The Tor Project is a U.S. nonprofit composed of individuals from all around the world. Guided by common values such as privacy, anonymity, security, and freedom, these individuals build technologies that shield users from tracking, surveillance, and censorship while using the internet. The Tor Browser is one of the tools developed by the Tor Project that helps people protect their identities. This browser focuses on privacy-first techniques that scrambles all possible information that could be used to pinpoint your exact physical location, making your online activity difficult to trace.

The very nature of Tor’s existence and mission makes it an interesting project for me to study, as their attitude toward privacy goes beyond their competitors, and therefore, their technology and design process takes a different shape. For example, they don’t collect data from users (as all the other browsers do such as Chrome, Edge, Opera, Firefox, Safari, etc.); therefore, all their research initiatives depend on other means that are hard to conduct because its users are people who value privacy and anonymity. To overcome these challenges, the Tor Project has developed research guidelines that respect privacy while ensuring best practices. Additionally, their research is open and accessible to anyone who’s interested—from just reading reports to conducting their own research project.

Study

In 2021, I participated with a grant project from Internews that allowed me to conduct a user research study with Tor Browser. The research proposal was awarded the grant because Tor Browser was interested in conducting user research for their on-boarding desktop experience, but also because the study was located in the Global South, specifically with two feminist organizations in Costa Rica.

I designed the study in three parts as discussed below. The first part was tailored for Tor Browser’s needs, and the other two were out of personal curiosity. The study started with eight participants, but only five ended up finishing the study due to availability and timing. However, these five participants were the same throughout the study.

- Part 1 consisted of an unmoderated test to document any usability problems they had while installing, configuring, and using the Tor Browser (TB). I used a survey at the end of the test to compare their experience to other browsers they have used.

- Part 2 occurred one month after the unmoderated test. A survey was used to understand their browser usage since and if they would recommend the Tor Browser to others.

- Part 3 was a semi-structured interview to expand on why they would or would not recommend TB to others.

Main Takeaways

Participants expected the Tor Browser to behave like any other browser, but to their surprise, it didn’t. From their point of view, the browser created “unnecessary friction” to surf the web; therefore, they didn’t incorporate it into their daily life or as their go-to browser. They only used it when they needed a secure browser experience.

This is relevant to the Tor Project because to maintain the anonymity of its users, they need to have diverse usage of the browser, as that increases the difficulty of tracing who is who. But according to the study, participants chose to use a less secure browser experience for specific reasons. Some of the reasons why participants did this was not because there were errors or the technology did not work, but rather because the technology was designed to work in a specific way that was different than what the participants expected. In essence, participants expected the technology to work in a specific way, but because of how the system was carefully designed to work differently to protect people’s identity, the experience was very different for the participants.

Expectation Mismatch

Before I explain the reasons why participants didn’t choose the Tor Browser in their day-to-day life, it can be helpful to contextualize how the Tor Browser has been grappling with similar issues in the past. This allows for understanding as to the reasons for why the browser’s developers design the way they do and how that design can add to users’ frustration.

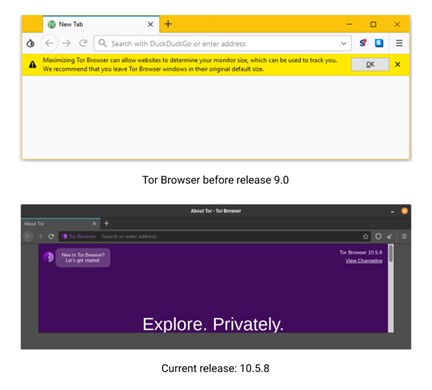

Prior to Release 9.0, Tor Browser (TB) opened with a default window size. If you wanted to maximize or change it, the browser showed a warning advising the user to maintain the default size. This seemingly absurd warning is crucial to stay anonymous as trackers can detect and use your screen size information for identification, but users constantly dismissed the warning. To remedy this expectation mismatch while keeping users anonymous, the TB team incorporated a design that allowed users to change their screen size while also protecting them from trackers. They did this with a feature called letterboxing (see Figure 1) that puts a buffer space around the content of the page to round out the size of the window in multiples of 200 pixels x 100 pixels. By making this change, everyone using TB has predetermined window sizes, not specific screen sizes that could be used for tracking individuals.

Figure 1. Letterboxing allows users to change their window size and still protects them from being tracked.

Alt text for accessibility: Comparison of two Tor Browser releases. One screenshot shows a warning when you change the window size, and the other creates a space between the content and the edge of the browser.

The participants in my study noticed “frictions,” like this letterboxing feature, and perceived them as technical errors or as a lack of features. However, these participant-identified frictions, much like the screen size issue, stem from the built-in technology that is designed to protect user’s data from being tracked.

Speed

When using Tor Browser, the content is displayed in a canvas just like any other browser; however, users get to their sites completely differently. One of TB’s main design differences is that before you can use it, you need to connect to Tor’s Network. Tor’s Network then routes all your traffic through a circuit; the circuit has three nodes that encrypts your data. This clever design choice makes it difficult for your ISP (internet service provider) to know what you are accessing. Instead, your ISP can only “see” that you got routed to the first node, thus hiding where your searches take you after that first node.

This unique browser design can reduce the speed in which the websites load content, as it has to travel to three different nodes before loading to a user’s browser. It also means that before using the internet, a user has to wait to be connected to the network. These inconveniences were identified by several participants: Some said that it was tedious to wait each time to be connected, and others thought their internet connection got slower and tried to troubleshoot it. There were also access errors in which the website would not display its content because the browser was identified as a threat.

History

Other differences were with Tor’s default settings. They are configured in a way that erases history, cookies, usernames, passwords, billing addresses, credit card information, and so on. The focus on privacy makes it difficult for an unauthorized person to view your information, especially if it’s a computer in a public space.

These changes disrupted the participants’ experience and their expectation of how they could use the browser in their day-to-day lives. In one way or another, every participant complained about the effect that these settings created. The most common complaint was that it didn’t store their username and password; therefore, they had to sign in every time they opened the browser. Another one was that by eliminating cookies (and isolating them), websites continuously asked them for their preference, making it frustrating to navigate websites as they constantly were asked for their cookie preferences. And for many of the sites, they were asked every time to complete CAPTCHAs. Finally, some participants were surprised that the browser didn’t remember their history or URLs; for example, a particular habit they mentioned is how they normally typed a couple of words in the URL bar and it showed them the URLs they have visited in the past. These “lack of features” and “technical errors” (as the participants noted) made it impossible for some participants to use TB as their default browser experience as they felt it created a lot of friction to use it.

Content Not Displayed

Tor Browser comes with two plugins (NoScript and HTTPS Everywhere) that prevents malicious code from being downloaded and data tracking. But once again, participants felt some websites didn’t work as expected as sometimes parts of the content didn’t show or behaved entirely different than what they were used to from looking at the same content from other browsers. This unexpected behavior confused the participants: Some thought that the website was acting weird, and others didn’t know how to change the plugin settings. Finally, some participants asked if it was really ill-advised to add a plugin to the browser even though Tor’s FAQ recommended against doing so.

Conclusion

Participants did not use the Tor Browser in their day-to-day life because of the lack of features they normally would expect from a browser (such as history, cookies, usernames, passwords, etc.), their perceived slow internet speed when using it, and the lack of compatibility with their previous experiences with content they normally use. It’s important to note that the issues that participants experienced are consciously designed and crafted in order to protect users. However, because of these issues, they went back to their regular browser and said that they’ll use the Tor Browser when they need to protect their data. But if many users do this, it can jeopardize the health of Tor’s Network and therefore not achieve the goal of the browser—to protect users from tracking, surveillance, and censorship while using the internet.

Tor Project has been facing this tension for years, and they have been innovating and branching out designs like the letterboxing feature, which is a design that compromised more detail of your screen size (although anonymized) for better prevention of being tracked (as users tended to ignore a clear warning of why they should keep the default window size). The people who work on the Tor Project realize that if they don’t alleviate users’ frustrations, people will be less likely to use the browser in their day-to-day life, which is a goal for the project.

The overarching theme observed, not only in this study but also if we look at the historical changes in the Tor Browser, is the expectation mismatch of anticipating a regular browser experience when using the Tor Browser. Because the TB allows you to access the internet in a radically different way when compared to other browsers, there must be changes in how the browser behaves and the user’s experience is affected. But as seen in the study, users don’t understand this underlying difference. Their mental model of a regular browser is retained while using Tor Browser, and as such they discard it as their go-to browser. With this user information in mind, I hope that the people at the Tor Project could use this information to alleviate these users’ frustrations so that in the future people will want to use the Tor Browser as their one access point to the internet.

José Gutiérrez is a UX consultant from Costa Rica. Twitter: @josernitos