Having the largest population in the world is often viewed as one of the biggest advantages for Chinese technology entrepreneurs, but it also presents many challenges. How do you stand out in such a large crowd and how do you attract users and followers? One of the top priorities for Chinese internet companies is to push growth and to strive for ascendancy both locally and globally.

Chinese companies have a hunger for new users, but growing a user base in China can be a brutal business. That was my main takeaway from a research visit to Taobao seven years ago. Taobao is an online shopping and auction service similar to eBay. It helps ordinary people sell merchandise online. It contributed to the early market success of Alibaba Group, which had the biggest IPO ever on Wall Street. On the day of my visit, a user protest was going on outside of the corporate Taobao headquarters in a busy shopping district in Hangzhou—the ecommerce capital of China. The team was hard at work in the usability lab, but it was difficult to ignore the cries of anger from protesters who had gathered outside the building. The protest was triggered by an update made to the Taobao search ranking algorithms a few days before. Dozens of online merchants from the local area were demanding that the company revert back to their previous algorithms. The merchants were among the early adopters of the Taobao service and they helped fuel the company’s success. However, as the e-commerce platform evolved and the marketplace grew, more and more merchants joined. The early adopters saw their user traffic decrease as new merchants were added. Their frustration grew as their visibility diminished. The prosperity of their online shops was primarily determined by the logic of the search ranking algorithms, but those algorithms were regularly tweaked by Taobao, a common practice for many internet companies including Facebook and Google.

That day’s usability test was clouded in an atmosphere of user displeasure. When the test participants used the newly introduced filtering measures to make choices about women’s sandals, the observers behind the two-way mirrors exchanged quick comments in low voices. Everyone involved felt the responsibility and pressure to deliver accurate and fair search results. The protesters had reminded the researchers that the decisions made in the lab had a direct impact on the lives and the fortunes of their users. The empathy that the researchers felt toward the online shop owners also came from their own experiences. As employees of Taobao, they understood how difficult it was to attract new users in a very crowded field. It was an uphill battle for Taobao to beat eBay and other competitors and to ascend to the top of the pack. In my hometown, where Alibaba is headquartered, stories still circulate about how Jack Ma, chairman of Alibaba, was treated as a jokester when he first introduced his e-commerce concept at the beginning of this century.

Mixed feelings often wash over me when I study how Chinese startups and high-tech companies interact with their users in this globalized world. There aren’t always protesters reminding us of the impact of our decisions. In this article, I examine how Chinese technology companies approach growth hacking and how they promote user communities in the context of global UX innovation.

What is Growth Hacking?

Growth hacking refers to the approach of utilizing alternative methods outside of traditional marketing campaigns to acquire, activate, and retain users. Building on the viral features of digital communication technologies, these non-traditional methods tend to be less expensive and more grassroots—this is where the word “hacking” came from.

This term was coined by Sean Ellis and is based on his early experiences helping startup companies in Silicon Valley grow their user bases. To acquire new customers for Dropbox, Ellis and his colleagues introduced a referral program to reward users with extra storage space when their friends signed on as new users to the service. Because storage space is a core value of the product, providing additional storage space served well as a key incentive for existing customers. Therefore, existing customers were highly motivated to refer friends, participating in the collective effort of pushing growth for Dropbox. Growth hacking has also contributed to the successes of Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and other winning startups. Nowadays a “Growth Department” is a must-have for high-tech companies.

Growth hacking integrates methodologies and toolsets from marketing, product design, and UX to drive the growth of the customer base, to scale the product, and thus to expand the business. Based on user data analytics, companies can respond to emerging user trends and interaction patterns in a timely manner. Using an agile design cycle, they can quickly update products.

In one of his recent interviews, Ellis shared that “one of the biggest levers for a growth hacker is improving the user experience”. Indeed, a product with poor UX will be hard to build, grow, and will not retain its user base. User experience is an integral part of growth hacking. Growth hacking starts with data analytics to identify user behaviors and habits. It often involves mobilizing users to determine the best fit between product benefits and user values. As a matter of fact, companies should push for growth soon after they identify the core values of a product and align them with the existing user base. Otherwise, the development effort might be a waste of money.

Growth Strategy in China

A growth strategy involves converting visitors into users, which is essential for Chinese startups. The growth strategy used to fuel the engine of the Chinese internet economy is called YunYing. It refers to the intervention mechanisms that help connect products and users, including methods of DiTui (offline strategies of promotion and growth) and WangTui (online strategies of promotion and growth).

In the early stages of the Chinese internet economy, the growth strategy of many companies was focused on encouraging user traffic. The competition at that time was not intense. Existing online users did not have many destinations to choose from and there were many unexplored user markets to tap into. Therefore, getting the user traffic almost equated to acquiring users. As a result, the growth strategies focused on capturing the consumers’ attention. The strategies tended to be simple and direct, usually converted from traditional marketing methods. Figures 1 and 2 show the offline growth events for the Baidu Baike, an online encyclopedia service developed by Baidu (China’s Google). Two methods were used to attract online traffic: first, a group of female marketers performed cheerleading dances at a busy subway station in Beijing to publicize the service (Figure 1). Second, thousands of cards with QR codes were attached to the plants in the Beijing Botanical Garden (Figure 2). Visitors could scan the codes to learn more about the plants from the online encyclopedia.

As competition became more intense, more sophisticated strategies were developed to utilize data analytics and build more targeted connections between the products and users. While the organic link between product design and growth strategy was not established at an earlier stage of growth development in China, more companies saw the power of integrating and synchronizing the two processes of product design and growth. For example, to retain users, an app that provided online family doctor consultations introduced health-related tracking features (for example, activity tracking and menstrual tracking). The rationale behind the addition of the new features was that activity tracking would keep the users engaged on a daily basis, and that the need for menstrual tracking would occur more frequently than the need for a physician consultation. As a result, the new features increased the stickiness of the app and encouraged users to return more often. Other popular methods of acquiring and retaining users were also adopted. For example, the companies developed and nurtured user communities which turned early adopters into product fans and evangelists. Focusing on the booming fan economy in China was a strategy employed by Chinese cell phone manufacturer XiaoMi and Huawei. This strategy was covered in an article published by UXPA last September .

Chinese growth strategies continued to evolve. In the past few years, some companies have begun including American growth hacking methods, such as the pirate metrics of AARRR (acquisition, activation, retention, referral, and revenue) into their toolsets.

Weibo: A Chinese Case of Growth Development

For Chinese growth strategists, the core value of YunYing lies in connecting products with users so that products resonate. Strategists often work in three areas: presenting the product’s unique values and benefits to the user, creating new and innovative ways of using the product, and building a network and ecosystem around the product. Through this process, ordinary consumers are converted into informed and motivated users who connect with the values of the product and support the mission of the business.

“Weibo” is the Chinese translation for “microblogging.” Wei stands for micro and bo for blogging. Launched in 2009 after Twitter was blocked in China, it is often regarded as a Chinese copycat in the Western world. However, it outgrew Twitter as a Wall Street winner last year, and its market capitalization surpassed Twitter’s in February 2017.

In a 2013 article that I wrote for IJSKD, I traced Weibo’s early development and came to the conclusion that Weibo was a local variation of a globally diffusing technology (for instance, microblogging in this case). Weibo stood out from many other Chinese copycats of Twitter because it successfully adopted a social media service into a Chinese context with features originating from the Chinese internet culture, such as rich media, threaded comments, Wei-group, Wei-event, and so on. Some of these features found their way back to later versions of Twitter. For example, Weibo users were able to embed content, such as pictures, videos, and audios early after the product launch, but Twitter did not introduce this feature until October 2013.

The rich-media format inspired new ways of using Weibo. One popular method involved presenting large chunks of text in an image embedded in a post. This allowed users to get around the 140-character limit. In the summer of 2013, an emerging novelist named Zhang Jiajia used this approach to share a series of novellas. He tagged his post with the hashtag “bedtime story.” His novellas became such a big hit that his Weibo posts were retweeted more than 1.5 million times and read by 400 million users. His novellas were eventually published in a book that became a bestseller. One of his novellas was even made into a blockbuster movie.

As a local uptake of a global technology assemblage, the success of Weibo represents a new trend of global technology design, development, and diffusion. To see a recent example, look at Facebook Messenger. The design of the interface and its features was influenced by popular East Asian mobile chat apps like WeChat and LINE, as well as Western social media apps like Snapchat and Instagram.

Guiding User Participation

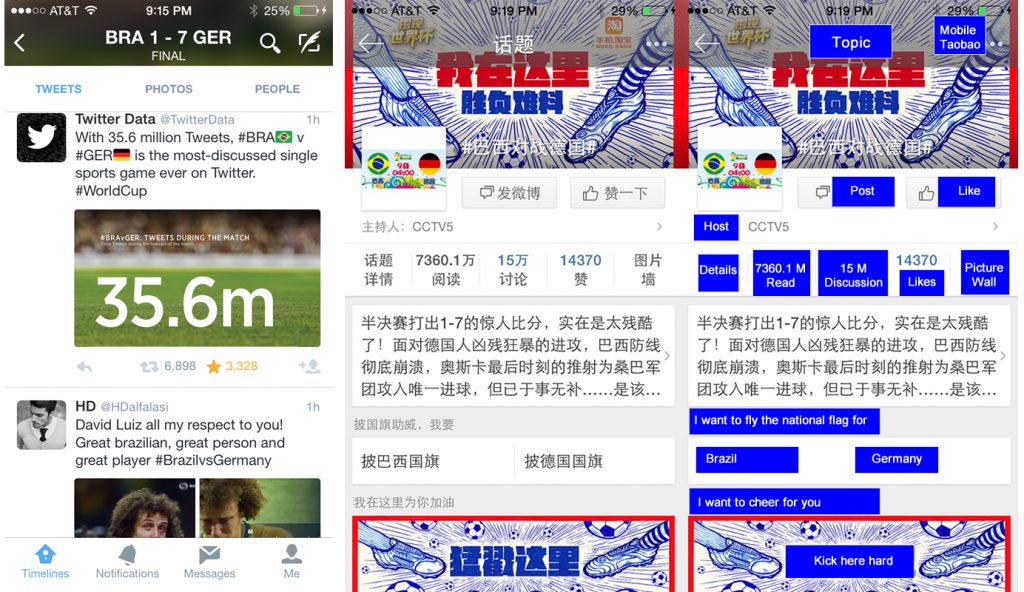

Content editors play an important role in the Chinese growth strategy. They bridge the gap between users and products and help to scale up acquisition. Content editors are vigilant about monitoring internet trends and the culture of everyday discourse. They seek out opportunities to push content, initiate participation, curate user-generated content, and guide user participation. These activities support product growth. During the 2014 FIFA World Cup season, Weibo created many Wei-event pages to attract visitors—Chinese people are obsessed with soccer in the same way that some Americans are obsessed with baseball. Figure 3 compares the mobile interface of Twitter and Weibo captured six hours after the legendary soccer game between Germany and Brazil. This game was the most-discussed single sports event on Twitter at the time. During the event, Twitter used a machine algorithm to curate related tweets. The algorithm created simple categories to organize tweets, photos, and people.

In contrast, Weibo delivered a Wei-event page. Weibo also partnered with a popular Chinese sports channel to promote the event through traditional media channels. Weibo provided five tabs to encourage user participation: discussion, number of reads, number of discussions, number of likes, and picture wall. Weibo used labels that were helpful to infrequent site visitors who might be unfamiliar with the microblogging service and who were drawn to the site because of traditional marketing associated with the sports event: they used HuaTi (topics) and TaoLun (discussion) instead of Weibo (microblog), in comparison with tweets used on the Twitter page. For regular users, the Wei-event page highlighted several ways to participate (for example, buying lottery tickets, uploading photos, and accessing other curated pages for other FIFA games). The site delivered quality media content in a timely manner and provided a user-friendly interface with a structured means by which to incorporate user content. By showing potential users different innovative ways of using the product, Weibo encouraged greater user participation and inspired more user-generated content.

Nurturing New User Communities to Overcome Growth Stall

Soon after it dominated the microblogging market in China, Weibo faced two challenges: the increasing cost of self-censorship under the heightened control of mainland China, and the quick rise of WeChat, a popular Chinese mobile messaging and social networking app. The latter provided the biggest blow to Weibo. Many Weibo users migrated to WeChat for their social networking needs. According to the CNNIC (China Internet Network Information Center), Weibo’s usage rate by Chinese Internet users dropped from 54.7% to 33.5% between 2012 and 2015.

Weibo chose to refine its core values and move in the direction of social media marketing (some earlier movement of this shift was noted in the 2013 IJSKD article). The new vision included:

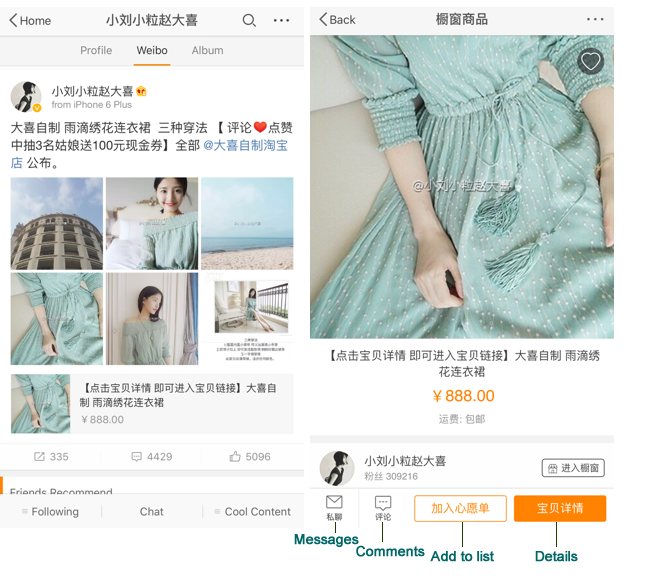

Feature redesign: Weibo partnered with Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba in 2013 and redesigned its timeline interface. The new Weibo-Taobao interface promoted Taobao products. The product timeline consisting of price, product popularity, and a “Buy” button. Later, a nine-grid structure was introduced. The grid made it easier to promote Taobao products by allowing merchants to provide nine eye-catching images in a structured format. Figure 4 shows a Weibo product post produced by a 24-year-old apparel designer. The designer started her Taobao business while still a college student. She is now an internet celebrity with more than 1 million followers. When she released her new line of products on Weibo, her entire inventory of merchandise (5,000 pieces) sold out within two seconds. Nowadays, Taobao merchants don’t need to solely rely on Taobao’s search algorithms for traffic like the protesters I saw years ago.

Community growth: Weibo facilitated the creation of new user communities by focusing on a better-defined user niche. It updated its recommendation algorithms to promote the posts of opinion leaders in various sectors (for example food, beauty and apparel, travel, and sports) to help them build and grow fan bases, instead of prioritizing the posts of celebrities and pop stars as it did in the past. To further energize the online marketing ecosystem, Weibo hosted a festival last summer to promote fan-based, internet celebrities. For key opinion leaders with smaller influence, it launched an open platform to help them connect with online vendors and service providers.

Extending its service to a new customer niche helped Weibo overcome growth stall and secure its current market success. Weibo is one of the major engines behind the fan economy in China. It is one of the best platforms for new startups to reach and grow a fan base. Two years ago, I witnessed the surging growth of a Weibo account targeted at a specific fan community. Its fan base grew from 200 followers—I was one of them—to a fan base of half a million within two months.

Weibo’s comeback shows the importance of growth development in China and elsewhere. In an age characterized by fast-paced design innovation and rapidly-changing technology trends, no company can afford to ignore user engagement.