There is a general, yet misleading, notion that poor signage and map design in public spaces is the cause of the difficulty people have navigating within these environments. Most of the time, it is poor planning and design of the space in the first place that causes the wayfinding problems.

While wayfinding aids are important, the clarity of the spatial structure itself forms a “visual language” that communicates with people. Wayfinding design must be approached in a holistic manner that includes the legibility and readability of spatial structure as well as wayfinding aids.

Visual Language of Public Spaces

One often hears directions such as “Go down this way and turn left when you see the big tree; the place you want to go is next to the post office,” rather than “The place that you are looking for is 200 metres southwest of here.” Increasingly, new media such as the Internet and GPS devices are using landmarks as visual clues instead of relying entirely on maps. The growing popularity of this approach is evidence that people are interacting with the built environment through its visual form. More importantly, people are learning about the physical environment through experience at eye-level, as opposed to the traditional bird’s-eye view provided by geographical maps and measurements.

Understanding visual language in public spaces is critical in the planning and design of shopping centers. In a research project I was involved in, the team investigated the issues of the elderly navigating in large-scale shopping malls in Perth, Western Australia. We found that the elderly (and likely others) require distinctive landmarks to help solve wayfinding tasks. However, current shopping malls often lack prominent landmarks. The similarity of architectural configuration and spatial structure at junctions make it difficult to navigate and mentally construct landmarks. This situation was found especially in radially structured shopping malls that have multiple wings and junctions, where all walkways are similar.

Although our research focused on the elderly, the outcome can be extended to the broader public. Our findings strongly suggest that wayfinding capabilities are dependant on the visual aspects of spatial structure.

Landmarks and Wayfinding

The distinctiveness of landmarks is also important to urban environments. Many modern cities are now moving from generic and monotonous streetscapes to vibrant public spaces with distinguishing architecture. The vibrancy not only creates an identity for the place, but also creates visual clues that help people understand the physical environment more clearly.

Melbourne, Australia, for example, has dominant landmarks that help visitors to construct a clear, memorable image, which, in turn, helps them navigate within the city. One prominent landmark is Federation Square located at the city centre. Built above the railway lines, it projects an interesting configuration that catches people’s attention. Since its completion in 2002, it has become a cultural and tourist center for the city. From a wayfinding perspective, its striking visual configuration and strategic location have made it a starting point for exploring Melbourne. From the square one can see other important destinations, such as Flinders Street train station, the Art Centre, and shopping strips. The strategic planning and design of the square have created a visual experience that helps ease wayfinding problems in the city.

Other Melbourne landmarks also function as visual clues. The city not only constructs new and contemporary buildings, but maintains and refurbishes old heritage buildings that help to ensure the “legibility” of the cityscape.

These buildings were built on grid-structured streets. There are typically concerns that a grid structure will disorient people because every street corner will look similar. Melbourne has overcome this with distinctive landmarks that function as visual clues.

Signage or Built Space

It is impossible for wayfinding aids, such as signs, to function independently. In fact, over-design of wayfinding aids will only cause more confusion and visual pollution. The Maritime Museum in Fremantle, Western Australia, provides an example of the importance of legibility of space over signage. As part of my Ph.D. research, I studied the ways people relate map information to the built environment and vice versa. Participants used a given map to find four destinations in Fremantle, one of which was the Maritime Museum.

I found that while most participants could identify the location on maps, about 80 percent had trouble finding the museum in person. They were confused in the physical environment because they could not see the building and there were many other confusing elements in the visual landscape. For example:

- The museum is not visible from the city centre because it is hidden behind rows of sheds. Participants were mainly confused when they came to the junction in front of the shed buildings. Even though some could identify the tip of the museum’s roof behind the other buildings, the roads in front of the sheds branch in directions pointing away from the museum.

- The museum is surrounded by other important landmarks such as the Motor Museum. Realizing the difficulty visitors had accessing the Maritime Museum, signs were put up to provide wayfinding guidance. The sign-age system included not just directions to the Museum, but also signs warning visitors of the wrong way to the museum, to try to direct them away from that path.

However, the overabundance of signs led to participants getting so confused that they started to walk in circles, trying to decide which sign to follow. Some actually took a path that a sign told them not to follow. In this case, the over-design of signage made the experience more confusing. The real issue was the poor legibility of the location of the museum, which was an urban planning and design mistake, not one of signage.

When Space is Already Built

What do you do in a case like this, where the building is already built and installing more sign-age would not help to improve the people-spatial experience? Possible solutions include:

- Planning and building distinctive landmarks in between likely departure points and the intended destination. This helps people relate the destination with other landmarks and construct a more comprehensive mental image of the environment as a whole. It is most effective to let people understand the physical environment in their own way. Everyone constructs different meanings from the same space. For example, a religious person would remember churches or temples as landmarks, while another who likes to party would remember where the clubs and pubs are.

- Providing transportation such as a shuttle bus to the intended destination. It is often easier to bring people to the place rather than let them struggle to find their own way. In the case of Fremantle Maritime Museum, the council has taken this approach.

User Control in Wayfinding in Public Spaces

Another common issue in public spaces is the attempt to structure space in a linear way. This is where the authority tries to tackle wayfinding by controlling people’s movement. These situations can often be found in old buildings or buildings that have been converted from an enclosed space to public access.

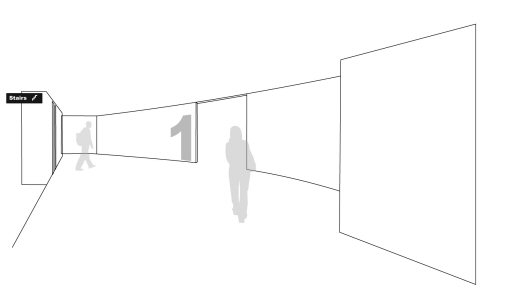

In Figure 3, narrow walkways try to lead people from one place to another in a linear manner. The legibility and visibility of spatial structure is limited to just the path in front of the user. But the parts of the space that they need to access are not always logically accessed in a linear way.

Very often, the response to these wayfinding problems is to post signs and maps. Rarely do management realize that the actual problem is the maze-like walkways that allow only limited spatial legibility. It is critical to understand that it is difficult for people to navigate when they cannot learn about the surrounding environment as a whole.

It is often more sensible to treat the problem as a structural re-design challenge. A possible solution is to open up the tight space into a legible and more welcoming space (Figure 4). In this way, people can visually access the built space as a whole and construct a clearer mental map.

An advantage of this strategy is that it reduces visual pollution of overcrowded wayfinding aids, while tackling the root of the wayfinding problem. Obviously, the restructuring is limited to the basic structure of the built space. It is far preferable to take the legibility of the spatial structure into consideration at the planning and design stage. It is much more difficult and costly to alter major architectural structures than to plan carefully in the first place.

Conclusion

The legibility of spatial structures is important in order for people to understand the surrounding environment. Wayfinding aids are important, functioning as visual support to help solve wayfinding tasks, but poor wayfinding aids are not typically the main cause of navigational problems. To ensure navigation-friendly public spaces, careful thought must be given to the spatial planning and design from the start of any project. A clear and legible space with minimal wayfinding aids is always easier to navigate than a complex environment with lots of signs and maps. Wayfinding design must be a collaboration between urban planners, urban/architectural designers, and visual communication designers.