Why would I see danger in such useful concepts as low-hanging fruit (easily achieved goals or actions) and a minimal viable product (aka MVP, a product with enough features to attract early adopters and provide feedback for future development)? Well, like all good concepts they need to be applied appropriately—and like many good concepts, they are sometimes inadvertently misused to the point that they become counter-productive. I am not the first person to observe this, of course. Agile Alliance, for example, has detailed common pitfalls relating to an MVP, noting that teams may find themselves falling into the trap of focusing on “minimal” to the detriment of “viable.” Having witnessed this phenomenon and its impact on the design process, I started thinking about how this can happen—and more to the point, how it can be prevented.

My key questions are …

- what, in a project, constitutes the “V” in MVP,

- how does it relate to relevant low-hanging fruit, and

- how can we be sure of creating a truly viable MVP?

I specialize in public sector work where the fallout from getting this wrong is not simply fewer sales—it means people who need access to vital services may be left out in the cold. So, it is the misuse of these concepts within this context that I will focus on. But the possible solution I propose should be of use in all forms of UX design. To start, let’s take a look at some examples where viability has been correctly or incorrectly identified.

Proper Understanding of an MVP and Use of Low-Hanging Fruit

Example 1

I am going to start with an example that does not involve digital design, but clearly illustrates the principles under discussion. A medical research institute has the goal of finding cures for disorders caused by genetic mutations in humans. The institute decides to channel resources into studying a relatively rare genetic disorder rather than a more common one. Why would scientists do this when there are many more people suffering from common disorders? Because they have been able to confirm that this rare disorder is caused by the mutation of one specific gene, while more common genetic disorders involve the interaction of multiple gene mutations. Focusing on the rarer, but more straightforward, genetic disorder (the low-hanging fruit) not only gives the team a higher chance of initial success but, crucially, it will provide the building blocks for addressing disorders caused by more complex genetic mutations. Let’s unpack this.

- Business need: Develop and produce cures for genetic disorders that affect the human population. (As well as producing something good for humanity, this could lead to more research grants and enhance the institute’s reputation in the academic sector).

- User need—research scientists (internal stakeholders) Gain the knowledge necessary to understand and minimize or eradicate the effects of genetic disorders.

- User need—people with genetic disorders (external stakeholders): Gain freedom from the suffering caused by these disorders.

- Key blocker (internal stakeholders): Lack of understanding of how genetic mutations function and how their effects can be minimized or eliminated.

- Key blocker (external stakeholders): Lack of existing cures for the disorders.

In this example, the low-hanging fruit (a rare but simpler mutation) picked by the medical researchers is appropriate. For their work outputs to be minimally viable, they must provide the building blocks that facilitate understanding of the more complex genetic diseases the team has been tasked to conquer. So, although the number of people suffering from the disease is small, working on a cure helps the team understand maladies that affect greater numbers of people. Eventually, both business and end-user needs are satisfied. The initial focus on low-hanging fruit leads directly to gaining later access to harder-to-reach fruit.

Example 2

Now let’s look at an example from the world of digital design. A retailer wants to increase their online sales. They know that the vast majority of consumers interested in buying their specialty products are technologically savvy. Therefore, a solution that makes it easier for tech-savvy potential customers to make online purchases is seen as a useful win. Even though this particular digital solution does not engage shoppers with less sophisticated tech skills, that demographic is not considered vital to the retailer’s business model.

- Business need: Increase sales of specialty products that appeal to tech-savvy consumers.

- User need—website manager/staff (internal stakeholders): Input/update information on the retailer website in a way that facilitates increased sales.

- User need—consumers (external stakeholders): Find and purchase products that meet specific and often complex needs quickly and easily.

- Key blocker (internal stakeholders): Current system is convoluted and difficult to keep up-to-date.

- Key blocker (external stakeholders): It is hard to discover current and sufficiently detailed information about products on the website, which makes it a chore for shoppers to find and buy what they want.

In this example, the low-hanging fruit in the form of potential techie customers is an appropriate focus. The easiest demographic to reach is also the only group that the business is interested in. The MVP merely needs to provide consumers with some form of improved experience on the website. This can be built upon iteratively to further improve the system. It is safe to focus on the low-hanging fruit of end users because the business model does not require engaging the harder-to-reach fruit of less tech-savvy consumers.

In both of these examples, low-hanging fruit and MVPs were identified appropriately. Now let’s look at an example from my domain—the public sector—where those concepts could be used inappropriately.

Improper Understanding of an MVP and Use of Low-Hanging Fruit

Example 3

Let’s say you work in a government department. The business need is to help a vulnerable section of society: people who have spent large chunks of their lives in institutional care and have reached a stage where they are expected to fend for themselves in the world. Services exist to help those in this situation, but the uptake of this support is low. Statistics show that after leaving institutional care, many former clients find themselves drawn into crime, substance abuse, and/or sexual exploitation. So, finding a way to increase usage of available support services is the top goal.

The design project team’s MVP is an app that requires clients leaving an institution to have a smartphone. The app could reach the low-hanging fruit—the least-vulnerable segment of this population—but left those most at risk no better off. There was talk of “somehow” providing smartphones to those with the most chaotic lives. But even if that proved financially feasible, the most vulnerable might understandably be inclined to sell the phones, and they would also be the most likely to have them stolen. However, no time was spent on those issues. The tantalizing prospect of grabbing low-hanging fruit to build something seemed to blind project leaders to the risk of inadvertently excluding the most vulnerable user groups.

Once again let’s break this down.

- Business need: Increase the uptake of existing support services by individuals leaving institutional life. Minimize their chances of being exploited or drawn into anti-social/criminal/dangerous behaviors.

- User need—government support service operatives (internal stakeholders): Establish consistent engagement to provide this population with appropriate support.

- User need—institutional leavers (external stakeholders): Consistent access to relevant support services to improve one’s life chances.

- Key blocker (internal stakeholders): Current system provides no effective way of maintaining engagement with the most vulnerable population.

- Key blocker (external stakeholders): Here is where it gets interesting. For those with chaotic lives, a key blocker is the lack of consistent access to digital devices. For those with more stable lives (e.g., people who have managed to find employment and housing), this is not a key blocker. Their key blocker—also shared with all end-user groups—is the current ineffectual system of communication around support services.

When I became aware of this project, no research had been done with this population because “they’re too difficult to contact.” The group is not impossible to contact; the members of this group just require more effort to contact. The business need is to reach as many vulnerable people leaving institutional care as possible; this is a public service for some of the most at-risk people in society. But research was not done to understand the needs, motivations, and blockers of the most vulnerable individuals. Instead, the design team settled for reaching the low-hanging fruit (less vulnerable individuals) with an MVP that would not provide opportunities to learn how to connect with the most at-risk individuals. Therefore, I would argue that the team was blinded by “M” at the expense of “V.” No matter how beautiful the app and how many wonderful iterations are produced over time, the project will never reach key sections of the end-user group if a smartphone is required to access support.

Ladders vs. Platforms: A Model

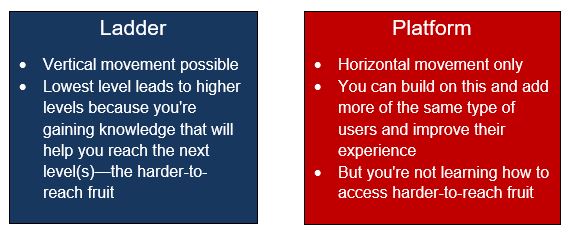

So, how do we ensure that our projects do not fall into this kind of trap? I propose a model that distinguishes between Ladders, which allow for further vertical movement, and Platforms, which only allow for horizontal movement. If you reach your low-hanging fruit via a Ladder, you will be able to continue up to reach higher fruit. But if you reach the low-hanging fruit via a Platform, you will be able to iterate and improve, but only horizontally. You will not reach the higher fruit using this approach.

Going back to our mini case studies, in Example 1 (medical study), the MVP that enabled researchers to reach the low-hanging fruit of a rare but simpler genetic disorder represented the first rung of a Ladder. What is learned at this stage would make it possible to climb higher up the ladder and address more complex genetic disorders.

In Example 2 (the retailer), the MVP of improving the online experience for tech-savvy consumers represented a Platform—the site would not attract less technologically sophisticated customers, but business needs did not extend beyond reaching the low-hanging fruit of techie shoppers.

In Example 3 (support of at-risk population), the proposed MVP also represented a Platform. The business need was to provide support to all those leaving institutional care, with a particular responsibility to the most vulnerable. An MVP that only supported the more stable members of the group and did not produce knowledge aimed at reaching those most at-risk could not be deemed viable.

Choosing an Appropriate MVP Using Ladders and Platforms

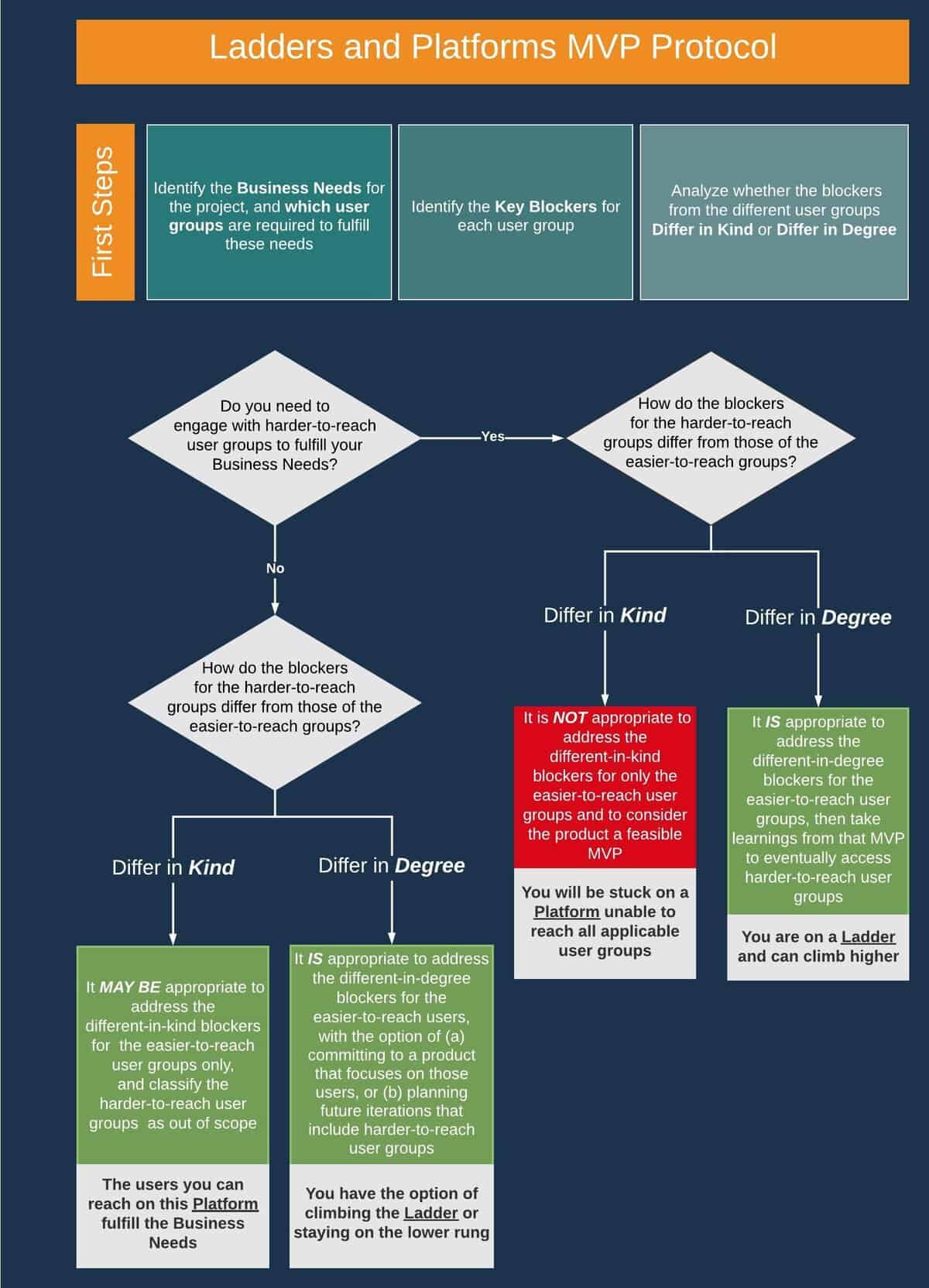

To determine whether a proposed MVP is a Ladder or a Platform—and whether it matters—you can use the following protocol and flowchart.

Protocol

- Identify the business needs for the project, including which end-user groups are necessary to reach to fulfill those needs.

- Identify the key blockers for each category of end user.

- Analyze if/how the blockers from the different user categories interrelate, that is, do they differ in kind (separate and distinct boxes) or do they only differ in degree (points along a continuum)?

After ascertaining if the key blockers faced by end-user groups differ in kind or in degree, the flowchart shown in Figure 1 can be used.

Figure 1. The Ladders and Platforms model for ascertaining truly viable MVPs. (Credit: Donna Baillie)

By following this protocol, users can gain a clearer understanding of

- business needs,

- the needs and blockers of different user groups, and

- of how these first two bullet points intersect.

It asks the questions that help determine what is necessary for MVPs to be truly viable.

I developed the Ladders and Platforms model in response to concerns about MVPs relating to public services projects. But I would be interested to hear if you think this model could be useful in your own specific areas of UX design.