The recent rollout of healthcare exchange websites in Spanish at the federal and state level illustrates the complexities that arise when developing healthcare websites for Latinos. Many articles have been written about the translation issues with the Affordable Care Act website, CuidadoDeSalud.gov. Low enrollment rates in states with large Latino populations like California, Florida, and Texas suggest that there are cultural messaging issues that need to be addressed. (See Figure 1)

For example, the advertising message “no one can be denied coverage” because of a pre-existing condition is unfamiliar to Latinos who have not had any experience with health insurance. Similarly, heavy promotion of the Covered California enrollment website did not increase enrollment for Latinos because healthcare is considered a personal matter that requires in-person attention.

Cross-Cultural Research Process

Not reflecting cultural values, health beliefs, and linguistic practices in healthcare websites for Spanish-speaking audiences demonstrates the need to move beyond translation alone. In order to successfully reach and connect with Latino users who seek healthcare services or information, it is important to conduct iterative cross-cultural research throughout the development lifecycle. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) has conducted extensive research to identify the user needs of Spanish-speaking communities that have been affected by cancer. NCI findings from the public health literature, user research, web analytics, eye-tracking studies, and usability testing suggest that Latinos have consistent needs related to culture and language that are applicable to all types of health websites, including healthcare exchanges.

The benefits of combining public health and user experience (UX) became apparent when the NCI was developing Spanish language web pages. The initial approach was to use the public health literature to determine what relevant sections of the Cancer.gov website should be translated into Spanish, such as types of cancer common among Latinos. However, findings from previous usability testing of NCI Spanish language content revealed that users perceived this content as “cold” and “impersonal.”

Iterative usability testing of various NCI products (websites, pamphlets) was then conducted to determine how to incorporate these and related findings into NCI Spanish language content. While conducting usability testing with community health workers, promotoras de salud, and Latinos diagnosed with cancer, the following cultural values, beliefs, and language practices were identified:

Cultural Values

- Respeto (Respect): Demonstrating respect towards authority figures, such as doctors.

- Familismo (Family): Recognizing the role families play in healthcare decision-making.

- Confianza (Trust): Creating a warm and friendly approach.

- Personalismo (Personal Connections): Focusing on building a personal connection with users and taking emphasis away from the healthcare institution.

Beliefs

- Fatalismo (Fatalism): Attitudes about diseases and health conditions such as cancer and how cancer treatment is worse than the actual disease. Not having experience with the U.S. healthcare system or using health insurance for the first time could also lead to fatalistic attitudes.

Language Practices

- Monolinguals: Monolingual Spanish-speakers will often compare similar types of websites and content before making a determination about the quality of the translation.

- Bilinguals: Whenever possible, bilingual site visitors compare the English and Spanish versions of websites in an effort to validate translation accuracy.

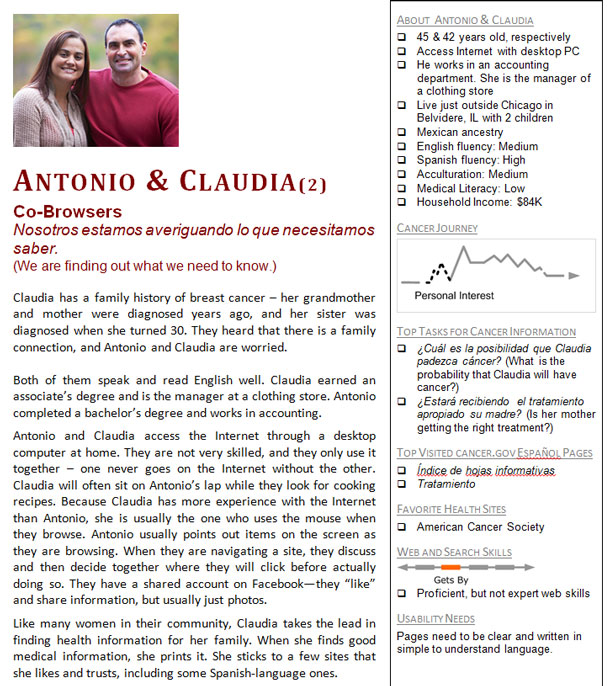

- Co-Browsers: Co-browsing is common among bilingual and monolingual users who depend on each other to identify which pages to visit and navigate and whether the content and translation is accurate.

To address language and cultural needs, we identified basic site functions such as language toggles so that users can navigate between Spanish and English content. Bilingual dictionaries allow monolinguals and bilinguals to look up basic and complex cancer terms in both languages and to hear pronunciations in either language. As a result, co-browsers with different language proficiencies can easily read site content.

As research findings started to include platforms such as mobile and social media, and the reports began to accumulate, it became increasingly difficult for NCI project teams to comprehensively reference users’ needs. Thus, we began the process of building culturally-appropriate Spanish-speaker language personas that could easily be used to reference research findings and to understand Spanish-speaking users throughout the development lifecycle.

Data Used to Build the Personas

The NCI has used personas since 2009 to help stakeholders and site designers better understand their users. Personas have acted as a reliable and realistic representation of key audience segments. To create the Spanish-speaking personas, we worked off existing English-speaking personas that Whitney Quesenbery developed for NCI. This allowed us to focus on the content rather than the overall look and feel of the personas.

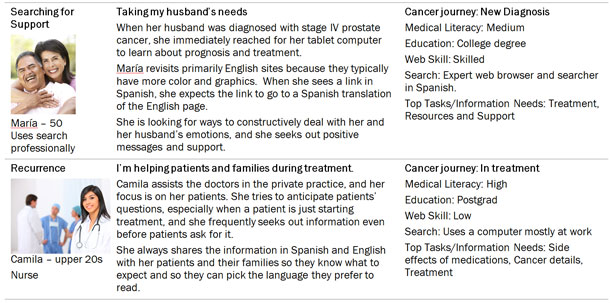

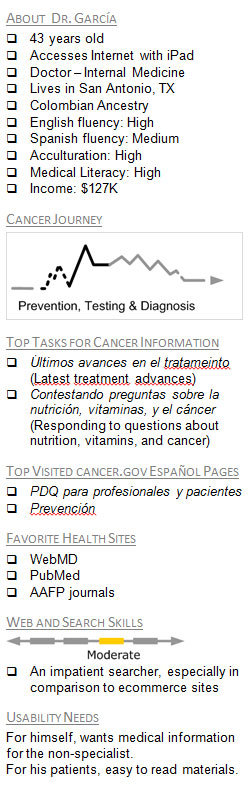

We used prior research and reviewed web analytics to assess what content from the prior English-speaking personas would be relevant for creating a new group of Spanish-speaking personas. Each persona needed to be a realistic representation of target audience segments, so users’ habits, hobbies, health perceptions, language practices, and living situations needed to come from data from actual humans, not our conjectures or best guesses. (See Figure 2)

We examined Google Analytics, which provided us with insight into how users tend to access NCI content. Specifically, we were able to see where on the site actual users accessed content, how long they visited each page, their browser type (such as Firefox, Safari, Chrome), and the type of devices they were using (such as PC, smartphone, tablet).

Pew Research Center and Forrester Research guided our descriptions of the personas’ incomes, housing, and family sizes. For finer-grained details about specific music and entertainment preferences, we used other public data, such as Nielsen’s weekly top ten ratings. These data proved to be vital for the UX team. For example, we were able to ensure Internet behavior matched Google Analytics and that characteristics like income, family size, and education aligned with the cities where actual users lived.

In addition to the rich quantitative data, we solicited qualitative data from key stakeholders who regularly used the English-speaking personas. We organized one-on-one and NCI team meetings and asked about how the existing personas were used and what was missing from them. We asked specifically about Spanish-speaking Cancer.gov users and how those needs differed from English-speaking users. This rich qualitative feedback enabled us to assemble realistic stories that resembled actual Spanish-speaking users of the NCI site and related products.

The Final Product

Each persona contained details about a typical user’s goals and motivations and their background, behavior, and habits, which took up the majority of the page. Following the same layout as the English language personas, the right side of the description included a snapshot summary of information that provided characteristics that matched the audience demographics, Latino ancestry, acculturation and language preference, medical literacy level, co-browsing behaviors, cultural values, typical cancer-related tasks for that persona, and Internet and search skills. (See Figure 3)

Since the Spanish-speaking persona design was identical to the English-speaking personas, it was easy for NCI teams to learn the structure of the personas and quickly reference and compare information. Regardless of the user group, team members could easily find what they were looking for because each persona followed this layout.

In total, we created fourteen personas that included nine from the general public (patients, friends, family, co-browsers, and those interested in cancer information), three healthcare professionals (community health worker, general practitioner, and nurse) and two others (Cancer Information Service Spanish Call Center staff, and patient navigator). The personas were portraits of Spanish-speaking users who seek health and cancer-related information, specifically from Cancer.gov/espanol.

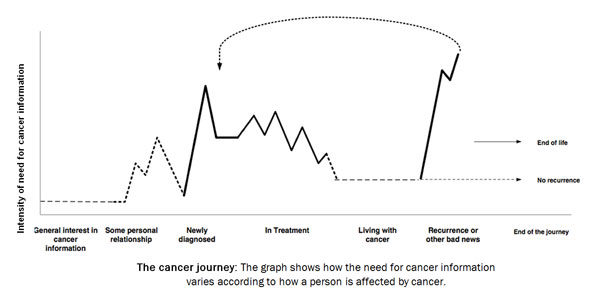

Each was described in terms of where they are in the cancer journey as outlined in the English language personas that were previously created by Quesenbery in 2009. The cancer journey (see Figure 4) is a proposed model that represents the way people personally progress through cancer from a general interest in cancer information, to prevention, diagnosis, caregiving, treatment, survivorship, recurrence, and end of life. Both the English-speaking and Spanish-speaking personas fall within the context of the cancer journey. There is an increased need for information based on how a person is affected by cancer.

Findings Applicable to Other Medical Websites

Although the NCI Spanish-language personas were originally created to represent the needs of Cancer.gov/espanol site visitors, they can also be used for other health websites because language preferences, cultural values, co-browsing behaviors, health beliefs, acculturation levels, and user needs are the same across many types of websites that provide medical or health information.

In the case of healthcare exchange websites, personalismo (building a personal connection) and confianza (trust) can be facilitated by including the perspective of the health consumer who is learning about using health insurance for the first time in their life. An introductory approach may work best, as well as including language toggles. Online bilingual dictionaries can serve as tools to familiarize site visitors with new terms in Spanish and English, such as healthcare exchanges, coverage, insurance card, denial, appeal, and co-pay.

By providing access to site content in Spanish and English, health websites can address the language needs of different users, co-browsers, and families that may demonstrate different levels of language proficiency either in English or Spanish. A perfectly grammatical translation is helpful, but it may completely alienate the intended audience if not presented within the sociocultural context common among Latinos living in the US.

[bluebox]

More Reading

Other articles in User Experience magazine about this topic include:

“Language Barriers in Healthcare Information” by Silvia Inéz Salazar

“¿Habla Español?: Testing and Designing for U.S. Latino Users” by Cliff Anderson

For further information on NCI studies and persona development:

“Design Elements for the Development of Cancer Education Print Materials for a Latina/o Audience.” By P. Buki, S.I. Salazar, and V. Pitton in Health Promotion Practice, October 2009, 10(4), 564-572.

“Storytelling and Narrative” by Whitney Quesenbery, in Pruitt & Adlin, The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design (pp. 520-555). Morgan Kaufmann.

[/bluebox]

[greybox]

Text in Figure 1: Example Personas

Searching for Support: Maria, 50, uses search professionally

“Taking my husband’s needs”

When her husband was diagnosed with stage 1C prostate cancer, she immediately reached for her tablet computer to learn about prognosis and treatment.

Maria revisits primarily English sites because they typically have more color and graphics. When she sees a link in Spanish, she expects the link to go to a Spanish translation of the page.

She is looking for ways to constructively deal with her and her husband’s emotions, and she seeks out messages and positive support.

- Cancer Journey: New diagnosis

- Medical Literacy: Medium

- Education: College degree

- Web Skill: Skilled

- Search: Expert web browser and searcher in Spanish

- Top Tasks/Information Needs: Treatment, resources, and support

Recurrence: Camila, upper 20s Nurse

“I’m helping patients and families during treatment.”

Camila assists the doctors in a private practice, and her focus is on her patients. She tries to anticipate patients’ questions, especially when a patient is just starting treatment, and she frequently seeks out information even before patients ask for it.

She always shares information in Spanish and English with her patients and their families so they know what to expect and so they can pick the language they prefer to read.

- Cancer Journey: In treatment

- Medical Literacy: High

- Education: Postgrad

- Web Skill: Low

- Search: Uses a computer mostly at work

- Top Tasks/Information Needs: Side effects of medications, cancer details, treatment

[/greybox]

[greybox]

Text in Figure 2: Example Demographics

About Dr. García

- 43 years old

- Accesses Internet with iPad

- Doctor of Internal Medicine

- Lives in San Antonio, TX

- Columbian ancestry

- English Fluency: high

- Spanish Fluency: medium

- Acculturation: high

- Medical Literacy: high

- Income: $127K

Cancer Journey: Prevention, Testing & Diagnosis

Top Tasks for Cancer Information:

- Ultimos avances en el tratameinto (Latest treatment advances)

- Contestando preguntas sobre la nutrición, vitaminas, y el cáncer. (Responding to questions about nutrition, vitamins, and cancer.)

Top visited pages on cancer.gov/español:

- PDQ para profesionales y pacientes

- Prevención

Favorite Health Sites:

- WebMD

- PubMed

- AAFP journals

Web and Search Skills: Moderate

- An impatient searcher, especially in comparison to ecommerce sites.

Usability Needs:

- For himself, wants medical information for the non-specialist

- For his patients, easy to read materials.

[/greybox]

美国国家癌症研究所通过研究公众健康档案、用户调查、网络分析、眼动跟踪研究和可用性测试,得出以下结论:拉美裔人群在文化和语言方面具有一致的需求,这 种需求适用于所有类型的健康网站,包括医疗保险交易所。该项目团队开发了西班牙语人物角色,以综合参考用户需求,并让网页开发人员真实地了解目标受众群 体。文章全文为英文版

공공보건기록, 사용자 연구, 웹 분석, 시선 추적 검사 및 사용성 검사에서 나온 미국 국립 암 연구소 연구결과를 보면, 라틴계 미국인들은 보험 거래소를 비롯한 모든 종류의 의료 웹사이트에 적용되는 문화 및 언어 관련 요구가 한결같다는 것을 알 수 있습니다. 프로젝트 팀은 사용자 요구에 대해 폭넓은 참고를 제공하고 웹 개발자들에게 표적 대상에 대한 현실적인 설명을 제시하기 위해 스페인어 페르소나를 개발하였습니다. 전체 기사는 영어로만 제공됩니다.

Dados do U.S. National Cancer Institute (Instituto Norte-Americano do Câncer), obtidos em registros de saúde pública, pesquisa de usuário, web analítica, estudos com rastreamento ocular e testes de usabilidade, sugerem que os latinos possuem necessidades consistentes relacionadas à cultura e ao idioma aplicáveis a todos os tipos de websites de saúde, inclusive trocas entre serviços de saúde . A equipe do projeto desenvolveu personas que falam espanhol para atender amplamente às necessidades de usuários e para oferecer aos desenvolvedores da web representações realistas dos segmentos do público-alvo. O artigo completo está disponível somente em inglês.

米国国立がん研究所による公衆衛生記録、ユーザー調査、ウェブ解析、アイトラッキング調査、ユーザビリティ・テストから得られた結果によると、ラテン系の人は、あらゆる種類の医療情報ウェブサイト(公的医療保険サイトを含む)に共通の、文化および言語関連のニーズを持つことが示されている。このプロジェクトチームは、ユーザーのニーズを俯瞰するためにスペイン語使用者のペルソナを開発し、ウェブ開発者に対象者セグメントをわかりやすく提示した。原文は英語だけになります

Los hallazgos del Instituto Nacional del Cáncer de los Estados Unidos a partir de registros de salud pública, investigación de usuarios, análisis web, estudios de seguimiento visual, y pruebas de usabilidad sugieren que los latinos tienen las mismas necesidades en relación con la cultura y el lenguaje que se aplican a todos los tipos de sitios web de salud, lo que incluye los intercambios de atención médica. El equipo del proyecto desarrolló plantillas Persona de habla hispana para describir exhaustivamente las necesidades de los usuarios y dar a los desarrolladores web representaciones realistas de los segmentos del público objetivo. La versión completa de este artículo está sólo disponible en inglés