The Internet offers a useful way to share and consume complex health information. Not only can health information be found through popular search engines, such as Google, but hospitals and doctors can also provide their patients with specific health information through the Web via patient portals and hospital websites. However, information is not always shared in such a way that is useful for the end user. Websites often include complex health jargon with the expectation that since it is available, it is usable. However, as many user experience practitioners are aware, simply putting information on the Internet does not make it usable.

One area of our research is the use of illustrations to aid in the understanding of complex health-related text. In this article, we discuss the results of various studies that examined the role of illustrations in understanding complex online health information. We will highlight the main findings covering three areas:

- Using illustrations in online health information

- Measuring user experience

- Lessons learned from using illustrations

Using Illustrations in Online Health Information

Illustrations are widely used online. While the majority of online information is still largely textual, text is often accompanied by photos, graphics, diagrams, and other types of visualizations. Illustrations have the potential to attract attention, facilitate learning, increase enjoyment and engagement, and accommodate poor readers. Since most health information often includes complex language or medical jargon, illustrations play a crucial role in the effectiveness of communicating health information on websites. This is especially the case for people who have difficulties using online health information in general, such as people with limited health literacy skills and older adults who might experience natural age-related cognitive decline.

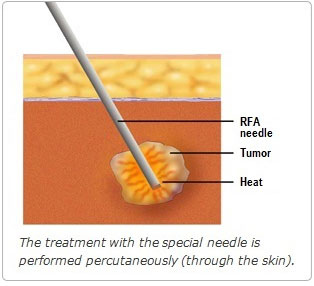

But what does it mean to have illustrations on a webpage? Do they guarantee success, and if so, what kind of success? Are all types of illustrations equally effective? For whom are illustrations worthwhile? These questions show the diversity of elements that UX practitioners should consider when using illustrations in online health information. We researched two specific types of illustrations: illustrations that aim to explain (cognitive illustrations) and illustrations that are intended to enhance enjoyment (affective illustrations). For example, a cognitive illustration can be a drawing of a complex procedure and an affective illustration can be a photo of a doctor-patient interaction (see Table 1). Consider both types of illustrations when providing information online because both have the potential to alter how people consume and understand complex information. However, do not assume that merely adding images is sufficient for all users.

Table 1. Cognitive and affective illustrations

| Type of Illustration | Definition |

|

A cognitive illustration can be referred to as a picture, photo, or drawing that aims to explain (parts of) textual information.

Cognitive illustrations help to give a better understanding of online health information sources and may improve memory for medical information. These illustrations often use arrows or words to refer to textual information. |

|

An affective illustration is most often a text-irrelevant photo that aims to enhance enjoyment and positive emotions from information that is displayed on websites.

Affective illustrations do not directly aim to enhance learning from websites, but may indirectly do so by making a website more attractive and interesting for web users. |

Measuring User Experience

Even though there seems to be a general consensus that “illustrations are worth a thousand words,” studies have shown inconsistent results regarding the effectiveness of using illustrations. Whereas some studies report positive effects of illustrations (for example in terms of improved memory, comprehension, and attention), other studies fail to find evidence for such effects or even demonstrate contradictory effects. While pre-testing affective illustrations for our studies, a 61-year-old female patient said about one of the affective illustrations, “This doctor appears friendly, competent, and careful,” while a 54-year-old female patient shared a comment about the same illustration: “A smiling doctor is non-information…remove this picture, I would say. If this illustration is attempting to give the feeling of good care, it is not working for me.” We discovered that there are individual differences in the extent to which certain images are helpful and desired.

Therefore, it is important to understand that illustrations have a certain effect on various users and that people differ in their needs and preferences when looking for and consuming online health information. Eye-tracking and think-aloud protocols can help us gain more insight into how online health information is used and for whom illustrations are most beneficial.

How are illustrations used?

There is ample evidence that users pay more attention to text-illustrated information than text-only information. Illustrations may help to attract the reader’s attention or direct attention to text-relevant pieces of information. Illustrations can also be used as a cue to read pieces of information when the accompanying illustration arouses interest. We recently conducted a think-aloud study where we asked participants to think out loud while navigating a health website. Overall, we found that illustrations were perceived as useful, and sometimes even necessary, for comprehending complex text information.

However, in a recent eye-tracking study among 61 Dutch adults, we found that adding cognitive illustrations to a webpage did not increase the total time spent on the webpage. Simply adding extra elements to a webpage might attract or direct attention, but this does not necessarily mean that people will spend more time on the website overall, or that the images help users understand the information. The effectiveness of text-illustrated information cannot be fully explained by mere attention to illustrations.

In another eye-tracking study among 10 younger and 10 older US adults, we compared levels of attention between cognitive and affective illustrations. We found that overall users spent only some of the total time on the webpage looking at the illustrations. Moreover, there was a difference in the amount of attention to the cognitive versus the affective illustrations: whereas cognitive illustrations received some attention, affective illustrations were nearly ignored (see Figure 1).

For whom are illustrations beneficial?

When we broadly believe that illustrations are effective, we assume that every reader makes active use of illustrations when they are present. But as shown in the examples above, we already know that some types of illustrations simply do not receive much attention. So then who actually makes use of illustrations and for whom do they lead to positive outcomes?

As illustrations may provide a compensatory function, we might expect that illustrations are particularly helpful for poor readers. On the other hand, research suggests that illustrations are especially helpful for good readers who can effectively integrate illustrations with text to establish a complete understanding of the information. Ultimately, illustrations provide different readers with various benefits. For instance, we have shown that when people with adequate health literacy view illustrations that accompany complex text, they spend less time reading text information and yet still recall the same amount of information as when they spend more time reading text information with no illustrations. However, illustrations appear to be more helpful for people with limited health literacy: when they attend to illustrations, they recall more of the text-illustrated information compared to when no illustrations are available.

It is also suggested that older adults might especially benefit from illustrations. Older adults are considered vulnerable for poor online health communication due to declining basic cognitive abilities and less experience with Internet technologies. With potentially diminished total cognitive capacity, older adults may benefit from having both verbal (text) and visual (illustrations) information. Yet our eye-tracking data show that older adults spend less time looking at illustrations than their younger counterparts. Interestingly, when they spend enough time reading text information, older adults in particular remember information more accurately. In these data, illustrations were only found to be beneficial for younger adults.

Lessons Learned From Using Illustrations

So what does it mean to include illustrations on a webpage? Do they guarantee success and if so, what kind of success? Are all types of illustrations equally effective? Illustrations certainly have the potential to aid in understanding complex health websites. People are often drawn to images and they can be used to break up large blocks of text.

But not all users are the same, and it is important to test images with target end users to ensure that the images have the intended effect. The worst case would be to include images that deter people from actually using the website and the information. The best case would be to include images that are universally helpful. While this may not be easy to do, user experience practitioners can work to understand users’ needs and desires. We should consider various ways of including images, such as displaying multiple images that intend to portray similar information in ways that meet different users’ needs. If we work to achieve this goal, we are one step closer to developing effective online health materials that are tailored to the needs of a wide variety of users.

[bluebox]

More reading

Bol, N., Romano Bergstrom, J. C., Smets, E. M. A., Loos, E. F., Strohl, J., Van Weert, J. C. M. (2014). Does web design matter? Examining older adults’ attention to cognitive and affective illustrations on cancer-related website through eye tracking. In C. Stephanidis & M. Antona (Eds.), Universal access in human-computer interaction. Proceedings HCII 2014, Part III, LNCS 8515 (pp. 15-23). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Bol, N., Smets, E. M. A., Eddes, E. H., De Haes, H. C. J. M., Loos, E. F., & Van Weert, J. C. M. (2015). Illustrations enhance older colorectal cancer patients’ website satisfaction and recall of online cancer information. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24(2), 213-223. doi:10.1111/ecc.12283

Meppelink, C. S., & Bol, N. (2015). Exploring the role of health literacy on attention to and recall of text-illustrated health information: An eye-tracking study. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 87-93. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.027

[/bluebox]