I have always been enthusiastic about people; it’s exciting to see how everyone is different, from what inspires them to what they dislike, to their individual personal preferences. As a designer, it’s my job to learn about this and find ways to solve problems or improve their daily lives. As designers, we cater to users’ needs, or so we think. Yet we often neglect a significant portion of users, particularly those who are underserved. Our personas represent our ideal users, not the true representation of all users. What about users with cognitive and physical disabilities? Or those with visual impairments, who are elderly, or have speech differences? Are products and services tailored to their needs as well?

Technological advancements, including the rise of AI, are changing the way we interact with products and services. But as a result, we are leaving a significant portion of users behind. Imagine this persona: Emma, a brilliant programmer with ADHD, struggles with apps that overwhelm her with notifications and flashy graphics. Jamal, who has dyslexia, faces a wall of tiny, low-contrast text every time he must fill out online governmental forms. And Mrs. Chen, an elderly immigrant, is completely confused by the cultural references and metaphors that digital designers take for granted. These aren’t edge cases; these personas represent millions of people who are neurologically diverse or come from backgrounds that aren’t considered when companies design products and services.

When used correctly, AI can make products more inclusive. For example, AI can identify when a user needs a simpler layout, and it can remove clutter for users with ADHD. It can rewrite complex text into plain language to help people with dyslexia. It can translate confusing cultural references or provide voice guidance for people who need it. Done well, AI can turn one-size-fits-all products into experiences that adapt to each person’s needs.

Figure 1: A Zoom meeting with diverse participants (credit: Windows on Unsplash).

What Makes UX Neuroadaptive?

In the mid-2000s, German scientist Dr. Thorsten Zander began exploring technology that could read brain signals and automatically adapt to a user’s needs. Rather than relying on a mouse or keyboard, his vision was for a computer that would observe your brain activity and adjust itself based on what it detected.

By 2011, Zander’s team had created systems capable of monitoring brain activity during everyday computer tasks. In 2016, they officially coined the term “neuroadaptive technology” and demonstrated a milestone moment: moving a cursor on a screen purely through brain signals, no hands required.

As Fairclough and Zander (2022) describe, neuroadaptive technology interprets brain signals to understand what a person needs or intends, allowing computers to respond in ways far beyond traditional input methods. That is, instead of clicking, typing, or tapping, a neuroadaptive system reads users’ brain activity through devices such as EEG headbands or fNIRS sensors, and it uses the readings as implicit input. The interface, content, or timing can change automatically based on how engaged, stressed, or confused the user is.

Neuroadaptive AI combines real-time psychophysiological assessment, neuroscience insights, and AI to deliver systems that adapt instantly to a user’s cognitive and emotional state. Rather than offering one-size-fits-all experiences, these interfaces learn and respond uniquely to each person.

Here are a few examples of neuroadaptive design in action:

Cognitive load balancing: The German Aerospace Center and NASA have tested flight dashboards that dim, simplify, or postpone non-critical alerts when the EEG shows the pilot is under heavy cognitive load.

Adaptive learning platforms: Experimental e-learning tools can change the pace or difficulty of lessons when a student’s brain signals show fatigue or loss of focus.

Neuroadaptive gaming: Games (monitored with brain sensors) can increase or decrease difficulty based on how immersed or stressed the player is.

Software and mobile apps: A website notices a user repeatedly scrolling back and forth, so it simplifies its navigation. Or an app detects a user struggling with a form and automatically offers extra guidance.

A neuroadaptive design approach broadens the scope of inclusive design. Neuroadaptive UX can benefit people with formal neurodivergent diagnoses and those with cognitive impairments, learning differences, or sensory processing challenges. Poor UX can frustrate these users, making them feel excluded, which can result in damaging trust or preventing task completion altogether. By integrating neuroadaptive principles, designers can address a broader range of cognitive and sensory needs, creating digital experiences that are more intuitive, supportive, and inclusive for everyone.

Figure 2: A woman uses heart-rate sensors and a tablet (credit: Mindfield on Unsplash).

Key Principles of Neuroadaptive UX Design

The design of effective neuroadaptive user experiences hinges on several key principles.

Personalization and Customization

The concepts of personalization and customization are commonly used in persuasive and behavioral tech, where these important principles allow users to tailor the interface to their unique needs and preferences. For digital products, personalization and customization can include adjusting web and mobile components such as font sizes, light or dark modes, and contrast levels, as well as more nuanced settings for audio, visual, and even tactile feedback. Furthermore, interfaces can include customizable layouts and navigation options, allowing users to interact with the digital environment in ways that are suited to their cognitive abilities. The use of AI-driven adaptations, which learn from user interaction patterns to provide smart text simplification or predictive search tools, can further improve customization. This level of customization empowers users, giving them a critical sense of control over their digital experience, which is especially useful for people who see and process information differently.

Neuroadaptive UX moves beyond static personalization to systems that respond in real time to a user’s cognitive or emotional state. Instead of relying solely on saved settings and past behavior, neuroadaptive interfaces can adjust—moment by moment—complexity, pacing, modality, and feedback as conditions change. For example, a system can temporarily simplify a screen during high cognitive load, delay notifications until attention returns, or switch from visual to audio cues when overload is detected. The focus shifts towards understanding and responding to spontaneous reactions and implicit interactions, creating a more natural and intuitive digital environment. This dynamic, responsive aspect of neuroadaptive UX holds immense potential to create digital experiences that are more effective, more empathetic, and human-centered, which is particularly helpful to individuals with neurological differences or other challenges who may find traditional, static interfaces difficult to navigate or engage with.

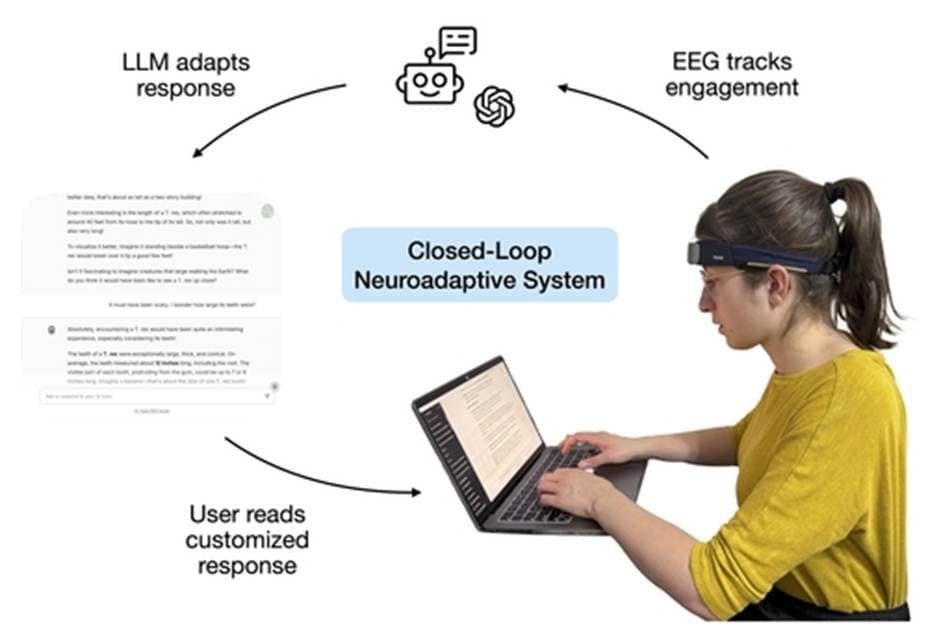

Figure 3: A user interacts with an LLM as a closed-loop neuroadaptive system (credit Dünya Baradari).

Sensory Considerations

Sensory cues are another critical aspect of neuroadaptive design. Interfaces should be carefully designed to reduce sensory overload. But how? A design can reduce load by limiting the use of bright, highly saturated colors, distracting or flashing animations, excessive or abrupt auditory cues, and visually cluttered layouts. Product teams can use calming color palettes, clear and legible typography, and ample white space. All of these design elements are essential for creating a more comfortable visual environment. Furthermore, providing users direct control over sensory aspects, such as the ability to adjust sound levels, turn animations on and off, and modify visual stimuli, is critical for accommodating diverse sensory preferences and sensitivities.

Reducing Cognitive Effort in Neuroadaptive Interfaces

The whole point of neuroadaptive interfaces is to reduce the mental effort required for users to interact with them. This can be achieved through strategies such as conducting research with diverse users, then implementing structured and intuitive navigation.

Testing is crucial to understanding where users struggle.

Recruiting the right participants is key to effectively testing a neuroadaptive interface. Start by defining your target user groups, including typical users as well as those with different abilities or experiences. Use direct outreach, online platforms, and partnerships with relevant organizations to ensure diversity. For usability testing, 5-8 participants per group often yield the most insights, whereas 15-30 participants per group can provide meaningful quantitative data. Include users with a variety of abilities, ages, and technical familiarity, making accommodations for accessibility where needed.

Breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps with timely feedback at each stage helps reduce cognitive strain. Instructions should be provided in a step-by-step and clear manner. Content can be presented in plain language, as clear and concise as possible, and design patterns should be consistent throughout the interface.

By combining structured research with inclusive participant recruitment and thoughtful design, neuroadaptive interfaces can become truly user-centered and reduce cognitive load, making interactions more intuitive for everyone.

Transparency and User Control in Neuroadaptive UX

In neuroadaptive UX, interfaces adapt in real time based on a user’s brain activity or cognitive state, often without explicit input. This creates a unique ethical responsibility: Users must understand when their neural data is being used and how the system is adjusting in response. Providing clear options to opt in or out of neuroadaptive features and allowing users to set the level of adaptation is essential. For example, a learning app that changes difficulty based on attention levels, or a dashboard that modifies alerts according to cognitive load, should clearly communicate these adaptations. This transparency not only fosters trust but also ensures users feel in control of a system that responds to their neural signals.

Real-World Examples That Make a Difference

Neuroadaptive UX has a wide range of possible uses. For example, NASA and the German Aerospace Center have dashboards that can adjust alerts based on pilot cognitive load to improve safety. Research learning platforms can monitor attention and change lesson pacing to keep learners engaged; whereas experimental neuroadaptive games can adapt difficulty or narrative based on players’ emotional and cognitive states.

Thorsten Zander’s BCI™ cursor system demonstrated implicit control directly from brain activity. In healthcare, devices like those from g.tec™ or MindMaze™ can adjust therapy exercises according to patients’ brain signals to improve patient outcomes. Even automotive research has tested driver attention-aware interfaces that modify warnings or semi-autonomous features.

These examples highlight how neuroadaptive UX can respond to users’ internal states to create safer, more inclusive, and highly personalized digital experiences.

Addressing Challenges and Ethical Considerations

In Fairclough and Zander’s 2022 article, “Current research in neuroadaptive technology,” ethics is defined as the moral and professional standards that guide decisions and actions taken during a research project. Ethics define which choices are acceptable and which are unacceptable. Although the implementation of neuroadaptive UX is promising, it also comes with several challenges and ethical issues. Major concerns revolve around users’ privacy, chiefly the collection of their sensitive neurophysiological data and its possible use thereof.

Given the deeply personal nature of sensitive data, designers and developers must handle this information with the utmost care, employing robust data anonymization and encryption techniques in addition to obtaining explicit consent from users for the collection and use of their data. Another important factor in ensuring trust in this system is keeping users well-informed about the means of collecting, analyzing, and using their data to improve their digital experience. Users ought to know what is going on within the system and have control or customization options offered to them to align with their preferences and comfort levels. Ethical frameworks and guidelines need to address these complex issues to ensure the responsible development and deployment of neuroadaptive technologies.

The Future of User Experience: A More Empathetic and Responsive Web

Neuroadaptive UX has the potential to fundamentally reshape the landscape of digital experiences, moving towards a future in which interfaces are highly functional and deeply empathetic, highly responsive, and intelligently matched to the particular and ever-evolving requirements of individual users, which is especially important to those who are neurodivergent or marginalized. This innovative approach will become standard and expected in the creation of user-centric digital environments that seamlessly adapt to a user’s cognitive state, sensory preferences, and individual requirements in real time.

Looking ahead, we can imagine these examples of future applications in neuroadaptive technology.

Smart system: A persona, Linda, is a 70-year-old woman with early-stage dementia who wants to visit her grandchildren on her own. For Linda, using public transport has become confusing; she struggles with small buttons and complex instructions, and she gets lost in the process. Then, a smart system is made just for her. Instead of tapping through apps, she can say, “I want to visit my grandchildren.” The system speaks in a calm voice, gives her step-by-step directions, reminds her when to get off the bus, and adjusts its tone if she seems confused. It even remembers the places she visits often. The technology isn’t just voice control; it is a new kind of tech that understands her needs and helps her stay independent without overwhelming her.

Adaptive learning platform: Educational learning can be adjusted in the complexity of content in real time based on a student’s comprehension, either reducing the language or providing more help when a student is struggling. Platforms can adjust the pace of instruction or suggest breaks by monitoring indicators of attention and fatigue. Additionally, learning paths can be dynamically personalized based on individual learning styles and cognitive strengths, creating a more engaging and effective educational experience.

In conclusion, by moving beyond the inherent limitations of static interfaces, we can embrace the dynamic and responsive capabilities of neuroadaptive systems. We can collectively build a more accessible, equitable, and human-centered digital world for everyone.

Resources

Baradari, Dünya, Nataliya Kosmyna, Oleg Petrov, Roman Kaplun, and Pattie Maes. 2025. “NeuroChat: A Neuroadaptive AI Chatbot for Customizing Learning Experiences.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.07599.

Fairclough, Stephen, and Tobias O. Zander. 2022. Current Research in Neuroadaptive Technology. London: Academic Press.

Nielsen, Jakob. 1994. “Usability Inspection Methods.” In Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’94). New York: ACM.

Resnik, David B. 2020. “What Is Ethics in Research and Why Is It Important?” National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/bioethics/whatis.

Rosala, Miroslav. 2021. “How Many Participants for a UX Interview?” Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/interview-sample-size/.

Rubin, Jeffrey, and Dana Chisnell. 2008. Handbook of Usability Testing: How to Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective Tests. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley.

Jude Ejike is a user experience designer with a proven track record of creating intuitive, scalable, and inclusive digital products across fintech, healthcare, education, and e-commerce. He specializes in combining user research, behavioral science, and AI-driven insights to design experiences that reduce user friction, increase engagement, and drive meaningful outcomes aligned with business goals. Currently, he is exploring how AI can be leveraged to power neuroadaptive systems and how technology can dynamically respond to users’ cognitive states for more personalized, responsive experiences.

User Experience Magazine › Forums › Beyond the Interface: Exploring Neuroadaptive UX for Neurodiverse and Marginalized Users