Note: This is a two-part article. Part Two will appear in our next 19.1 issue.

Our news feeds today are rife with ethical issues as they relate to the ever-increasing technologies we use. Self-driving vehicles with automated safety features, social media privacy issues, addictive techniques used in apps, and persuasive design methods all affect user experience as a profession. Yet there has been little written to compile and categorize the different ethical issues within UX design. How far-reaching and how many types of ethical issues are we facing as professionals today?

The types and nature of ethical issues in our profession will, of course, continue to shift and grow as more technology is developed. As with any discussion concerning ethics, the answers will be murky at best and often unanswerable. But the purpose of this article is to begin the development of an ethics taxonomy. It would serve as the foundation for a framework to aid designers in evaluating concepts, while also underscoring the importance and impact of ethical issues in design today.

The Three Categories of UX Design Ethics

Ethics within UX design can be divided into three primary categories:

Existential Values: This is central to our existence as designers and what our values are in relation to what we create. These issues are more rooted in the self, but are perhaps the first we should consider in our pursuit of ethical design.

Ill or Misdirected Intent: Where the intent is to place the user’s needs below some other need or goal, resulting in a product or service where ethics will likely become a concern. Sometimes it is not that the user’s needs were secondary; rather, there was an attempt to balance user needs with business needs, for example.

Benevolent Intent: This is the ideal state we should strive for where the intent is to place the user’s needs first. We are user experience designers with a charge to place users’ needs above all, while still approaching product development as pragmatically as possible. Despite having the best of intentions, however, latent ethical issues can still arise.

Existential Values in UX Design

Existential values are beyond a particular product or feature within a design. They sit higher in the hierarchy of ethics. For instance, who do you work for? Do you agree with the company’s values, the mission and design intent of the products and services the company produces? An example: Would you work for a company that produces products or services designed to harm people such as the tobacco, firearms, or alcohol industries?

Granted, most designers are not forced to make such extreme or binary decisions regarding the ethics and intent of the organizations they choose for employment. However, even industries such as healthcare must make a profit, and often do so as a result of human misfortune. The industry or organization you work for, its mission and values, serve as a filter through which all of the ethical issues below will likely pass.

What are your values as a designer and where would you draw the line? Would you work on the interface of a cruise missile, knowing the weapon could result in the deaths of many? Would you have worked for Hugo Boss, manufacturing uniforms for top-ranking Nazis? Would either of these scenarios be worse than working for a social networking company responsible for fake news? These are questions a designer must ask themselves in relation to their own values.

We exist, as designers, to create products that are easy to use and typically make the world a better place. But do we always do that? Do we not sometimes create products that cause harm, or design for organizations that cause harm? When addressing ethics, first and foremost, we must define and address our own system of values.

A Question of Intent

Any discussion of ethics in UX design must consider the user in relation to our intent. As Jared Spool has famously said, design is the rendering of intent. “The designer imagines an outcome and puts forth activities to make that outcome real.” Our intentions influence the design and subsequent outcomes or consequences. We can have good intentions, ill intentions, or misdirected intentions.

In defense of designers, we must consider these ethical issues holistically. As controversial as it may seem (and was at the time), Spool also stated, “Anyone who influences what the design becomes is the designer. This includes developers, PMs, even corporate legal. All are the designers.”

As a designer working in healthcare UX, I have found this statement to be generally true. The design of a product or service is often not rendered as I originally intended, having been influenced by other teams. My intention was noble. But, my lack of control over the design process led to a misdirection of my intent when other teams, values, or requirements interceded prior to the release of a product.

This holistic aspect of design is important. Ethical issues often fall beyond our control as designers. Our intent is often shaped or diverted by teams and individuals who do not bear the title of designer, nor have the word “designer” anywhere in their job description. They often have a different intent and end-goal than the designer or design team.

Intent is a controversial topic in ethics. The road to hell, as they say, is paved with good intentions. For the purposes of this article, we will not debate intent. Rather, we will use it as a delineating marker between ethical categories—those with ill or misdirected intent and those with benevolent intent. Part Two of this article, which will be available in issue 19.1, will cover the latter.

Ill or Misdirected Intent

Placing the business needs first or attempting to balance business needs with the user’s needs is primarily where good design intent is derailed. An organization’s business is not to serve the business, but the user (or customer). When organizations place the business first, the intent of the design is compromised, as is the user experience. Almost all ethical issues we see in this category arise as a result of an organization’s desire to generate commerce or pursue some goal other than to serve the user.

As designers, we have to be aware of competing needs. Organizations do have to turn a profit and we must be pragmatic in considering business needs, regulations, and how the ecosystem influences the design. However, when such situations exploit a user, cause harm, or result in a difficult product to use, we have crossed a line as designers.

The following ethical issues represent situations where the design is clearly of ill intent.

Dark Patterns

These are patterns deliberately designed to trick the user into purchasing or providing information (e.g., an email address) they did not intend to. Sneaking items into your shopping cart, adding additional charges at the final step in a checkout process, and tricking a user into unwittingly sharing private information are just a few examples. There are a number of these patterns featured on darkpatterns.org, and they are clearly unethical design methods. Moreover, the majority of them are financially driven.

Selling What Is Not Needed

Ancillary products and services are a division in this category. This is where the customer is offered items to supplement an item they are purchasing. Or, perhaps they are offered an upgrade for an additional cost. One could make the case that ancillary products and services are mutually beneficial for the customer and the business. Indeed, when done well, they can be. However, they are often unnecessary or completely unrelated to the product or service being purchased and clearly benefit the business more than the user.

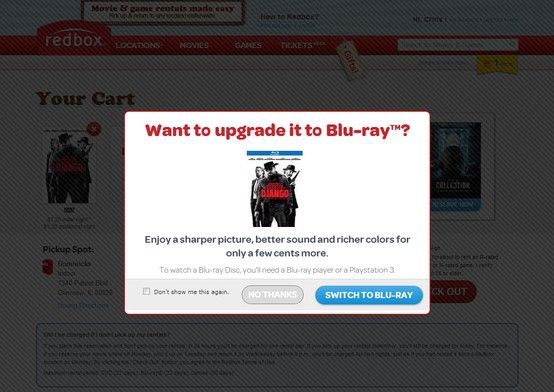

Ancillary products are often lumped in at the end of a sale and usually are not pertinent (thus violating the very definition of ancillary). Redbox does this during the checkout process (Figure 2) when they ask if you would like to upgrade from DVD to Blu-ray, which is 50 cents more. Their analytics are either non-existent or incorrect because despite having not owned a Blu-ray player in years, I am asked this consistently when renting a video. So the question is not only annoying to a user, it forces them to manage an extra interface control on the off-chance Redbox could make a higher profit.

Distractions to Drive Commerce

Advertisements, or what I refer to as unnecessary distractions, also fall within the realm of placing the business before the user. Yes, a business must profit and create revenue in order to continue operations. But pop-ups, auto-play videos, and advertisements a user must navigate around are distractions clearly designed with the business, not the user experience, as a primary intent.

Beyond the web and advertisements, there exists a concept known as “alert fatigue.” This is often seen in healthcare interfaces where the intention is not always noble. The alerts are sometimes designed to prevent patient harm (a noble intent). However, many times the alerts are in place to ensure organizational policies or documentation are enforced for higher profits (a less than noble intention). The distractions can cause harm when a user’s attention is directed from a higher priority situation. An even greater problem is the unintended consequence of inducing fatigue from the sheer number of alerts in a given system.

Transparency

A lack of transparency—where companies purposefully hide information or make comparisons difficult—is another ethical issue. It can technically be considered a dark pattern depending on how it is used. Case in point: Product pricing by region has been reported in the media in recent years. For example, in the United States, an online retailer may charge a higher price for a pair of shoes in Chicago, Illinois, than in Louisville, Kentucky. Other examples include software updates with unintended consequences, such as slowing phone performance, or platform updates where privacy terms are changed and users are unaware their private information will be made public. It is unclear whether the latter instances drive commerce or are simply latent ethical issues. But it is easy to see how such issues are beneficial for businesses and not users.

Metrics

Using metrics incorrectly or unethically to drive traffic (and thus commerce) and behavior is the final ethical issue where ill or misdirected intent exists. Simply showing analytics to a user (such as the number of “likes” a post has received) drives behavior, engagement, and traffic. This in turn drives commerce and has an addictive effect on the user, much like a slot machine. Design ethicist Tristan Harris has discussed this topic in his TED talks.

Wearables (e.g., smart watches) that report inaccurate metrics can drive behavior, such as overeating when we believe we have burned more calories than we truly have. We buy these devices assuming accuracy in metrics (which is partly why they sell so well). As the research of behavior scientist B. J. Fogg indicates, computers and technology are perceived as authoritative by humans. Because of their precise nature, we lend a certain amount of credence to the information they present.

Metrics such as analytics can also be used irresponsibly to give content greater exposure, as evidenced in the multiple “fake news” scandals following the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The ethics of how analytics are analyzed and subsequently used to drive traffic (i.e., Black Hat SEO) could encompass an entire book. It is beyond the scope of this article, but metric use primarily revolves more around business needs than customer or user needs.

Conclusion

Understanding the different types of ethical issues designers face is the first step in building an ethical framework for the UX profession. This framework can help guide design teams and organizations in the development of products where harm, exploitation, and deception are minimized or non-existent. It can also serve as a foundation for a code of ethics—a code that will guide us in how we choose and approach design projects, as well as how we decide who to work for and what our personal values are.

Part One of this article has been devoted to exploring existential values and those ethical issues where ill or misdirected intent occurs. In Part Two of this article, we will identify and examine ethical issues where the intent is benevolent, but results in latent ethical problems.