I always pictured that, upon graduating, I would land in the technology sector at a Fortune 500 company or at a startup working on the next big app. Instead, I found myself working as a visual designer in recruitment for Alzheimer’s research studies.

As a result, I’ve run into several unfamiliar situations that require recall of subject matter that had been neglected in my curriculum and educational experience. Although the fundamentals remained true, my work experience had to fill in certain knowledge areas so I could perform my job effectively. This article discusses my lessons learned about the following:

- Readability

- Timelines

- Target Audience

- Messaging

The conflict that I frequently had with these knowledge areas was that the approach taken to them in the university differs from how they function outside of it. As students learning about the topics of design, technology, and messaging, we would think and talk about consumer enterprises like the Apple’s and Tesla’s of the world. This makes sense because these are some of the biggest companies in the world, and everyone has a reference for them. But their goals, and tactics to achieve their goals, are much different than the work I’ve found myself doing. The healthcare field, topics like research, and how to talk about them are left to biology majors and those who want to be scientists. (You generally don’t run into people in a web design class who dream of working in healthcare). Now, working in the intersection between two fields, I’ve found myself doing just as much learning about the science field as I do about the field of design.

Auxiliary to this pain point is the issue of audience. Working in the field of Alzheimer’s, I’ve had to finetune my knowledge through experience of very specific and niche audiences like the above-mentioned scientific community as well as elderly populations that I didn’t have much, if any, exposure to in my formal education. I’ve noticed this same adjustment taking place in real time when working with vendors new to the field of healthcare.

During our educational years, which blur together for most students, we build our base of knowledge through the experience of others using lectures from our professors, assigned readings from textbooks, and instructional videos from various sources. We imprint these into our brains through various means, be it study sessions, tests, or essays. The closest thing students get to real-world experience is usually projects that attempt to mimic it. In our professional lives, the paradigm shifts to learning on the job. This type of learning, the gritty kind that doesn’t come with a degree, is vital to our growth as professionals. Perhaps this is why internships, and often multiple internships, have become almost a prerequisite to finding a job in today’s marketplace. Since I’ve gone through the process of being hired for my first job as a professional and am surrounded by peers of the same experience, it has been strange to see individuals who have gone straight to their master’s program having a harder time finding a job than those who opted for internships and entry-level roles. I think this speaks to the importance of experience-based knowledge.

Although we still read books and articles or take courses to enhance and refresh our skills once in the workplace, either for professional development or to keep our skills up to par with the rapidly advancing technological landscape, this information only becomes useful to us when we put it into practice in our professions. The bulk of learning in our careers, aside from seniority and institutional knowledge, comes through experience and problem solving when we encounter new challenges. This is why we expect to learn more in our later years than when we are newly out of school. Our experience builds, and we learn things that can’t be taught in a classroom.

The problem that exists with learning through experience is that, for most of us, we take for granted the subtle teachings of trial and error and treat the information learned as a commonly understood truth or universal fact. We don’t note our day-to-day lessons. Even small challenges, such as how to work the company printer, might make us think, “Thankfully, I figured that out before anyone saw me struggling,” rather than wondering if anyone else has had that same issue.

The elephant in the room is that the small lessons, the ones we often take for granted, are actually instrumental in our ability to perform our job. Incorporating these lessons becomes second nature. Think back to your first job: While you were overwhelmed, perhaps your coworkers seemed to know exactly what to do and when to do it. There’s even a good chance they hadn’t recognized this ability in themselves.

In the following sections, I will recount a few of the lessons that I have learned working day-to-day in the intersection of design and healthcare. I hope these lessons afford you some new information, things to think about, and an opportunity to reflect on your own professional growth and learning.

Readability

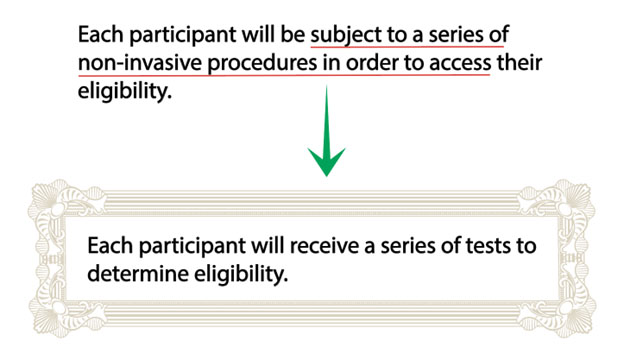

What is readability? Sure, we’re all aware that not everyone can read or even read well; if you’re reading this right now, congratulations on being one of the lucky ones. But what if the words before you were to suddenly turn to an in-depth discussion of the merits of PET scans, Amyloid-β Oligomers, and blood transfusions? We all have different bases of knowledge, and reading levels vary drastically. The issue with this is that, unlike the consumer field in which audiences can be very broad and topics can be spoken about in very general terms, healthcare topics are often new to audiences and can be immensely complex. Added to this, it is essential that inclusivity and diversity are at the forefront of everything, and so these complex topics need to be understandable to everyone. How can one expect a treatment to work for everyone otherwise? Figure 1 illustrates how readability affects written content for the public.

Timelines

Let’s dive a little deeper into timelines. The biggest difference I’ve encountered in this area is the stakeholders involved. Due to the delicate and intensive nature of healthcare, there are far more considerations for the copy and design of public-facing materials and websites than for consumer businesses. This can lead to bottlenecks in the linear process of a project and cause timelines to be pushed back.

In recognition of the complex nature of the healthcare field, approval processes for materials can be lengthy and include many working groups of stakeholders as well as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) explains IRBs as “an appropriately constituted group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects… The purpose of IRB review is to assure, both in advance and by periodic review, that appropriate steps are taken to protect the rights and welfare of humans participating as subjects in the research.”

IRBs vary in their structure from institution to institution, and timelines for their processes and review can vary accordingly. What’s important to note about them is that for content to be finalized, it must pass muster. This process can take multiple weeks and require additional effort if the content must move through multiple rounds of approval.

When designers work with external groups to create designs and content, competing timelines can conflict and add an extra two to three weeks; this can cost money and disrupt timelines. Further, the added difficulty of persuading health professionals and investigators to commit time from their packed schedules to review materials beforehand can also cause further delay.

Target Audience

This next consideration is perhaps the trickiest; it has received more recognition within the design field in recent times. In Alzheimer’s research and often in the healthcare field, the target demographic is often a vulnerable population, the elderly.

The first step in my design process has always been to view everything through the lens of the audience and ask myself, “Who is this content for?” What if the audience has little or no familiarity with technology and the internet? You can imagine many considerations: making navigation as simple and concise as possible, making sure webpage objects such as buttons are unmistakably interactive, avoiding flashy page elements that may be confusing, and so on. Every step of the design process must be deliberate and take into consideration the unique needs of the population in addition to the general public.

The most impactful lesson learned working with this audience is that one’s own sense of familiarity can be misleading. I must remember to inspect my work through the perspective of someone who is 60, 70, or 80 years old, instead of 23. For example, this audience neither wants nor needs non-essential information; many just prefer to keep it simple. It can be tempting to design fancy animations and bold design schemes, but to get the content across, it’s best to put embellishment aside and prioritize the message in its purest form and format. This ensures the audience can digest the information rather than be overwhelmed by it.

Messaging

Messaging is where I have encountered the biggest discrepancy between my education and my professional experience working in UX and the Alzheimer’s field. In class, projects tend to focus on consumer examples sourced from companies like Apple and Microsoft according to the consumers they actively market to.

In medical research, the goal is not selling anything, but rather asking for time. For a practitioner, shifting mindset to reflect this reality when designing or writing copy can be a difficult transition because you must drop your go-to approaches and appeal to something beyond the surface level within the audience. Luckily, this population’s motivations run much deeper than owning the newest watch or buying the latest technology. I have found that when the ultimate goal is not monetary but altruistic, and the aim is to help, the audience is more willing to spend time. Personally, I also find that the work can be much more rewarding.

Final Thoughts

Although challenging, designing within the healthcare field offers reward in its purest form through helping people. Practitioners face new challenges each day and from them personal growth arises that cannot be gained elsewhere. If you’re as lucky as I am, you’ll get to apply this knowledge to advance the work you and your colleagues do.

Perhaps lessons learned in my early career have stirred within you an appreciation for all that you have unconsciously absorbed throughout your own career. Hopefully this discussion on the knowledge areas of readability, timelines, target audience, and messaging has offered some valuable insights you can apply to your own work.

Further Reading

The Power of Empathy—Dr Brené Brown on Empathy vs Sympathy (2013)

Inclusive Design: 12 Ways to Design for Everyone

Working with Older Adults (American Psychological Association)

Brendon Smith is a young professional visual and UX designer with a passion for design. He currently works for the Keck School of Medicine Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute in addition to freelancing for a variety of web and graphic design projects.