According to a report by Alzheimer’s Disease International, the global population of people with dementia is now about 46 million and is expected to grow to 131.5 million by 2050. It is also estimated that most of these people will live in Asia. The number of elderly patients with dementia in Taiwan has also increased, and Taiwan lacks well-designed rehabilitation activities for these people. This topic was selected for further design development because the existing number of professional therapists is insufficient to provide the number of treatments required by this population. It was discovered that the existing activities are mostly conducted using paper-made rehabilitation tools. Patients rely on a therapist for guidance and it cannot be conducted by themselves. These tools have other drawbacks, including:

- Inflexible content

- Not linking directly to the patients’ life experience

- A limited ability to provide useful stimulation for the patient

Figure 2 shows examples of current paper-made rehabilitation activity tools.

In collaboration with therapists and using information and communication technology, a new software-based group rehabilitation activity was designed. The preliminary design included:

- Rich and varied sound stimulation

- Personalized rehabilitation content

- A clear information architecture and interaction

- Visual stimulation to enhance attention during the activity

Designing the First Version of the Prototype

Design Concept and Process

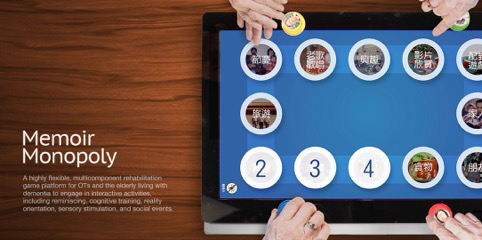

In the first version of the prototype, a highly flexible data collection process was established using a group game module on an iPad. This process was based on the paper-tool monopoly game that rehabilitation centers use to conduct group activities. Patients, family members, and caregivers were asked to provide personalized content for the patients such as photos, songs, and videos. Before starting the activity, the activity leader loaded the content into the game employing four iPads to create a unique monopoly “game map.” The game included one caregiver and five participants. The participants took turns throwing the dice and moving the touch-sensitive pieces on the game map to play with different games. The map included four different game blocks:

- Reminiscence photos

- Music and videos

- Question cards

- A pog game

Initially, a multi-disciplinary design process was conducted to develop a variety of prototypes that were then reviewed with therapists to ensure that the visual elements and interaction design would be appropriate and accepted by the participants (see Figure 3).

Prototyping and Testing

The first prototype was tested with two groups. However, some problems were encountered due to cognitive and emotional issues of the participants. Conducting short-term testing with unfamiliar people, and introducing new activities that are not part of the regular routine can result in emotional problems. Understanding the feelings when dementia patients interview themselves is difficult. Since the therapist who participated in the testing had years of experience leading activities and the caregivers were familiar with the patients, it was determined that the caregiver’s observation of the patient participants would be more reliable. The therapist leading the process was observed and later interviewed to understand the participants’ reaction. Figure 4 shows participants testing the first version of the activity game prototype.

Extending the testing a week provided the opportunity to develop a better relationship with the participants before the formal testing began. Completing the entire course of testing took four to six weeks. This minimized the sense of discomfort experienced by the participants. The participants knew that after testing there would be other interesting activities to participate in based on the recommendations from the therapist.

The testing revealed that personalized content encouraged the participants to tell more stories and that they were more likely to achieve the goals of the rehabilitation activity. They were also able to develop social relationships and make new friends with other participants. The interface also made it easier for the therapists to lead the reminiscing activity. However, several problems were identified. First, the participants had difficulty recognizing four iPads as a single complete game map. They tended to interact with them as four individual blocks. Some of the participants thought the iPad in front of them was their own so they would only interact with that iPad. Also, the screen of the iPad was too small. The activity leaders frequently had to move the iPad closer to the participants, turning the conversation into a one-on-one situation which often resulted in the other participants in the group losing focus.

Other drawbacks were identified in the first version of prototypes. For example, too many complicated visual patterns were used. The assumption was that these visual designs would be familiar to the participants and enhance their interest, but they actually resulted in confusion for participants with reduced cognitive ability who were unable to distinguish between a decoration and an interactive spot. There was also too much information on the screen, including a hint box, a light, and a direction clue. This was too much information and made the activity too complicated. Participants did not know what to do next and it slowed the activity. This required the therapist to spend more effort and time guiding the participants, adding to the pressure of leading the activity.

Second Version of the Prototype

Based on the test results from the first version of the prototype, the iPads were replaced with a 27-inch touchscreen all-in-one computer. The interface and interaction design was simplified by removing the visual decoration to strengthen the focus spot for the participants. The original activities were ordered as a step-by-step process and an end review was added:

- Warm-up

- Theme activities

- End review

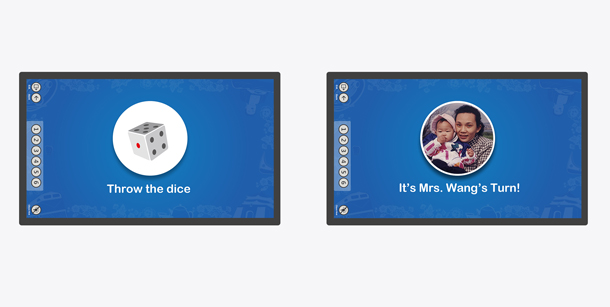

The revised process is shown in Figure 5. The information is displayed on the map as a step-by-step process. First, a color is shown; second, each step is displayed; and last, the map is shown. The participants can follow each step, one thing at a time. Figure 5 shows the information displayed as a step-by-step process.

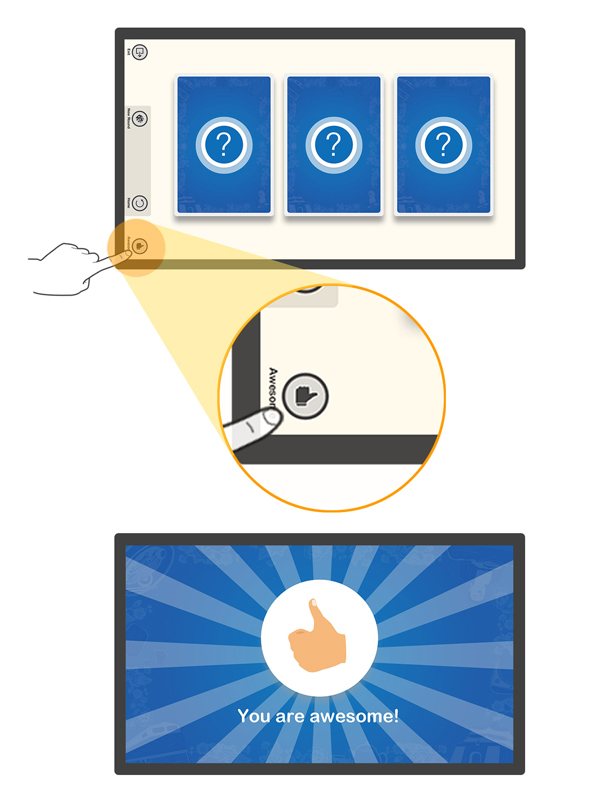

Another important change was to replace the dice interface with photos of the participants as shown in Figure 5. This helped the participants remember what the colors of the dice represent. The participants knew it was their turn when they saw their photo. This saves the therapist time and effort when guiding the activity. A change in the interaction design was also made so that every touchable spot and all buttons were displayed as flashing icons (see Figure 6). After being guided for a few rounds, the participants learned to do this by themselves and even began teaching other participants what to do. This improved the interaction between the group members. The results show that the participants easily learned to play the activity game by themselves and their performance is better than previous activities.

Additional design changes were made to the touch screen to make participants feel less frustrated or afraid to use the touch screen. Participants were observed knocking on buttons or pressing them a long time until there was a reaction on the screen. This is likely from experience using physical buttons, but it may lead to failure using a touch screen. The duration of the touching gesture was adjusted so that a long press or a short knock will result in a successful touch. The gesture trigger was also adjusted to be more sensitive to make it easier to operate.

A separate control panel was developed for the leaders to help them easily guide the whole group. An “align” button let the leaders reset the content to its original location. This helped them find the next object so they could continue to guide the group when the display was cluttered with lots of items (see Figure 9). The participants also responded to encouragement, so an “Awesome” button was added allowing the leaders to display a “You are awesome!” feedback message to encourage participation, pull participants attention back to the activity, boost their confidence, and also attract the attention of other participants in the group (see Figure 10).

From Product Design to Service Design

Testing the second version of the prototype took longer than the first one. Many of the centers and family members were not familiar with the activity process and this would affect the results. Other stakeholders had to be considered in the planning and analysis of the activity to improve the effectiveness of the activity for the therapists and patients, the primary stakeholders. We re-examined the entire event with a service blueprint and customer journey map and found that the “users,” “scenarios,” and “objects” were different when there is only the product. The “users” need to include family members, staff from the centers, and others in the care system, including many different professionals. The activity “scenario” was expanded from just observing the patients during the activity to include time spent before and after the activity. New scenarios were needed for patients living at home as well as those at the care center. Finally, “objects” was expanded to incorporate other items and service processes. Combining this with the current system would provide all the stakeholders with a better experience than previous rehabilitation activities.

A service blueprint was developed that included both tangible and intangible results. Intangible results are noticed when interacting with patents. The patients “feel happy” and have a sense of accomplishment, problem behavior is reduced, and relationships with other patients are established. Intangible results are difficult to notice or can be easily forgotten. There are few tangible results; a few photos at most. Without more tangible results, centers and family members may consider the activity meaningless, even if the patients are happy in the activity. The family members play a critical role since their evaluation of the activities has a direct effect on the evaluation and satisfaction of the centers.

Testing the Service and Developing a Fully Commercialized Service

To include the needs of the centers and family in the process, therapists visited patients twice for an assessment at the beginning of the service. Family members also participated at this stage of the process. They provided the personal content to be used in the activity. During the activity, therapists led a one-hour “Memoir monopoly” activity starting with the “warm-up,” then the “theme activity,” and finally the “end review.” Figure 10 shows patients and family during the “Memoir monopoly” activity. Photographs and videos were taken during the session and the stories shared by patients were recorded. The last step in the process was a “sharing event” conducted with their family present. The group watched films of the activities, listened to the stories, and watched the reaction to the games. Families were given their own story books to keep to preserve the patient’s precious memories. The story books and videos can also show changes in the patient. Therapist advice was also provided to help the families use the activity at home. Figure 11 shows patients and family during a sharing event at a center.

The sharing event had a number of benefits:

- The patients and family review of the process provided encouragement and a sense of accomplishment.

- Family members had an opportunity to talk face-to-face with the therapist and learn more about the rehabilitation results of the patient.

- There was increased trust between family members and the center.

- Other staff members got a better understanding of the patients and learned more about them.

The development team plans to keep in touch with the centers and to continue to collect feedback from the patients, family members, and centers as a reference for future activity development. The service is being tested at four day care centers with up to 200 patients, 8 occupational therapists, 70 family members, and includes more than 100 activities. The results show the positive effect of the activities, obtaining high satisfaction ratings from both the centers and the family members. With the success of the service and the feedback from centers and the family members, we decided to move on and commercialize our service.

With the commercialization, there’s the potential to promote the game in Corporate Social Responsibility(CSR) plans. The cost of the service is significant, which is a burden for many centers. We try to work with companies who operate responsibly to address social issues and want to do social good in Taiwan. We’re working with the companies Aging Society and Aging Caring on plans to continue to bring our service to more centers and patients. The companies sponsor the service to promote their corporate brands, and the patients can then enjoy with the service for free. As the population in Taiwan ages, regulations and concepts need to keep pace so services like this can benefit the aging population.