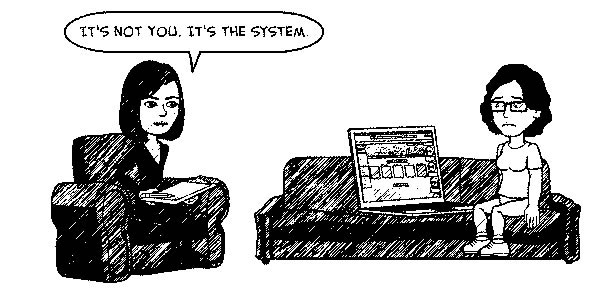

You are the therapist. The website/application/product is your client. Your job is to accurately identify and diagnose user experience (UX) issues prior to developing an effective treatment plan. Let’s look at how you might go about doing this.

First, my background: I am a psychotherapist turned user researcher, intent on bringing everything I learned as a therapist to UX research. Similarities between the fields are striking. Some people think that being a UX researcher is similar to being a therapist because you work with people—whether that skill is used in interviews, field observations, usability studies, or some other human-centered research. However, in the case of UX, we are not diagnosing and treating people. We are “diagnosing” and “treating”—in other words, improving—products to better serve people.

When writing user research findings, we do not frame an issue as a therapist might: “Participant 1 is unaware of the left-hand navigation and will require additional guidance to increase awareness. Treatment plan: weekly sessions of left-hand navigation awareness training.” Instead, we may write: “Left-hand navigation not discoverable. Recommendation: improve visibility by increasing font size, adding color or other design elements, and reducing clutter on the page.”

The diagnosis and treatment plan centers around the website, not the users. I’m sure we’ve all heard users blamed for UX issues in the past, with some saying that the users are the ones who need more training, information, better web skills, etc. However, since, in most cases, we are not planning to implement a training program to educate and train all users of a website/application/product, the onus is on us as professionals to improve our UX and to stop blaming the user. It benefits everyone if we apply a therapeutic strategy to UX in an effort to make sure that we properly diagnose and treat issues.

Constructing Evidence-Based Treatment Plans with SOAP Notes

When I was in training to become a therapist, I learned how to write SOAP (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan) notes after every session with a client. The purpose was to capture the core components of a session without getting too bogged down in the details. SOAP notes also helped to directly tie the client’s treatment plan back to a diagnosis made based on evidence.

How to Write SOAP Notes

SOAP notes are captured using the following process, and Table 1 illustrates how they can be applied to research reports:

Subjective (users’ point of view) – Capture the subjective feedback from users. What are users saying about their experiences? For example, this could include interviews, quotes, System Usability Scale (SUS), and any other measures where users are providing their perceptions and feedback about their experience.

Objective (your point of view) – Write down anything you observe about users’ behavior. For example, this could include their mood, eye movements, mouse clicks, how they hold a mobile phone, success in completing a website task, time on task, and errors.

Assessment – Look back at your subjective and objective notes to make a diagnosis of an issue. Taking into consideration everything you heard and saw, what’s the problem? Give it a rating. How severe is the issue? What category does it fall under (for example: navigation, design, layout, content)?

Plan – What is your plan to address the issue? This could include follow-up research activities that you would recommend for further diagnosis, or it could be design or technical recommendations to solve the issue. Your plan could also be a mix of next steps and recommendations.

Table 1. An example SOAP note

| SOAP Note Categories | Sample Data |

| Subjective | Participant 1: “I can’t find anything on this homepage. It’s too cluttered.”

Participant 2: “I don’t like the site. It looks too busy and it’s overwhelming.” Post-study survey: Design and layout score 1.5 out of 5 |

| Objective | 2 out of 5 participants sighed the first time they saw the homepage and leaned in to get closer to the screen. 2 participants put on their glasses when they saw the homepage.

5 out of 5 participants navigated to deeper pages to find an article that was located in the center of the homepage. Only one participant later found the article in the center of the homepage. 3 out of 5 participants did not scroll down on the homepage at all. |

| Assessment | Homepage is cluttered. Content and navigation need to be streamlined. |

| Plan | Review website analytics to further explore usage behavior.

Conduct a card sort study to learn how users would group different website content. Learn about the etiology of the cluttered homepage by conducting interviews with the website publishing team. |

When using the SOAP note method, you should strive to write one SOAP note for each major UX issue. The subjective and objective notes are the pieces of evidence you collected that lead to an assessment or diagnosis of the issue. The plan is the method you will use to treat your usability diagnosis.

Why SOAP Notes?

I’m sure for many of you, this is nothing new. You know that it is important to show evidence for a user issue (diagnosis/assessment) and come up with a plan for how to treat it. SOAP notes allow you to tie issues into a complete package and create templates over time for how you might treat common issues. By saving your SOAP notes from different user research projects, you can organize them into categories based on the assessment/diagnosis. This will allow you to refer back to your previous treatment plans for common diagnoses and you can see which treatment approaches were effective, improving and streamlining your recommendation process, similar to a seasoned therapist.

SOAP notes also help you tie multiple data points under a single issue with a diagnosis and treatment plan, making your recommendations solution-focused rather than just producing a log of bugs that focus more on addressing symptoms than treating the overall diagnosis. Looking at the example in Table 1: Redesigning the cluttered homepage might help in the short term, but without understanding the root cause (for example, poor information architecture), the homepage is bound to return to its cluttered state in no time. Similar to cleaning the house of a person who has been hoarding, you will only be addressing the surface symptoms without addressing the underlying issue (for example, depression).

SOAP notes will help your team understand the complete picture that led to your diagnosis and treatment plan. Although issue trackers hold a lot of rich information, they are often detailed and in the weeds. It’s easy for the team to get fixated on small issues and technical constraints without understanding the bigger picture of the diagnosis and why they need to address the root cause, not just individual symptoms. In addition, your assessment, similar to a mental health diagnosis, can provide a severity rating to give additional context and help the team to prioritize treatment approaches to overarching issues rather than individual bugs.

Similarly, recommendations listed in a log (independent of identifying the issues) lack the contextual evidence needed to make sure that the right set of issues gets addressed, or that the correct solution is chosen. Providing SOAP notes to stakeholders allows them to see the big picture (assessment and treatment plan) and details (subjective and objective notes) at the same time. It’s a complete story. I recommend one SOAP note per UX issue so that you can succinctly communicate the main issues to your team and prioritize next steps for treatment.

Creating a Diagnostic and Treatment Manual for Common UX Issues

Another useful therapeutic method that could benefit UX professionals is the creation of a manual for common user problems. You can use your SOAP notes across projects and compile them into diagnostic categories to get started on building your manual. This is not meant to be a one-size-fits-all diagnostic and treatment manual, but rather a way to organize knowledge that you have accumulated from different projects in a way that you can refer back to easily.

As a psychotherapist, I used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR), a manual of mental health diagnoses and treatment suggestions, to help select the proper diagnoses and treatments for my clients. It was a starting place, but it was not the final word on what was going to work for that particular client. Similar to people, all websites/applications/products are different and deserve to be treated as such.

In therapy, treatment plans can include various types of therapeutic approaches (cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychoanalysis, etc.), medications, therapy that looks beyond the individual (for example, couples or group therapy), and further treatment by recommended specialists.

As a UX professional, similar to being a therapist, you may have a variety of treatment options available. Understanding the diagnosis for a design issue may help you select the appropriate treatment plan. You may want to create a manual of common user issues to help identify causes of user confusion and build a list of corresponding solutions that have worked in the past. This way you are not starting from square one on each project, and you have a reference guide that you and your UX team can tap into when you are struggling to come up with a diagnosis or treatment plan for an issue.

Table 2 demonstrates what an entry in a hypothetical “User Issues Diagnostic Manual” might look like. As you can see, user issues, diagnostic criteria (in other words, evidence), and treatment ideas are all in one place. Your manual might include primary topics such as Navigation, Design and Layout, Content and Terminology, and System Feedback (and much more!). This manual is designed to connect these user research elements to increase your skills as a UX practitioner and provide a framework to collect knowledge across projects in a common language for you and your team.

Table 2. Example diagnosis in a hypothetical User Issues Diagnostic Manual.

| Overly complex navigation

|

Examples

Flyout menus on mobile that go off the screen Multi-level deep navigation that does not provide a scent of information Icon menus without words |

| Criteria for overly complex navigation

Users report that navigation is “not intuitive” and difficult to use Users are unable to complete tasks requiring them to use the navigation elements Top navigation elements are rarely used for navigating the site |

|

| Assessment

Rule out content-related issues before making diagnosis Diagnosis has varying levels of severity: Mild – Minor or cosmetic Moderate – Negatively impacts UX Severe – Prevents task completion |

|

| Treatment Plan

Review website analytics and usability study findings to discover which navigations were easy vs. difficult to use Conduct a comparative review to explore navigation elements on websites with similar content Explore root causes for complex navigation: who built it and why? Business decision? Development decision? |

|

| Recommendations

Must meet user, business, and technical requirements while addressing the usability issue Recommendations will be specific to each unique site, but you can compile a list here to see what you have recommended in the past |

A Final Thought

Using SOAP notes to communicate UX issues with your team and stakeholders will help you to show evidence for your diagnoses and treatment recommendations. Compiling these notes in a manual, organized by categories, will allow your team to build a cross-project reference guide. You can then compare the severity of issues from one project to the next, refer to past treatment recommendations, and ultimately, create diagnostic criteria so you can improve your ability to accurately diagnose the root cause of UX issues.

[bluebox]

More Reading

Being a UXer: It’s A Lot Like Being a Therapist. – Lindsey Arnold, User Experience Magazine

SOAP note entry in Wikipedia.

[/bluebox]