A review of

Think Like a UX Researcher: How to Observe Users, Influence Design, and Shape Business Strategy

by David Travis and Philip Hodgson

Publisher: CRC Press 306 pages, 6 chaptersAbout this book

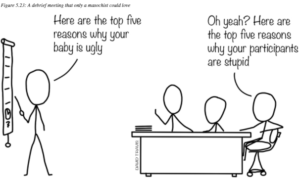

A good reference for Methods/How-To Primary audience: Researchers, designers, and technical roles who are new or have some experience with the topic. Writing style: Humorous/Light, Matter of fact Text density: Mostly text Learn more about our book review guidelines [/greybox] Have you ever had an issue at work that you thought was unique to your company, only to discover that the issue was widespread and had been around for years? Think Like a UX Researcher sets out to assist those of us who could benefit from the decades of knowledge and wisdom that Travis and Hodgson possess. I cannot recommend this book highly enough; it is succinct, comprehensive, and authoritative on the subject of integrating user experience research into the modern business environment. The book covers important topics in corporate user experience research methods: key perspectives that are critical for UX researchers to have, the essentials for getting a UX study up and running as well as analyzing and reporting data, and a discussion on both technical and soft skills that UXers need to have to succeed in their work. This book is recommended for those beginning in the field, but I suspect that individuals who are mid-career will also find useful information, especially if they received on-the-job training rather than in a classroom. After reading the book, an individual should have a good understanding of the skills, tools, and knowledge that are needed to begin or advance in a UX career. They should also come away with an understanding that UX research is as much a science (as Travis and Hodgson point out—it is the science of observing behavior) as it is an art. This career path takes training, rigor, and skill to advance in the field. The first chapter of the book covers what can go wrong with UX research. One of my favorite themes of this book is the insistence that behavior is what matters when making design decisions. Travis and Hodgson discuss what happens when researchers don’t take that edict seriously (bad research and results that cannot be trusted). Rather than fall into these traps, the goal is to employ as much of the scientific method as possible. The remainder of the chapter covers ways to improve the research process, broadly conceived. The second chapter dives deeper into the first phase of user research: planning what sort of research to conduct. This chapter provides the following process to uncover the optimal focus of the research: (1) meet with stakeholders, (2) unpack the root issue, (3) pick the best tool to assess the issue, and (4) start with a pilot study to ensure that you are on the right track. Other topics include the importance of conducting background research on the topic, getting stakeholder buy-in at the start of the project, and recruiting the right kind of participants. Travis and Hodgson also discuss how to properly engage with stakeholders in the early phases of a project, how to write a participant screener, and how to have an early success when starting UX research. The third chapter covers the nuts and bolts of running a user experience study, with an overview of different types of studies, such as ethnography, usability studies, and expert reviews. The fourth chapter discusses how to analyze the results of the study(s), including prompts for enhancing critical thinking when evaluating and analyzing data from studies. It also explores the value of personas, clear usability metrics, and how to construct compelling arguments for making changes when other team members are reluctant. The fifth chapter completes the overview of how to use UX researcher thinking at work, with its focus on how to convince stakeholders that research results should lead to changes. This chapter reviews the importance of thinking of the UX researcher as one member of a larger team with one goal: to improve the product offering. The authors discuss tools such as user journey maps, photo ethnography, affinity diagramming, and SCAMPER. (SCAMPER is an aid in devising solutions and to stimulate creativity; the acronym stands for substitute; combine; adapt; modify, magnify, or minify; put to use; eliminate; and reverse or rearrange.) One of the figures in Chapter 5 that resonated with me and made me laugh was a (somewhat exaggerated) scenario that I have witnessed and been part of more than once. In the figure titled “A debrief meeting that only a masochist could love” (figure 5.23), a stick figure is presenting to a group of other stick figures. The presenter is pointing to a chart with a caption of “Here are the top five reasons why your baby is ugly.” One other figure responds: “Oh yeah? Here are the top five reasons why your participants are stupid.” This scenario provides a humorous example of meetings and projects that can go awry when stakeholders are not properly prepared. This chapter gives some excellent insight into how to avoid these types of situations through the use of UX debrief meetings with stakeholders. As with this chapter and the rest of the book, the authors offer a sense of humor while making a point—something I really like.

The last chapter of the book covers the key knowledge domains of user experience and key details of how to build a career in user research, with pithy insights into how to build a UX team the right way, how to advance in your career (including differences between leaders and managers), and how to gain experience and build a portfolio.

I reviewed an electronic version of the book but plan to purchase a physical copy so that I can refer back to this book easily. The bulleted lists, frameworks for thinking about problems and solutions, and the “Think Like a UX Researcher” questions at the end of each major section ensure that this book will be a useful resource for years to come. Finally, the reason that this book shines is the constant return to the importance of focusing on meeting user needs. The book is written in an accessible manner and should be equally enjoyable for the novice as for the mid-career researcher. If you don’t already own it, do yourself a favor and add it to your library.

[bluebox]

What Does Good UX Research Look Like?

As we’ve reviewed these since, you may have noticed that many of them appear to have a common cause: the root cause is an organizational culture that can’t distinguish good UX research from bad UX research.

Companies say they value great design. But they assume that to do great design they need a rock star designer. But great design doesn’t live inside designers. It lives inside your users’ heads. You get inside your users’ heads by doing good UX research: research that provides actionable and testable insights into users’ needs.

Great design is a symptom. It’s a symptom of a culture that values user centered design. Bad design is a symptom too. It’s a symptom of an organization that can’t distinguish good UX research from bad UX research.

And perhaps that’s the deadliest sin of them all.

THINK LIKE A UX RESEARCHER

Think of a recent project you worked on where UX research failed to deliver the expected business benefits. Were any of the ‘seven sins’ a likely cause? If you could return to the beginning of that project, what would you do differently?

We introduced the notion of ‘information radiators’ in this essay: at a glance summary of UX research findings. Thinking of the last UX research you carried out, how might you present the findings on a single sheet of paper?

We talk about the difficulty of delivering bad news to senior managers. What prevents your organization hearing bad news? How can you help your organization learn from its mistakes?

Every UX researcher has their favorite UX research method, be it a field visit, a usability test or a survey. This becomes a problem when you use the same tool to answer every research question. Identify your favorite and least favorite UX research methods and question if this ‘favoritism’ affects your practice. Identify two research methods you would like to learn more about.

We define a successful UX research study as one that gives us actionable and testable insights into users’ needs. What makes an insight ‘testable’?

[/bluebox]

One of the figures in Chapter 5 that resonated with me and made me laugh was a (somewhat exaggerated) scenario that I have witnessed and been part of more than once. In the figure titled “A debrief meeting that only a masochist could love” (figure 5.23), a stick figure is presenting to a group of other stick figures. The presenter is pointing to a chart with a caption of “Here are the top five reasons why your baby is ugly.” One other figure responds: “Oh yeah? Here are the top five reasons why your participants are stupid.” This scenario provides a humorous example of meetings and projects that can go awry when stakeholders are not properly prepared. This chapter gives some excellent insight into how to avoid these types of situations through the use of UX debrief meetings with stakeholders. As with this chapter and the rest of the book, the authors offer a sense of humor while making a point—something I really like.

The last chapter of the book covers the key knowledge domains of user experience and key details of how to build a career in user research, with pithy insights into how to build a UX team the right way, how to advance in your career (including differences between leaders and managers), and how to gain experience and build a portfolio.

I reviewed an electronic version of the book but plan to purchase a physical copy so that I can refer back to this book easily. The bulleted lists, frameworks for thinking about problems and solutions, and the “Think Like a UX Researcher” questions at the end of each major section ensure that this book will be a useful resource for years to come. Finally, the reason that this book shines is the constant return to the importance of focusing on meeting user needs. The book is written in an accessible manner and should be equally enjoyable for the novice as for the mid-career researcher. If you don’t already own it, do yourself a favor and add it to your library.

[bluebox]

What Does Good UX Research Look Like?

As we’ve reviewed these since, you may have noticed that many of them appear to have a common cause: the root cause is an organizational culture that can’t distinguish good UX research from bad UX research.

Companies say they value great design. But they assume that to do great design they need a rock star designer. But great design doesn’t live inside designers. It lives inside your users’ heads. You get inside your users’ heads by doing good UX research: research that provides actionable and testable insights into users’ needs.

Great design is a symptom. It’s a symptom of a culture that values user centered design. Bad design is a symptom too. It’s a symptom of an organization that can’t distinguish good UX research from bad UX research.

And perhaps that’s the deadliest sin of them all.

THINK LIKE A UX RESEARCHER

Think of a recent project you worked on where UX research failed to deliver the expected business benefits. Were any of the ‘seven sins’ a likely cause? If you could return to the beginning of that project, what would you do differently?

We introduced the notion of ‘information radiators’ in this essay: at a glance summary of UX research findings. Thinking of the last UX research you carried out, how might you present the findings on a single sheet of paper?

We talk about the difficulty of delivering bad news to senior managers. What prevents your organization hearing bad news? How can you help your organization learn from its mistakes?

Every UX researcher has their favorite UX research method, be it a field visit, a usability test or a survey. This becomes a problem when you use the same tool to answer every research question. Identify your favorite and least favorite UX research methods and question if this ‘favoritism’ affects your practice. Identify two research methods you would like to learn more about.

We define a successful UX research study as one that gives us actionable and testable insights into users’ needs. What makes an insight ‘testable’?

[/bluebox]

Jennifer Hunsecker is a Senior Data Scientist at Nielsen Global Media. She's a user advocate, qualitative researcher, and anthropologist. She loves rapid data collection and designing with privacy in mind. Twitter: @jhunsecker