In the software business, there are two separate yet equally important methods of product development input: voice of the customer (VOC), which investigates what customers have to say, and user research, which seeks to learn how users behave. These are their stories. (chung-chung)

Although the comparison to TV’s Law & Order may be dated, the phrase “separate yet equally important” is a great way to describe the relationship between user and VOC research. Of course, rather than working to bring justice to all parties, VOC and user research work together to help develop useful products that meet the customer’s business needs by meeting the needs of the user. While understanding the end user is, of course, central to the user experience discipline, user experience professionals should participate in voice of customer whenever possible in order to extend that deep understanding to the customer, as well.

The Value of Asking Customers

Talking to customers (the people who stand in for an organization buying the product) about their needs is typically a responsibility of sales and of product management, and is influential within organizations. Many of us have witnessed user-centered enhancements deprioritized in favor of customer requests, which can be painful for us and for users themselves. At the same time, user experience professionals frequently undervalue research conducted with the people who represent customer organizations in a business capacity, and can miss an opportunity to leverage insight into customer culture, goals, and strategy to drive a product—new or existing—toward greater success.

Talking about technology innovation, people throw around an adage attributed to Henry Ford: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Sometimes we use this anecdote to imply that people only have superficial insight into their own needs; they ask for a specific solution (horses) rather than describing their need (a way to get farther faster).

Even if customers do jump directly to a solution, asking them about their experiences and goals is still worthwhile. “Faster horses” shouldn’t be the end of the conversation. Instead, it’s an opportunity to uncover a need. The same goes for customers who request “a spreadsheet emailed to me more often,” but would be even happier to see the same data in real time so that management decisions are based on the most current information. Whether the customer request is faster distance travel or more current data, there’s significant value for a user experience professional in participating in the conversation.

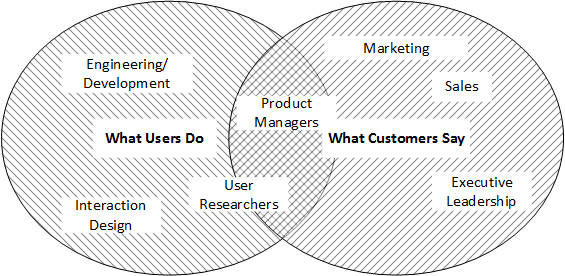

While customers are rarely experts on the needs of their users, they can tell you things about their businesses, their goals, and how they think about their problems—insights that research with end users may not provide. The two approaches complement one another: user research tells us how users behave; VOC tells us what customers want. Together, they can be incredibly powerful. So, how do they fit together?

Problems Solved

User research, in its diverse forms, can illuminate characteristics and behavior of a given set of users. By understanding users’ goals, we can design a product to help achieve them. The activities that help us build that empathy are very different from the ones that help us understand customers, and may be more blunt. However, VOC can tell you about your customer organization’s goals, as well as which problems are bubbling up to management. By talking to managers or executives, you can learn a lot about how the company thinks about its problems and users; this can be helpful in understanding feature prioritization, even if that work is outside of your purview.

VOC is at its most useful when focused on problems and goals. I’ve seen firsthand that the more granular the feedback from a customer on an existing or prototype product, the less beneficial it is from a product design point of view. As a designer, I cringe when informed that we’re going to be putting a button “there” because a strategic customer has requested it. As a product manager, if I’m told that a customer wants a specific solution to a problem, I try to return the conversation to the problem itself, so we can explore alternatives. If there’s a clear cost to user experience associated with developing a feature as requested, it’s sometimes possible to propose and sell the customer an alternative. Otherwise, it’s worth keeping in mind that developing and delivering a specific requested feature can be a valuable relationship builder. Relationship building may not be a core user experience responsibility, but it is a net good for the project.

Conducting VOC Research

Timing

User research takes place across the lifecycle of a product, from driving ideation to validating enhancements (see Figure 1). Conversely, VOC tends to inform product strategy and direction more than user research itself does, although neither is exclusive. In other words, VOC’s best use is toward the beginning of the lifecycle. Involving customers at the point of ideation allows you to understand and prioritize their needs up-front, making sure that a new product or major enhancement is advancing customers’ business needs and goals. Involving customers in feature prioritization can be particularly beneficial. VOC during design phases can yield feedback that’s not representative of actual users, so proceed with caution. If the customer isn’t also an end user, his input will be of limited value, and he is likely to share it anyway.

Researchers and Participants

For most types of user testing, most if not all, of the people conducting the testing will be from the user experience team; VOC researchers (or research observers) typically include a wider range of roles. These include executive leadership, marketing, customer support, a sales function, and product management. Ideally, user experience should be involved, as well, in order to build a deeper empathy toward the customer. Participants can be people who contributed to the buying decision, as well as people who use the product regularly. In fact, a very broad spectrum of roles may participate, depending on a number of factors including the size of the customer organization, the purpose of the discussion, and the tone of the relationship between the organizations.

In many business-to-business organizations, recruiting for and scheduling a VOC session is performed by someone in a sales or product management role. I’ve found that when I’ve worked closely with the account manager or product manager to screen participants for their relevance to the topic and develop the agenda, my experience has been positive. I was reminded how important this collaboration is when a recent VOC session fell short of my expectations. I was hoping to understand a customer’s specific frustrations (both usability and business-related) with software licensing. The participants represented a wide range of roles in manufacturing, from IT management to machine operators to quality assurance. Although the meeting was cordial and interesting, the wide array of experiences prevented us from going very deep during the allotted time. Next time I’m in a similar situation, I’ll work with my colleague in sales to choose one production area at a time.

Tools

The universe of tools for user research is a large one. There are broader research platforms, specific point solutions for individual research methods, pencil-and-paper approaches, and many more. Because VOC research is heavily based on conversation, tools can be less specialized, like video recordings and various documentation methods. However, a few very specialized tools can give a VOC gathering a boost. One particularly useful tool is a web portal that allows customers to enter issues or enhancements and to vote on those entered by other customers. Many enterprise customer relationship management (CRM) platforms like Salesforce.com, SAP, and Oracle have versions of this functionality, but I’m most familiar with the Salesforce.com tool, which allows representatives of customers to enter requests for fixes, features, and enhancements. At one accounting software company that implemented this portal with a voting feature, customers “voted up” a defect which, although it was a known issue, had been bouncing along without a fix for several years. As the product managers watched the number of votes soar, we realized the gravity of the situation and were able to prioritize and rapidly deliver a fix. The feature in question no longer required a workaround, and a specific workflow was much easier to complete.

Conclusion

Viewed through a user experience lens, voice of the customer research has its weaknesses in an enterprise business model, particularly that the users themselves aren’t represented. Used well, however, VOC can be a powerful tool to develop deep understanding of the customer’s business goals and challenges, more context for the roles we see users playing, and insight into the customer’s guidance around product strategy. A product will only succeed in the market through thorough understanding of both the end user and customer. User experience professionals have an opportunity to drive that success further by bringing their skills—their unique empathy, listening, and analysis—to VOC research.