever tool you may use, be sure your participants have given truly informed consent.

- Carefully review plans for live product testing to ensure that participants are not placed at a disadvantage, that you have not introduced an accessibility or usability issue, and that all of the design changes proposed do not violate policy or law.

- Be mindful of the burden we ask of our unmoderated participants. Be concise, explicit, and plain in instructions.

- Manage resulting data professionally; develop policies and procedures for keeping data safe and sound. Ensure that personal data is not used or is managed securely—in fact, with the highest security possible.

There is likely more to consider. I hope to continue the conversation and add more to this humble beginning.