English was the first language used on the internet, making up approximately 80% of all internet content by the 1990s. However, as Holly Young explains in “The Digital Language Divide,” “English’s relative share of cyberspace has now shrunk to about 30%, while French, German, Spanish, and Chinese have all pushed into the top 10 languages [used] online.”

As people continue communicating online in hundreds of different languages, the technologies we use to translate information between languages have also continued to evolve. For example, Google’s Translator Toolkit and Skype’s multi-language translation script translate content into more than 130 languages. Cross-language Information Retrieval Software (CLIR) (for instance, Google searching) allows users to search for information in one language and get results in multiple languages at once. Social media platforms like Facebook provide instant translations of posts, so content once limited to a specific audience is now more widely accessible.

While these digital translation tools certainly provide more options and resources for people who want to interact across languages online, users can still encounter problems. Rather than being informed by user experience research, digital translation software is designed through machine algorithms that predominantly measure grammatical and lexical accuracy. Most current digital translation tools operate on a translation-as-replacement model. Users type in a word or phrase in one language, select the desired target language and click “Translate.” The equivalent word (or a selection of equivalent words) in the target language then appears on the screen.

While this type of substitution-based translation can help users understand some content, according to researcher Ahmed Abdel Azim ElShiekh, digital translation software still has an “inability to account for ambiguities” or complexities in languages other than English. The reliance on machine algorithms and the lack of user experience research completed on digital translation has left big gaps in the capabilities of this software. To improve digital translation tools, we must understand how users navigate across language online during everyday activities as they incorporate cultural knowledge and localized experiences in their translations.

Researching how people who speak multiple languages use digital translation tools can help designers and user experience researchers visualize how human beings transform information across languages, with the knowledge that these tools are just one piece of successful multilingual communication.

How Can We Understand Translation in Practice?

As a bilingual (Spanish/English) user experience researcher and teacher who also works as a translator for various organizations and projects, I’ve been tracing how multilingual communicators manipulate digital translation software to meet their translation needs in different communities.

Drawing on my research, I present three data narratives that illustrate how multilingual communicators use different digital translation tools to complete their work. Through these data narratives I argue that digital translation software can benefit from more user experience research conducted with (and by) multilingual communicators, and then make specific recommendations for how this UX research can be incorporated into the design of future translation technologies.

Data Narrative 1: Digital translation tools as sites for inspiration

During my research, I collaborated with bilingual (Spanish/English) news broadcasters who work at Knightly Latino News, a university campus news network that focuses on writing and translating news stories to meet the needs of the Latinx community in Florida. I worked closely with two student translators at this organization, recording their computer screens during translation projects and then holding post-translation interviews to better understand my participants’ translation practices. During these interviews, the translators and I would watch portions of their screen recordings together, and would then have a conversation about what was taking place during these recordings. I asked translators questions like, “Why did you decide to use this particular definition or digital translation tool? Why did you go to that specific website while you translated?” In this way, the post-translation interviews helped me further understand how participants made decisions and coordinated resources as they translated information.

During one of her translation recordings, one of my participants, Natalie, was translating a news story originally published in English. The story described a new housing development set to be built on the grounds of a popular park in Orlando, Florida.

As she translated this story during a 30-minute writing session, Natalie used Google Translate 32 times to find possible translation options or to double-check the translations she came up with on her own. Although Natalie accessed Google Translate 32 times, she only used 14 of the Spanish words suggested by Google Translate in her final article. The rest of the time, according to Natalie, the Google Translate suggestions served as “inspiration” for her translation process.

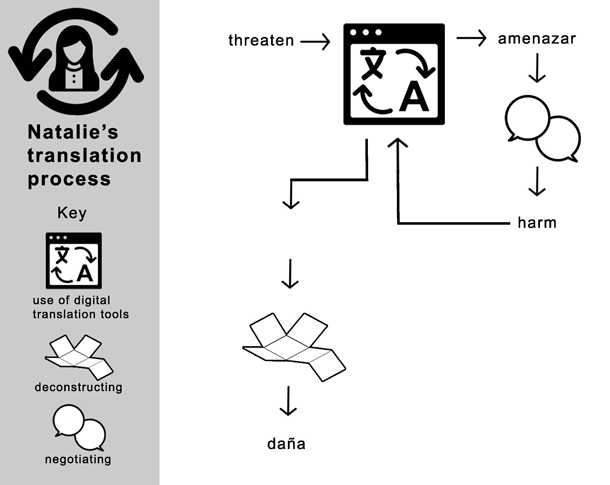

For example, Natalie began translating her new story from English to Spanish by looking up the word “threaten” using Google Translate. She wanted to translate this word because it was used in the article’s title, “Development Plans Threaten Orlando Park.” When she searched for Spanish translations of the word “threaten” using Google Translate, Natalie received four options: amenazar, proferir amenazas contra, acechar, and amagar. All of these words and phrases were identified by Google Translate as synonymous to the English word “threaten.”

Rather than using any of the initial options provided by Google Translate, Natalie searched for Spanish translations of the word “harm.” Google Translate provided nine options for this translation, and Natalie decided to use the first option, the word daño, in her final article. Figure 1 illustrates Natalie’s translation process.

During her post-translation interview, Natalie explained that she didn’t use any of the initial suggestions provided by Google Translate because “the word threaten seemed to be translated into something more related to physical harm.” Natalie continued, “If I amenazar someone, for example, I’m threatening them physically. Threatening a park is completely different, so I decided to look up options for the word harm because I thought that might give me results that are more like harming a physical object instead of a person.”

In this example, Natalie knew the intended audience would understand the suggested translation amenazar as referencing physical harm rather than harm to an object or landmark, such as a park. To get a more accurate translation of the word “threaten” in Spanish, Natalie used her own comprehension of the English language and looked up the synonym “harm,” using those results instead. As Natalie explained, the translations provided by Google Translate “are just inspiration sometimes.” She continued, “I wouldn’t have thought of the word dañar on my own necessarily, but seeing that amenazar was an option helped me think of similar words to look up in Spanish and English. The Google translations gave me options.” For Natalie, Google Translate served as a tool to help or “inspire” her own abilities to move between languages, rather than as a tool to find specific translation “answers.”

Data Narrative 2: Accuracy vs. cultural knowledge in digital translation

I collaborated with HQ Grand Rapids, a nonprofit drop-in center for youth experiencing unsafe and unstable housing situations in Grand Rapids, Michigan. To support runaway and homeless youth, HQ hosts several presentations and events, for which they produce promotional materials (for example, fliers, invitations, Facebook events).

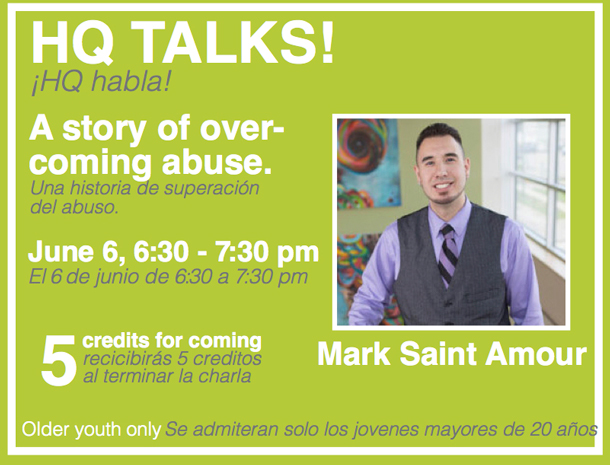

During this collaboration, I was asked to proofread an event flier translation that was shared with Spanish-speaking youth in the Grand Rapids area. The flier (depicted in Figure 2) described the presentation event title as “HQ Talks!,” which was originally translated as “HQ Habla!”

Rather than relying strictly on my own expertise to proofread the flier, I held a focus group with Spanish speaking youth at HQ, where participants shared their ideas for translation based on their own linguistic and cultural knowledge and their past experience with “HQ Talks!” events.

During this focus group, participants and I used an online translation dictionary, Linguee.com, to come up with initial translation for “HQ Talks!” Focus-group participants were less concerned with having grammatically “accurate” translations of information provided by Linguee than they were with seeing Spanish words that resonate with their own perceptions and feelings toward HQ. For example, when I asked focus group participant Ana if she thought the translation “HQ Habla!” was an accurate representation of “HQ Talks!,” she explained, “Yeah, it’s a grammatically accurate translation, but for me, when I attend ‘HQ Talks!’ events they are more of people telling their own stories of survival. I know that with other events like this one, the stories will change, but they are less of a talk and more of a story.”

When I asked Ana what term or phrase she might use to describe “HQ Talks!” events in Spanish, she mentioned “Cuentos en HQ,” because the word “cuentos” signals a storytelling event that is taking place at HQ. Even though “cuentos” is literally translated to “stories” and is not a translation option for the word “talk,” it was the word Ana deemed most representative of the experience she felt at the “HQ Talks!” events.

Ashley, another focus group participant, had a similar reaction to the phrase “HQ Habla!” Ashley explained that any event at HQ is “more of a get-together than a talk.” For this reason, Ashley suggested the phrase “Junta de HQ” as a potential name for this event series, explaining that the word “junta” (literally meaning “get-together” or “together”) better represents the gathering and general closeness that members feel at these events.

Like the translators at Knightly Latino News, bilingual focus group participants at HQ used digital translation tools (for example, Linguee and Google Translate) to come up with some options or ideas for their translations. However, participants in both groups then expanded on the options presented by machine translation by thinking closely about their own knowledge of the specific communities that use the information, and thus came up with options that were both accurate and culturally appropriate.

Data Narrative 3: Translating with the body

While studying translators’ engagement with digital translation software, I collaborated with the Language Services Department at the Hispanic Center of Western Michigan, a small business located within a bigger nonprofit organization aiming to support the Latinx community in and beyond the state of Michigan. The Language Services department employs more than 30 translators and language interpreters who provide language accessibility for their community by translating fliers, websites, and legal documents, as well as other resources for various government, medical, and community organizations.

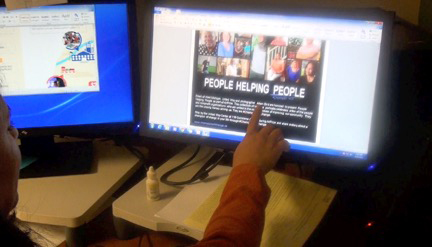

I observed the Director of the Language Services department, Sara, as she translated a flier for an upcoming community event titled “People Helping People.”

As depicted in Figure 3, while Sara completed her flier translation, she had two computer screens with several screens open. Sara consulted several digital tools to complete this translation, including visiting Word Reference, a digital translation tool, to find translation options for several words. In addition to these digital resources, Figure 3 shows Sara pointing her finger at the screen, moving her fingers back and forth while translating. As Sara moved her fingers back and forth on the screen, she visualized how the various grammatical structures could be presented in both Spanish and English, deciding how she could structure her translation in a way that would be appealing and useful to Spanish-speakers. Although she could see different translation options on the screen, Sara pointed at different words and used her fingers to cover and combine phrases as she translated the flier.

In holding further conversations about translation events with Sara and other employees, I learned that sometimes translators have to “feel translations” as much as they compose them. “Feeling translations” means not only seeing words digitally on a screen, but also testing out how users will engage with information in their material contexts, with a printed flier, a multi-layered website, or other materials that extend outside of digital spaces.

To “feel translations,” translators may engage in conversations while standing and gesturing, sit in various rooms with different types of lighting to look at a document, and/or print digital materials in large font to see how words fit on a printed page. Reaching accuracy in language transformation encompasses the combination of several resources, including digital interfaces, printed material, and human connections.

Conclusion: Translation Between Digital and Material Worlds

The brief (and admittedly limited) translation events presented in this article provide just a few examples of the many activities multilingual communicators engage in as they transform information across languages. As my data narratives demonstrate, translators cross boundaries between spaces, languages, and cultures to complete their work. Using these data narratives to think about the connections between virtual and real worlds for this issue of UXPA, I make the following recommendations for user experience researchers interested in studying and designing virtual and material interfaces to improve future translation technologies:

Recommendation 1: Recognize translation as a cyclical process

Many current digital translation tools position translation as a linear process. After you input content and hit “translate,” digital translation tools provide various translation options, much like a thesaurus may yield several different synonyms for any word.

As Natalie demonstrates in her translation of the word “threaten” in Data Narrative 1, the translation options presented by digital translation software are not all created equal, and choosing the correct translation may require several rounds of revision. Thus, as user experience researchers continue studying the use of digital translation software, it might be important to recognize and trace how translation can be treated as a cyclical event with ideas moving from the original language to the target language and back again.

User experience researchers can further consider how users’ experiences with language in the real world may affect their own perceptions of the options presented by digital translation technologies. Creating a space for cyclical translation work in digital spaces should be a priority in the next design phase of translation tools.

Recommendation 2: Approach translation research and practice as creative, rhetorical acts

My analysis of translation in practice demonstrates the highly creative work that multilinguals put into translation. There is often not a simple one-to-one replacement for a translated word. The best choice is determined by a number of competing and complex factors such as context, culture, and connotation—factors that are not always recognized in the design of current digital translation tools. Transitioning to a creative perspective on translation has implications not only for translation tool design but also for the role we assign translators in the design process. Viewing translation as a creative act demands that we place greater value and recognition on the services translators provide. Further, understanding the creative and rhetorical potential of digital translation requires that we design digital translation software that incorporates nuances and intricacies in multiple languages.

Currently, as researchers Jiangping Chen and Yu Bao demonstrate in “Cross-language Search: The Case of Google Language Tools,” digital translation algorithms are designed with English as a central component. This means, for example, that if translators want to translate content from French to German (or between two languages other than English), digital translation tools will present more accurate options if users first translate their content from an initial language (for instance, French) to English, and then translate this English content into their target language (for instance, German). This algorithmic limitation does not allow for much flexibility and representation in languages other than English, blocking the potential for more creativity and flexibility in translation processes.

Future iterations of digital translation technologies could implement user interfaces that situate word and phrase options in various rhetorical and linguistic contexts, allowing users to input and receive translation options in a wider range of languages.

Recommendation 3: Develop translation algorithms from research on human behavior

The data narratives presented in this article introduce the varied ways that translators combine their use of digital translation software with other activities, including gesturing, storytelling, and recalling memories, as well as collaborating with other bi- or multilingual communicators. While lexical and grammatical conventions played a role in translators’ work, these conventions were often adapted and repurposed.

For example, the event names at HQ in Data Narrative 2 may be perceived as grammatically incorrect (containing incomplete sentences and colloquialisms), yet these translations were frequently deemed more appropriate for the HQ community than the technically correct options provided by digital translation software. In Data Narrative 3, when Sara was presented with grammatically correct options for her translations using Word Reference, she moved her fingers on the screen to visualize other potential sentence structures.

As these brief examples demonstrate, user experience research on translation can further benefit from developing protocols that account for human activity as it takes place both on- and off-screen during translation processes. In thinking about the design of future translation technologies, user experience researchers can use these frameworks to help build translation interfaces that present translation options in more than just written form, allowing users of this software to see how translations may be verbalized and paired with embodied gestures. By building translation technologies that account for written linguistic conventions in conjunction with more contextualized uses of language, we can acknowledge the multiplicity of ways through which language is used and constantly adapted. There may never be a way for digital translation tools to fully or sufficiently account for the ambiguities of language and the complexities of human behavior. In a sense, the examples presented here are a broader argument for the role and value of human translators in successful language adaptation. At the same time, however, considering the activities of human translators and their engagement with current digital translation technologies can provide useful avenues for conceptualizing the possibilities for dynamic, culturally situated translation tools and their influence on linguistic diversity on the internet.

As the capabilities of digital translation software grows, user experience researchers can consider how different types of usability tests and collaboration with multilingual communicators may increase the extent to which people can share ideas and engage in conversation beyond the boundaries of any single language.

[greybox]Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Knightly Latino News at the University of Central Florida, the Language Services Department at the Hispanic Center of Western Michigan, and HQ Grand Rapids for their collaboration on this project and for their continued commitment to providing language accessibility in their communities. In addition, I’d like to thank the UXPA editors for their support, and Jennifer Sano-Franchini for providing feedback on an earlier version of this article through our work with the Smitherman/Villanueva Writing Group sponsored by Adam Banks and the Writing and Rhetoric Program at Stanford University. Additional thanks to Heather Noel Turner for creating the illustrations in this article for my forthcoming monograph to be published in the Sweetland Digital Rhetoric Collaborative Book Series by the University of Michigan Press.[/greybox]