Introduction

I first learned about user experience as a toddler teacher. My lesson planning included the most remarkable activities I could find, only to have all my little toddlers wander away in less than five minutes. This experience shifted my perception of what it means to be human-centered. As I learned to follow these little humans, observe, and get to know them, I realized I needed to focus on the entire human experience, not just the individuals.

Taking an Ecological Perspective

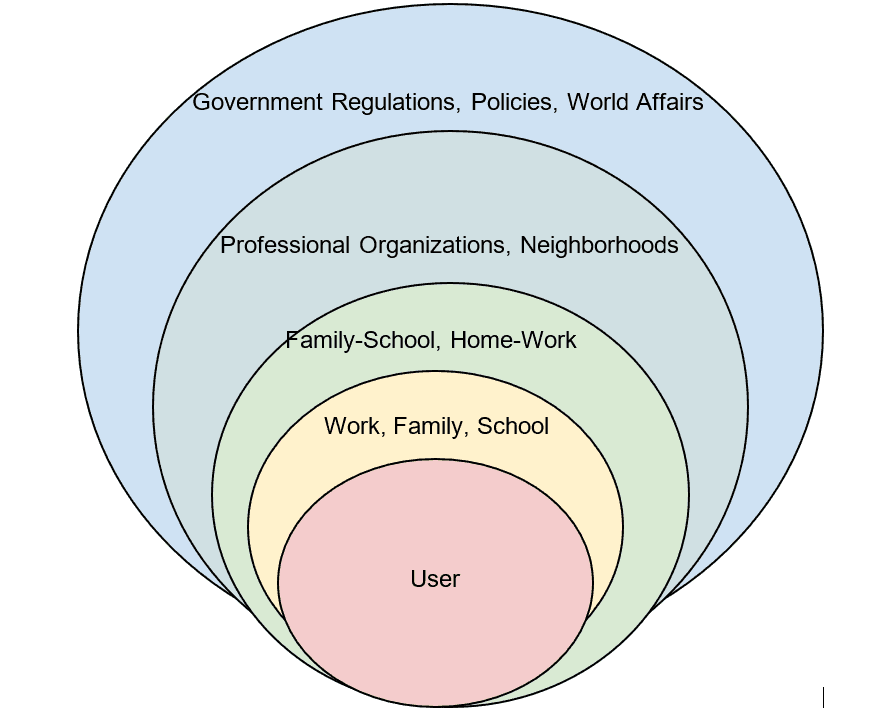

During my graduate studies, I moved into early childhood education and encountered a theorist, Urie Bronfenbrenner, who was also the thought leader for the low-income school readiness program I worked for. Bronfenbrenner’s philosophy examined the ecology of young children to support them adequately at every level. His ecological perspective included exploring direct influences such as families and schools and larger systems such as government policies.

Although I understood this philosophy as a teacher, it took a few years to fully embrace it as a researcher. UX research often focuses on those using a service or product, so that was my focus. I interviewed users, observed their work, and sent out numerous surveys. Every time I reviewed the results, I could not get rid of the feeling that something was missing. The data revealed how learning, company norms, and government policies changed adoption behavior. It was then that I fully understood that I was taking the user out of their context when I should have been studying the human experience, just as Bronfenbrenner had recommended.

Direct Systems

You may wonder what a user’s ecology looks like. Consider the things that influence our everyday behavior. The first level of the ecological system includes direct influences like school, home, and workplaces. For example, we may use specific software because that is what our school offers, or we may use an iPhone if our family also uses Apple products. These systems influence our thinking in ways we may not even realize because they feel like obvious choices.

The second level includes the relationship between two direct systems. Students are often influenced by family-school partnerships that create consistency in their learning. This shows up in other ways as well. Employees may use certain health programs at home because their workplace endorses or offers a discount for them. This changes how employees engage in a healthy lifestyle.

Indirect Systems

Indirect influences also play a role in how users experience the world. Indirect influences are things that have an impact on our world, but we may not notice them because they do not directly interact with us. One example is a neighborhood or a group that influences our direct systems, like a parent-teacher organization or a school board. We don’t interact with these entities daily, but these groups create policies and programs that influence the school culture and social norms. Examples of this could include a cultural festival organized by the parent-teacher organization or an anti-bullying policy passed by the school board to promote inclusion.

Another key example of an indirect system is government policies. Government bodies may pass laws, publish standards, and enforce regulations. How law shapes our cultures is not always noticeable. For example, if you are researching civil construction, policies around road construction, products the government chooses to use, or even security regulations can impact what officials decide to enforce. Further, in this age of technology and social media, there are global and media-driven factors to consider. World events and trends can cause a group or users to embrace one behavior or another.

Just as human experiences vary, each user’s context will have different systems that impact the human experience. The ecological map (Figure 1) is an example of the systems that directly or indirectly interact with a user. This context helps give a holistic view of their experience.

Figure 1: The user ecology map includes multiple levels of direct and indirect systems.

Using the Ecological Perspective to Design Change

The first time ecological perspective strikingly mattered was in my teaching career. I had a reserved little boy in my classroom. Jay was helpful, caring, and often kept to himself. He had not said a sound by the age of 2.5 years. Teachers pressured him to speak, but he would not say as much as a grunt. I spent days observing Jay’s behavior and body language. I started to feel that it was not that he could not speak but that he seemed to be choosing such a path. To test this hunch, I started noticing the rare situations in which he would make some sign or use body language to communicate. It became clear that he wanted to engage in the world but was unsure how to. After reviewing his file, talking to human services, doing a home visit, meeting with his mother, and talking to his siblings, it became clear that Jay felt unsafe speaking. Then I learned about Jay’s family’s struggle to separate from his abusive father, who went to jail for charges of murder. They escaped to a homeless shelter before securing a place in the transitional housing unit where the children attended the school readiness program.

The interventions we designed for Jay were failing because we had not taken the context of his situation into account. We encouraged him to speak when he needed us to make him feel safe. My co-teacher and I decided to focus on safety rather than encouraging him to speak. Before turning three years old, Jay started saying common words such as “milk.” Within three months, he was learning in the preschool room, and his teachers complained that he would not stop talking!

We are a sum of our experiences. Understanding the range of this experience can allow us to unveil a problem differently and design an experience that shifts behavior.

Many things are involved in building a human experience. By mapping out these ideas, you can apply this information in your next research project. For the sake of this article, I will demonstrate mapping with an example from education.

Exploring the Ecology

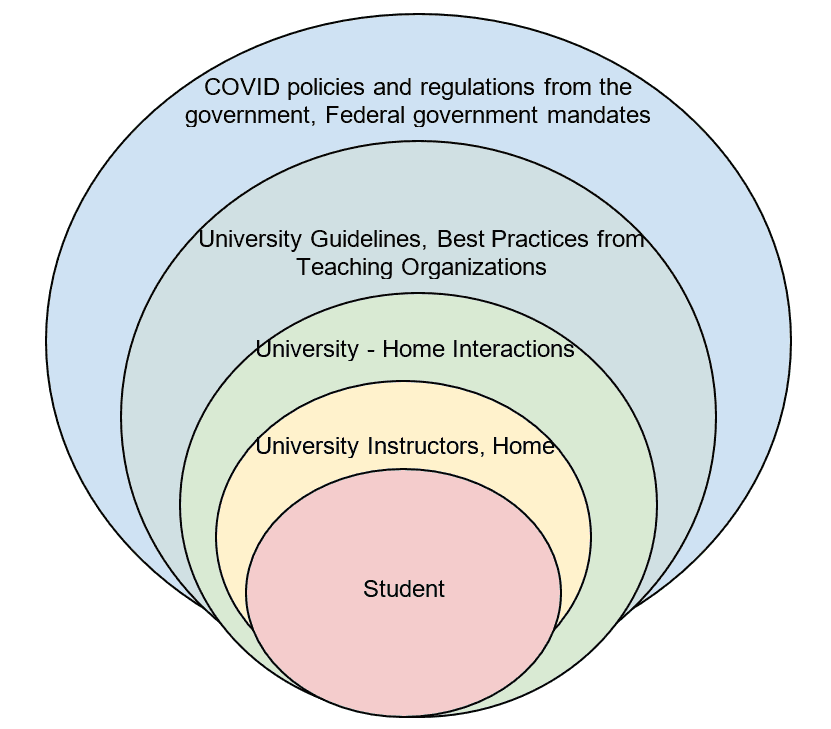

First, it’s helpful to map the systems that influence the user. This example is based on a learning design project I worked on with arts faculty at the university during the onset of the pandemic.

We aimed to design a human-centered learning experience for university students during the COVID pandemic, so we asked ourselves these questions to think through the direct and indirect influences:

- Where does the student go to school? Where do they spend their time?

- Where do they live?

- What neighborhood or region do they reside, work, and/or go to school in?

- What regulations are being enforced? What entities are enforcing them?

Figure 2: An ecology map explores student learning during the pandemic.

Mapping the Problem

In the example (Figure 2), university instructors had been informed of university mandates and best practices, so we interviewed instructors to understand their teaching goals better. Home life had a massive impact on learning during the pandemic as many students could no longer live on campus or were isolated to their residence halls. Investigating safe practices helped discover any opportunities or alternate learning environments that could be used.

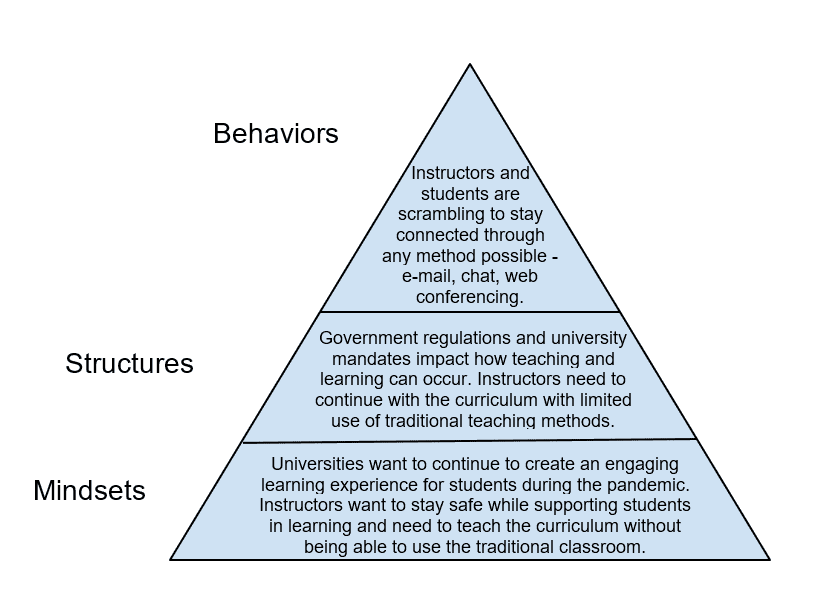

Figure 3: A problem map shows the mindsets, structures, and behaviors that emerged at the onset of the pandemic.

A human-centered strategy can include this format of problem mapping, but there are other ways to map a system, including process maps or even stakeholder maps to capture influences. The goal of mapping is to form a holistic picture to assess opportunities to create change.

Leverage Points

The behaviors in the problem map are where we want to see a shift. If we influence the mindsets, we may invest in culture change or professional development. The structures are areas where we can change the behavior directly. At the university, we conducted workshops to broaden the thinking around learning environments to learning spaces that included virtual space. In addition, we focused on the structures that we could influence. Although we had limited influence on the policies and regulations put forth by the university and government, we could assess the use of university spaces and technology to achieve the learning outcomes desired by instructors.

Donella Meadows, author of Thinking in Systems, describes leverage points as “places where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything.” Leverage points can be things that reinforce a behavior to entire paradigm shifts. The best place to examine leverage points is in the structures part of the problem map because structures influence behavior. In the example, it is clear that the government and university best practices and safety guidelines prevented traditional classroom spaces from working as a structure during COVID. Technology was used minimally prior to the pandemic.

Taking a design thinking approach, we aimed to discover, “How might we use university spaces and technology to create a more effective learning experience for visual and performing art students?” We were able to brainstorm ideas such as these:

- Using other university spaces: While traditional classroom spaces would not work for safety reasons, the university had an outdoor amphitheater and a lot of open space to hold performance courses.

- Utilizing different tools: Instructors were concerned about masks not allowing students and instructors to show facial expressions or project their voices for performances. Face shields and microphones were used as a safe way to achieve this.

- Expanding technology: Technology was minimally used at the onset of the pandemic. Digital storytelling through Zoom and recorded videos allowed instructors and students to collaborate safely. Learning management systems and chat helped build community.

These small shifts enormously impacted the student experience and allowed instructors to continue with their curriculum as desired and mandated by the university.

Honoring the Human Experience

Taking an ecological perspective allows us, as UX designers and researchers, to look beyond what we typically observe and notice the values and preferences of our users in the world they live and work in. Acknowledging their overall experience and mapping their experiences can be useful to discover unconventional ways of shifting behaviors. By taking an ecological perspective, it will be easier for you to evolve your work by exploring options that are not apparent. Honoring the entire human experience, instead of focusing on one piece of a person’s experience, allows the world to open up and yield some surprises.

Dr. Namita Mehta leads the Research Innovation Lab at Trimble. She has 20 years of experience conducting human-centered research, program evaluations, and organizational culture assessments. Namita has a strong commitment to equity and inclusion.