The US Federal Government creates and supports a vast number of websites, electronic systems, and other types of products. Many of these are complex and often serve a wide variety of uses and users. All this development provides a lot of opportunity for user experience work (Figure 1).

Fortunately, there are many people working hard to improve the users’ experience with these systems. The UX professionals working in government agencies face a number of obstacles and challenges, but there has also been some significant progress as well. In this article, I will share some challenges that are unique to UX work in federal agencies and some that may also exist in other types of organizations. I will also share some lessons learned and good news about UX in the US government.

Government UX Challenges

Everyone doing UX work faces challenges of one sort or another. Professionals working in government agencies face these general challenges as well, but some are unique to the US Federal Government.

Paperwork Reduction Act

One of the biggest challenges in government UX work is the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) of 1980, amended in 1995. This law requires federal agencies to submit proposals for studies involving more than nine participants to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review and approval. This law applies to all UX methods involving participants, including usability testing, focus groups, card sorting, and surveys. The purpose of this approval process is to ensure that government research is sound and appropriate and to protect the public from unnecessary burden.

There are certainly benefits to having a third party review research plans, as Institutional Review Boards do at universities. However, the PRA process is complicated and lengthy, possibly taking six months or more to complete, making it difficult or impossible to conduct meaningful user research.

OMB offers a “generic” clearance, where an agency submits an application to use general UX methods. Once OMB approves the general methods, the agency then submits short proposals for each study, which OMB may approve in as little as five days. This is much better, but the process for preparing the generic clearance application can be difficult, time-consuming, and complicated, especially for agencies with less experience with this process.

Luckily, there are resources to help with PRA clearance. DigitalGov and usability.gov both have information on the topic. Recently, I gave a webinar on the options available for OMB clearance. Anyone looking for more information should also check with their agency’s clearance officer, who is most likely in the Office of the Chief Information Officer (CIO), as internal processes differ across agencies.

Restrictions on Incentives

As OMB has some control over how agencies conduct research with participants, they can also regulate incentives. Some agencies are limited to incentives of $40 for a one-hour session, which is low compared to private industry. This can lead to problems with recruiting and no-shows.

One approach to address this problem is to spend more time recruiting participants. It is helpful to develop a rapport with them; contacting them the day before a test session can help reduce no-shows.

In addition to the dollar amount, agencies may be limited in the types of incentives they can offer. For example, at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), we can only pay participants by check and we need a signed, original receipt. This works well for in-person sessions (as long as the participant has a way to cash the check), but requires alternative solutions for remote sessions, such as hiring recruiters or paying through online testing services. Other agencies have different accounting requirements and can provide different forms of incentives. Some agencies have also done testing without paying participants at all.

Little or No Competition

Most US government agencies provide services that no other organization can provide. For example, some agencies provide benefits like retirement or disability. Others help protect the public by providing services such as emergency response, oversight of private and nonprofit organizations, or regulations for safe work environments. Still others, like BLS, provide objective information about the economy. This lack of competition can reduce the incentive to ensure that products and services are as efficient and effective as possible.

There is no “solution” to this challenge, but even without competition, it has been my experience that agencies really do strive to provide good products and services for the public. Additionally, many agencies are held accountable for the quality of their services by other government agencies or the general public. For example, the government IT dashboard shows the progress of government information technology (IT) programs at every agency.

User Populations of “Everyone”

There is a strong desire to make sure that everyone can use government products because government work is funded primarily through taxes. One result is that development teams may take the strategy of designing for an average user or a user with minimal abilities. Unfortunately, this strategy results in designs that do not meet the needs of numerous user groups.

In these situations, personas are a good way to encourage teams to think about all the user groups. Teams may have to prioritize design decisions for certain user groups, but at least they will be aware of the characteristics and needs of everyone using their system.

Common UX Challenges

In addition to the unique government challenges, there are also some challenges that others may face as well, especially at large, well-established organizations. These challenges are not insurmountable, but they can make it difficult to get UX incorporated into the development process.

Resistance to Change

Government agencies often resist change. Many agencies are large and risk-averse, making it difficult to overcome inertia and change long-standing cultures.

In some cases, however, there are valid reasons for resisting change. For example, when statistical agencies publish statistics regularly, they need to use the same procedures every time so users can easily make comparisons with previously published values. These comparisons are critical to an accurate understanding of the state of the economy. Changing the process could impact the ability to compare changes over time.

In other cases, systems are so complex that even small changes have large ripple effects on other components or systems. It is expensive and risky to make any changes, including UX improvements. This is just the nature of large systems.

Of course, there are also cases where there is just a reluctance to try new methods. In these cases UX professionals can use common practices to help support UX, such as starting small, fitting work into the existing development schedule, educating leaders, and finding a champion.

Lack of Support for UX

Another common challenge is a lack of management support for UX. Even though much of the early work in human factors that led to today’s field of UX was government work (starting in World War II with the development of complicated military systems), that focus has not extended to all government agencies.

One reason for the lack of support for UX is the challenge of proving its value. There is not much quantitative proof that UX provides a return on investment and the evidence that exists is often ignored. Management may deem research in other domains irrelevant to government projects. Further, federal UX professionals often make recommendations from tests with fewer than ten participants (to avoid triggering PRA requirements). This does not provide powerful evidence in organizational cultures that are largely quantitative in nature.

To address these challenges, some of the approaches for dealing with resistance to change can help as well, such as starting small and finding a champion.

Lack of Awareness about UX

Many agencies are just not aware of UX. They are knowledgeable about their domain, but UX has never been a part of their work. This challenge is related to the resistance to change, in that agencies may not actively seek new ways of working.

There are a number of approaches to help promote UX, including:

- Taking all opportunities to discuss the importance and benefits of UX whether in meetings or informal discussions

- Giving presentations on UX for agency staff

- Conducting marketing activities, such as holding open houses in a usability lab or displaying marketing materials in public places

- Conducting hallway testing, which can help make UX work more visible

Limited Resources

Many agencies could use more resources for UX work. Lack of awareness and appreciation of UX, as well as long-term budget limitations, contribute to the lack of resources. This is a difficult challenge to overcome, but people are trying to do more with less.

For example, it may be possible to do some UX work with just a little training. Following Steve Krug’s “Rocket Surgery Made Easy” model of usability testing, the Government Services Administration (GSA) ran a program called “First Fridays” conducting usability testing on government websites on the first Friday of every month. The tests were short (just three participants) and focused on identifying five problems that the agency could realistically fix. Over time, First Fridays evolved into a training program for staff at GSA and other agencies.

This approach doesn’t replace experienced UX professionals on complicated and critical government systems, but it can be useful for many government websites. Although this program is no longer active, it did provide some good UX work and training for government employees and has served as a good model for other agencies.

Another approach is to train staff members to conduct some UX research. For example, the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) wanted to get feedback about their surveys from respondents by interviewing them in person. However, the respondents were farmers who lived in rural parts of the country far from the Washington, DC office of the research staff. The researchers decided to train some of their regional staff to conduct the interviews. With this program, they drastically reduced their travel expenses and were able to work with more respondents. They found that although not everyone is suited to this work, some people were and they could conduct more interviews for most studies without the expense of travel.

Good News

Despite the challenges of conducting UX work for the US Federal Government, there is also some good news: there are a lot of people doing a lot of good work to try to improve government products. There are several laws requiring government agencies to make government systems and communication simple and usable. There are also several resources that can help those doing government UX work (and those outside the government as well).

Official Directives

There have been several recent directives from the White House that are related to UX. In 2011, President Obama issued Executive Order 13571, “Streamlining Service Delivery and Improving Customer Service,” which requires agencies to provide more services over the Internet to better meet users’ needs. The executive order requires agencies to “improve the experience of its customers.” Although this Executive Order does not specifically call out UX methods, it clearly shows that the President is demanding agencies pay more attention to their users.

In 2012, the Federal CIO published “Digital Government: Building a 21st Century Platform to Better Serve the American People,” a Digital Government Strategy for agencies to meet the goals established in Executive Order 13571. The document was a collaboration involving many people across government agencies, ensuring it provided a thorough and realistic framework.

One of the four principles of the strategy is for agencies to take a “customer-centric approach” as they transform their digital services. Included in this principle are three milestones:

- Deliver better digital services using modern tools and technologies

- Improve customer-facing services for mobile use

- Measure performance and customer satisfaction to improve service delivery

Again, this directive did not mention specific UX methods, but the strategy clearly places an emphasis on the importance of creating usable products.

In 2014 the administration released the Digital Services Playbook, a checklist of best practices for building quality digital services. These best practices reflect the importance of UX work with the top 4 of the 13 “plays” relating to UX:

- Understand what people need

- Address the whole experience, from start to finish

- Make it simple and intuitive

- Build the service using agile and iterative practices

Most recently, on September 15, 2015, President Obama issued another Executive Order titled “Using Behavioral Science Insights to Better Serve the American People.” In this Executive Order, President Obama notes that “the Federal Government should design its policies and programs to reflect our best understanding of how people engage with, participate in, use, and respond to those policies and programs.” The Executive Order calls for agencies to find better ways to use behavioral science data to support the design of government policies and programs. Again, the Executive Order does not call for UX methods specifically, but it does provide additional support for UX work.

So over the last five years, there has been a lot of support from the executive branch to better incorporate UX into the development of government products.

Section 508

Of the US laws on UX-related issues, “Section 508” is probably the most well known. This actually refers to “Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended in 1998,” and addresses requirements to make systems accessible. This law authorized the US Access Board (an independent US federal agency) to publish the Section 508 accessibility standards, which have been in effect since 2001. The law requires government agencies to follow the Section 508 accessibility standards for all software and websites, as well as other electronic equipment.

The Access Board is currently updating (what they call “refreshing”) the standards. The proposed changes would bring the Section 508 standards in harmony with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0, the latest accessibility guidelines published by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the main international standards organization for the Internet.

Although compliance with Section 508 meets the letter of the law, it is really just a good first step. Compliance does not guarantee that a system is accessible to all users, just as ensuring that all features on a product work does not guarantee that it is usable. As with usability, it is important to consider accessibility throughout development, and to conduct testing with actual users.

The Plain Writing Act of 2010

The Plain Writing Act of 2010 requires agencies to develop “clear government communication that the public can understand and use.” The act calls for executive branch agencies to:

- Use plain language in all communications

- Train staff to write using plain language

- Develop a process for monitoring compliance with the Act

A good source of information about Plain Language in government efforts is Plainlanguage.gov. This is a site run by the Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN), an inter-agency group dedicated to plain language. Their website has great resources for information about the law itself, as well as training materials and good “before and after” examples.

Government Resources

To help government agencies better incorporate UX into their development process, several agencies have produced training and informational resources, many of which are available to the general public as well.

DigitalGov

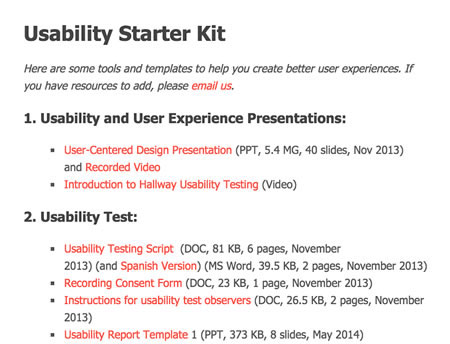

GSA runs DigitalGov, which provides resources for agencies producing digital services, including information about UX (see Figure 4). GSA sponsors training opportunities, both in-person and online, and they have a blog covering a number of topics, including UX. Although attendance at their training is limited to government employees, many of the webinars on UX topics are available to view online. They have a “Usability Starter Kit” which includes some basic information about UX as well as templates for documentation and information about government contracts and procurement. They also have a page on case studies showing how UX methods have improved government websites.

Usability.gov

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sponsors the website Usability.gov, which provides overviews of various UX-related disciplines, the user-centered design process, and information on methodology and tools for making digital content more usable and useful. The site also includes templates for UX-related documents such as consent forms, test plans, and test reports. Some of the information on the site is specifically government-related, but most topics are useful for anyone in the field. The site also hosts the well-known Research-Based Web Design Guidelines, a great resource for anyone looking for a rationale for design decisions.

The User Experience Community of Practice

One last resource for US government UX work is the User Experience Community of Practice, an online community to support UX work at all levels of the US government (federal, state, local, and tribal). Because this group is supported by government funds, it is open only to government workers and contractors with government email addresses. As of this writing, there are over 780 members of this group. This is a great sign that there are a lot of people in government agencies trying to improve the UX of their products.

Optimistic About Improved UX

With the complexity of the government’s structure, the sheer number of government systems, and the limited UX and related resources available, federal UX professionals face a number of challenges in getting their work accepted. On the positive side there has been much progress, with several laws and directives requiring that agencies attend to users’ needs. They have certainly helped motivate agencies to improve the UX of their products. There are also many talented people who are working hard to make great government products. I am optimistic that this will lead to better and better products from the US government in the future.

Thanks to Jon Rubin, Katie Messner, Kathy Ott, and Alycia Piazza for their help with this article.