Generally speaking, nobody wants to be an enabler of bad behavior.

To enable bad behavior means we are consciously aware of the reality that surrounds us and the impact that the negative has, but be unconsciously accepting of that reality as well. But why are we talking about bad behaviors? Ironically, we as researchers allow bad behaviors to dictate our work all the time. As industry-embedded researchers, we are often compelled to make compromises between decisions that affect the credibility of a study and those that feel best for the business. A common example is when researchers are tasked with designing and executing studies dictated by other processes, such as product development. This often leads to pinched timelines and constrained budgets, which are unreasonable for the due diligence required of credible research processes. In doing this, these two considerations become at odds, viewing them as almost mutually exclusive. This false division can force us to perpetuate bad research behaviors, whether they are workarounds, compensations, or worst practices.

Researchers often lack the words and constructs that help describe how powerful credible research can be for business goals. We have nothing that addresses the mutually exclusive perspective on business and research. There is no obvious, seamless way to bridge the gap between them. Through many experiences in which these gaps were prevalent, twig+fish crafted a framework that not only serves as an effective research-mapping tool but also focuses on the clarity of research value and what it means to a business.

The False Division: A Contributor to Bad Behaviors

Before we get into the framework and how it works, what are some of these observed bad behaviors we speak of? As on-the-ground practitioners and strategists, we are able to identify the source of various bad behaviors and what they look like in practice.

Our field is refreshingly multi-disciplinary, and we pride ourselves in being rooted first in our empathic abilities. Researchers in our field may understand the theoretical foundation of practices and have the ability to plan and execute a study within their business, but may lack the strategic knowledge to envision the long-term potential of research for a business. We have many practitioners in our field who are in essence doing research on auto-pilot—which can leave our industry vulnerable.

In studying people, there are many nuanced variables that influence data, most strikingly, the researcher’s ability to address business goals while remaining credible to qualitative research constructs. Human-centered researchers look for emotions, attitudes, aptitudes, and behaviors.

We are usually looking at these data points for the purpose of some particular end. As an interpretive science, human-centered research relies heavily on the researcher’s abilities to reveal and describe social and psychological phenomena we all take for granted. While many other domains like finance, design, and engineering have clear indicators of skill and credibility, interpretive work has fewer accountable measures of success.

The framework isolates the researcher as a variable impacting the study and makes a case for how the false division can be addressed. Without this framework we can only rely on business constructs (such as time and money) that so often dictate how we do research and determine our metrics of success.

The Bad Research Behaviors

We repeatedly see evidence of bad research behaviors resulting from an imbalanced emphasis on business goals at the expense of research practice. We are guilty of these behaviors, too!

- We lead with method. Familiar methods garner stakeholder support because they offer a predictable process; sometimes we select a method before considering other study variables.

- We believe we can ask people anything. Opportunities to meet with people can be rare and often opens the floodgates to a disorganized, biased, or haphazard set of questions.

- We fail to align stakeholders on the research objective. Without a clear set of research goals that everyone is aligned on, we lead ourselves into the familiar trap of addressing research goals that service no one.

- We expect research to always have a direct return on investment (ROI). An expectation of ROI is sometimes not a viable output of research; sometimes there is a greater benefit of research that is not quantifiable, that impacts the business in an intangible way.

- We understand people based on their relationship with our offering. Existing or potential customers are the obvious subjects of research, which means we lack exposure to a deeper understanding of all people, or human behavior, generally.

- We allow external variables to dictate our study designs. Whether it is repeated removal of research processes due to lack of time or end-of-year budgets, we relinquish good decision-making in favor of other processes (like design or development).

- We expect research to answer everything. We rely heavily on research to answer questions that might have other or better answer sources.

- We do not advocate for good research. Even when we become aware of bad behaviors, we allow them to continue in our businesses, sometimes creating workarounds that get the work done but at the expense of credibility.

These are just a few examples of realities that might exist within research and how it is juxtaposed in the business world. Though some businesses avoid these pitfalls and contribute to an industry-wide good, the reality is that many do not. We have seen both the good and bad behaviors, but no infrastructure to avoid succumbing to the pitfalls. The need for a framework focused on designing credible research studies, and also one that reveals the total landscape of research’s power potential, quickly became evident.

The Framework

The framework exposes tendencies of cross-functional teams that can amplify the divide between research and business. The first: What will the research do for the business? The second: What are considerations feeding into the study?

Research in industry rarely operates in a vacuum; it is always part of an agenda. As such, research output must be serviceable or actionable to the business. We consider the outcomes of research in terms of helping others do work: Will it be used to inspire creative, solution-oriented teams, or will it be used to inform tactical decisions.

Example:

INSPIRE – An e-commerce website design team needs to understand why people buy things (anything).

INFORM – Determining if the “Add to Cart” button on the redesigned website is well positioned.

Research in industry also has a number of disparate inputs and realities. The level of wiggle room of these inputs is another consideration in aligning business and research goals. If the inputs are more flexible, then fewer assumptions and constraints are introduced into the study. When more assumptions and constraints must remain true, then inputs are more fixed.

Example:

FLEXIBLE – We want to extend our offerings beyond our core product to something else.

FIXED – We know that we are developing a new website.

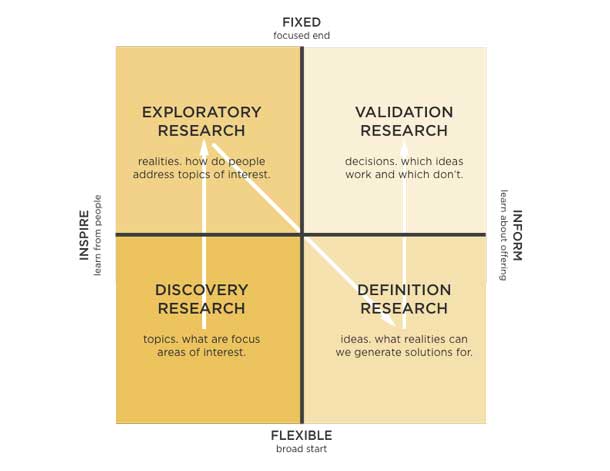

These four end-points form the framework in a simple two-by-two (see Figure 1).

Once stakeholders are aligned on the definitions of each spectrum, we then ask them to write down any and all research questions. We keep this request open so that they can capture exactly how they might ask the question without any influence. Each question is written on a single Post-It and then placed on the map. We work with the stakeholders to place their questions so we can begin a conversation about where they fit. This initial conversation is another key step in alignment.

What The Framework Reveals

Each quadrant has a research process associated with it. Different patterns emerge in this initial placement of questions. A typical result has questions all over the place, sometimes signaling misalignment. Another result is that all questions fall on the Inform side, which is also typical for businesses where human-centered research is embedded in a constant state of tactically answering questions with tight product scope. Questions are rarely in one quadrant—that signals alignment or a very closed perspective on the potential of research. Even more rarely do we see all questions on the Inspire side.

Taking a moment to reflect on question placement helps begin a discussion around the business tendencies, priorities, and expectations of research. The discussion is incredibly important in alignment. From there, we discuss each quadrant’s purpose.

Quadrant Descriptions

| Quadrant | Representation | Process | Example |

| Discovery Research

|

Inspire/Flexible

|

Gathering stories for deeper understanding to identify promising focus areas or opportunity spaces.

|

What is it like to live with diabetes?

|

| Exploratory Research

|

Inspire/Fixed | Honing in on a focus area to bring further description or clarity to the experience or lived reality. | What are the meaningful characteristics of an ideal diabetes management tool?

|

| Definition Research | Inform/Flexible

|

Expanding on experiences and lived realities to reveal solution themes, concepts, or ideas. | What are different ways to create a better, more meaningful diabetes management tool?

|

| Validation Research

|

Inform/Fixed

|

Vetting the solution themes, concepts, or ideas to make improvements and measure changes.

|

What works and what does not work in our diabetes management smartphone app?

|

What you might notice in Figure 2 is that there is a natural progression between quadrants beginning with Discovery and ending with Validation. Our claim is that following the path (the letter “N”) ensures that the full potential of research can be intentionally leveraged. We do all of this by staying true to the scope of each quadrant and its purpose. In doing so, we bolster our credibility as researchers while at the same time demonstrating alignment with business goals. Even more important is the team involvement in sharing all their questions and reflecting on what types of questions they tend to ask as a team and as an organization. The framework serves to create a research roadmap as well as a reflection tool on business research realities. Capturing any group reflections and assumptions helps reveal tendencies the internal team might have that can influence research practices.

How This Framework Can Address Bad Behaviors

As researchers, our goal is to focus on the human element and how it is positioned in any solution. We were able to raise a number of bad behaviors earlier that might resonate, and using this framework, can address process gaps that lead to bad behaviors.

With the framework applied:

- Method is not the driver anymore. Specific methods flourish in specific quadrants. After all, what is a focus group? What is an interview? The methods themselves cause confusion since there is no one “clear” interpretation for what we call a method.

- Questions are now organized into the quadrants. This leads to a more strategic approach to study design, one that maps to a larger story arc of research’s power potential. Research studies that cover more than one quadrant of questions are done so with intent and by design. The scope of the project and its outputs are clearly defined.

- Hidden agendas are exposed by copious documentation of all questions; interpretations and misalignments cease to exist in someone’s head because they must be written down. Decisions are public and everyone has to align on semantics.

- There are times to ask people for nuanced realities and there are times to ask them if something just works or not. Those lines are drawn clearly and with intention, avoiding confusion.

- The lack of a certain type of research (and therefore, set of questions) is revealed, exposing weaknesses in business processes and gaps that can be addressed.

- There is a greater understanding and appreciation for when customer insight is needed and when there is a need to be inspired by greater human behavior.

- The output of each quadrant is no longer a surprise and can be tempered appropriately to expose the value of the research and the researcher.

- Advocating for research and staying organized becomes attainable because there are implementation rules around each quadrant that are visibly understood by all team members

Each study is an opportunity to further support and communicate the power and potential of human-centered research. An added benefit is the recognition of how questions must be asked in order to yield the required output. Open discussion of this results in more empathy toward the team actually conducting the research. Contributors can appropriately home in on the intent of their questions without misinterpretation of what the question yields.

This framework is one of many tools that can be used to demonstrate the strategic contribution of our domain, while enabling researchers to design credible studies.