It’s New Year’s Eve and friends are at my apartment celebrating the ball drop on television. Streamers are flying, and people are getting ready to clink champagne glasses. Suddenly, all the lights dim, leaving the apartment 50% darker than it was before, and everybody gasps. “Sorry,” I explain. “They’re smart lights that dim at midnight.” I quickly wrestle with various menus on my phone to turn off the automated schedules. These lights have worked wonders for improving my sleep by gently reminding me to go to bed at night. Still, they weren’t aware I’d have my friends over on a special night when I’d be up later than usual. With smart lights come new problems.

With New Capabilities Comes New Complexity

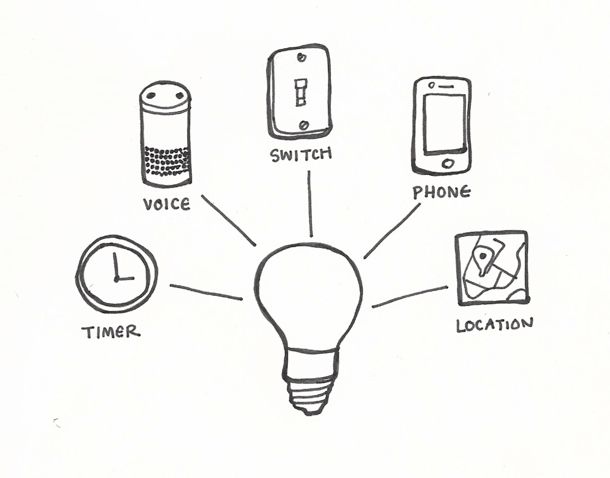

In the world of Internet of Things (IoT), a light can be turned on not just from a switch, but also by asking Alexa, tapping a button on your smartphone, through an invisible schedule, or by an automation that’s triggered when you walk in the door. Lights which were—for about a century—operated by a simple on-off fixture, are more capable and complex than ever. These interactions not only affect the experience for primary users, but for their families, roommates, and guests. These are new variables that designers of IoT products need to consider. With the advent of this new technology, we need to adapt the way we design and make sure that we solve problems in ways that are inclusive of everybody in the household.

When I first started as a designer at an IoT company, we created experiences that were suited for us. The employees were mostly single, living in urban apartments, and working long startup hours at a dusty garage in New York City. Flexible whiteboards that reached from floor to ceiling were lined with big, markered sketches of mobile screens. These were the blueprints for our vision of the smart home: a system that would enable a single tech-savvy user to take anything from a light, garage door opener, lock, or thermostat and program it to do whatever they wanted in the home.

Designing for Tech Savvy, Early Adopters

We attracted a vocal group of early tech-savvy adopters who reflected the creative spirit of our employee base. They loved the features we built that focused on configuration and customization of smart home capabilities. Our core interaction paradigm was based on the engineering logic of “if-then” statements, and was intuitive for technical-minded users to grasp. It was all editable by a single smart device. We iterated a lot based on the feedback of this early group, and built even more customization features. The platform was becoming more powerful than ever, but the adoption and engagement numbers weren’t looking as good as we had hoped. We would spend months building advanced features, but not see any improvements on the goals we were trying to hit.

When it became clear that our current feedback and iteration loop wasn’t working, I decided to venture out and visit the homes of our users to find out what was going on. Why were they no longer engaged with the platform?

Conducting Immersive Research to Understand IoT Experiences

Over the following months, we met with dozens of users in their homes. We met a young professional who purchased his first small home on Long Island and had to forcibly download our app onto his parents’ phones so they could unlock the door to his house. A fashionable couple who ran their own creative agency out of a high-ceilinged loft disabled their automations during client meetings to prevent accidentally plunging them into darkness. We met a mother of three in the suburbs whose spouse set up an automatic light to turn on when she came home so that she wouldn’t have to fumble with the switch.

A major theme in these studies was that interactions on our platform were affecting family members and guests in ways that we weren’t aware of or measuring. These were factors that our adoption and engagement numbers alone couldn’t tell us. Conducting immersive research studies in users’ homes became the core way for us to fill in the gaps of what was happening on our IoT platform. In fact, they added the “why” behind the confusing adoption and engagement numbers.

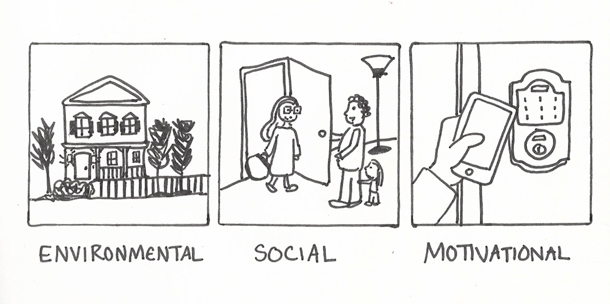

Our analysis of users’ surroundings also enabled us to observe the environmental, social, and motivational context behind how households were experiencing our service.

- Environmental context. Where are the IoT products placed and what are they surrounded by? A device that is placed in the front and center of a household will have a better chance at communicating to users with visual cues than one that is hidden from view in a closet.

- Social context. Who else lives in the household? A family of five where only one person has the controls for the lights on their phone will need an alternate way for other family members to interact with the lights.

- Motivational context. What was the reason for having the IoT products put in place? Products that were bought to participate in a holiday light show would only be used seasonally, compared with products that were bought for everyday utility.

Shifting the Roadmap to Design for the Household

Gaining this additional perspective from in-home studies fundamentally shifted our internal culture and how we thought about our roadmap. Previously, our features centered on solving our own problems and those of tech-savvy adopters in a way that was suited for the individual user. Our studies, which revealed many unsuspected complexities, enabled us to shift our focus to the entire household. This, in turn, helped us in designing a platform that worked for everybody whose lives were affected by our decisions.

Using Storyboards to Communicate Context

With these new insights and newly found context, we shifted the way we communicate our designs and experience. Previously, we presented designs by sharing mockups or isolated prototypes of the mobile screen. A typical design review may have been, for instance, a demonstration of variations of “on-off” toggles for a light’s UI. Still, armed with new insights from in-home research, we began to depict our experiences using detailed storyboards showing the environmental, social, and motivational context.

In design reviews we would share a storyboard of someone rushing home to a dark porch—grocery bags in one arm, child in the other—unable to reach for their phone, let alone open an app and toggle a switch. Such a storyboard enables the team to focus on what the user is trying to do in that moment and build a way to solve their problem. In effect, it takes the team out of an isolated mindset of designing for one person and thinking of the in-app experience only. This captures the holistic experience—within the app and outside of it—with an understanding of the user’s motivation, where they are, and who else is around.

As technology becomes more ubiquitous, the challenges of designing for IoT and multi- device experiences will only continue to grow. It is increasingly important that we look beyond the quantitative metrics and our own assumptions and fill in our understanding by observing real users in their actual environments. A more complete understanding of context will enable the IoT experiences we design to solve real problems, be adaptable, and make sense of everything around. Perhaps, at a future New Year’s party, my lights will know not to plunge my guests into darkness as the clock strikes midnight because the people who built it truly anticipated my needs.