Twenty years ago, Robert Putnam wrote about the rise of “bowling alone,” a metaphor for people participating in activities as individuals instead of groups that can lead to community. This led to the decline in social capital in America. The problem of individual participation as opposed to community building has become an even bigger problem since the invention of smartphones, the Internet as the source of all information, social networking, and asynchronous entertainment. We never need to talk to anyone anymore and it often feels like an imposition when we ask for an answer we know we could find online.

Putnam posited that the decline in social capital is a cause for decline in civic engagement and participation in democracy. If we aren’t engaged socially with the people around us, we don’t have as much incentive to care about what is going on that might affect them. Local elections have low voter turnout in part because people aren’t aware of or engaged in local issues.

In an attempt to chip away at this problem, platforms that attempt to encourage people to engage in civic life with government and local communities have been popping up. But how well do they actually engage people? These platforms are often criticized for producing “slacktivists” who are applying the minimum amount of effort possible and not really effecting change. Several of these platforms were evaluated to see how they work and to determine how well they actually promote civic engagement.

Measuring Civic Engagement

Code for America is an organization that works to increase engagement with local governments by putting together “brigades” of local volunteers to solve local problems using technology. They have developed an Engagement Standard that attempts to measure how well a government enables citizens to engage in civic life.

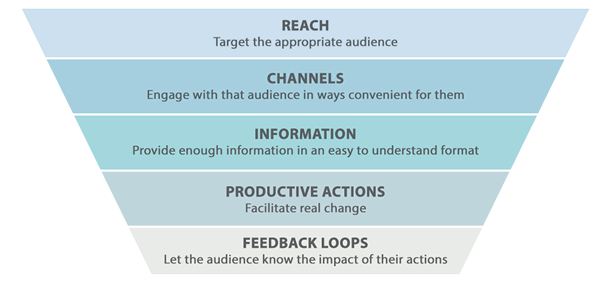

Elements of Code for America’s Engagement Standard include:

- Reach: Defining the constituency you are trying to reach, with an emphasis on identifying those whose voices aren’t already represented.

- Channels: Making use of a diversity of spaces, both online and off, that meet people where they are.

- Information: Providing relevant information that is easy to find and understand, and speak with an authentic voice.

- Productive Actions: Identifying clear, concrete, and meaningful actions residents can take to reach desired outcomes.

- Feedback Loops: Making sure the public understands the productive impact of their participation and that their actions have value.

These elements form a funnel, shown in Figure 1, which starts with reaching the right audience and ends with providing feedback to that audience on the effects of their actions. Platforms that have low engagement tend to get stuck at the top of the funnel and platforms that foster more engagement meet all the standards in the funnel.

Eight Approaches to Civic Engagement

Each of the platforms described below attempts to engage citizens in civic actions. However, each platform has a different approach.

Measuring the Success of Civic Engagement Sites

Reach

How well each platform reaches the right people to engage with an issue.

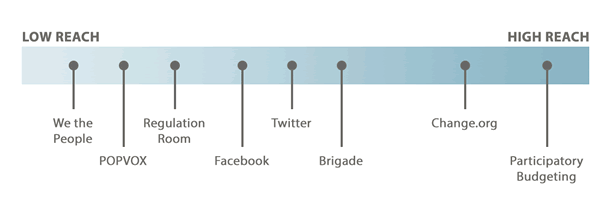

Each of the platforms reviewed has two audiences: the supporters they are trying to reach to support an issue and the audience they need to engage with in order to enact change toward the issue.

Reach (Figure 2) is concerned with how well the platform enables reaching and engaging a large enough base of supporters who care about an issue.

Facebook and Twitter have the ability to reach a lot of people, but have a limited ability to engage the people they are reaching or determine how much those people care about an issue. Twitter is better than Facebook because Twitter users can search for a hashtag related to a specific issue of interest and find tweets related to that issue. Facebook’s privacy controls make it difficult to reach an audience beyond a user’s current “friends,” so posts are rarely shared beyond their friends. Only viral posts, like the Ice Bucket Challenge, generate a large reach on Facebook and these posts spread mostly through tagging, peer pressure, and media attention.

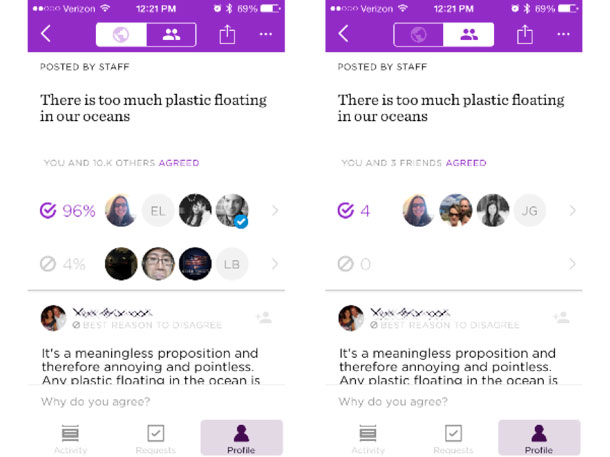

However, the self-selected nature of whom one posts to on Facebook makes it easier to find people who care about the same issues as the poster. Brigade attempts to build on this concept by polling friends imported from social media so that people can find out which issues they have in common and can build a group that supports those issues.

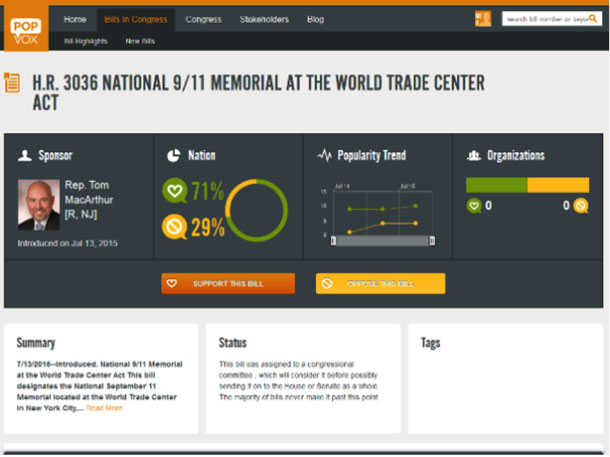

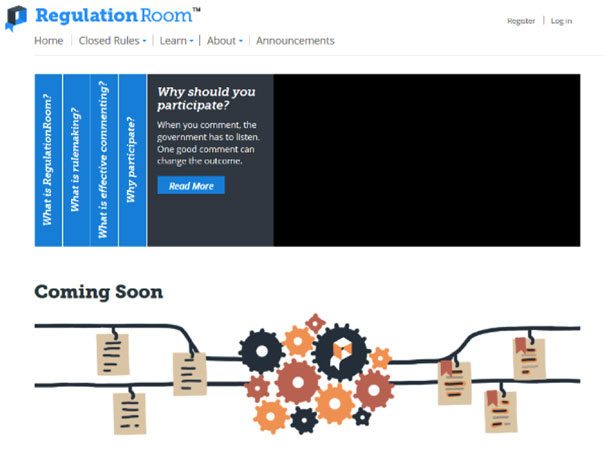

Most of the other platforms use social media as a way to share information about an issue. In particular, Regulation Room tries to tailor its social media posts to find constituents that might be interested in participating in the comment process on the rules it supports. POPVOX also relies on its social media accounts to let followers know what’s going on in Congress that they might be interested in.

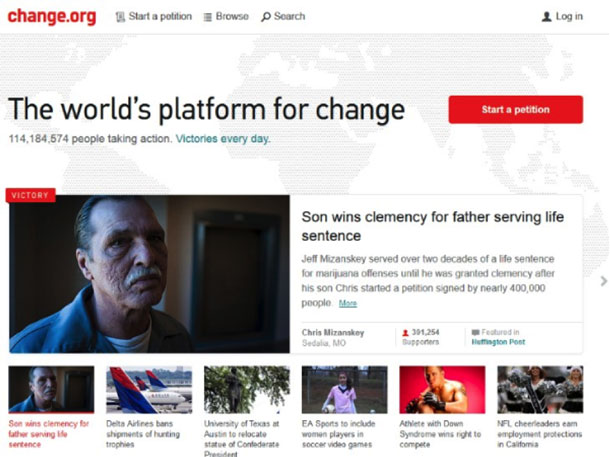

Change.org uses social media to provide a steady stream of updates around petitions that need signatures, and provides updates to petitions as they come in. They also get a lot of media attention, so potential supporters are brought in that way, as well.

Since We the People is affiliated with the White House it doesn’t provide its Twitter account on its site. You have to search for it on Twitter and it is not used to drive reach for petitions that need signatures. It is only used as a feedback mechanism to let people know when a petition has reached the threshold for a response or to post responses.

Participatory Budgeting reaches out to people in the local community to participate. It is a tailored reach to the people who will be affected by the results of the process which results in highly engaged participants.

Channels

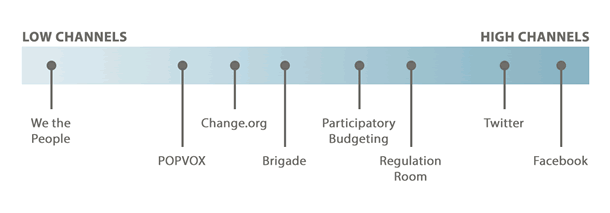

How well each platform engages with people in ways that work for them.

Once a platform has reached people who are interested in supporting an issue, it needs to engage with those supporters where they are (Figure 3). Facebook and Twitter have the most users, somost of the civic engagement platforms use these applications as a way to reach their supporters. POPVOX and Change.org post information and articles about pending legislation and open petitions to their social media accounts to keep people engaged.

Brigade is an exclusively mobile app (at least for the beta version) and imports contacts from social media sites where people are already connected to bring them together around issues. They also post new issues on their Twitter and Facebook accounts, encouraging followers to use Brigade.

We the People uses Twitter to inform followers when a petition has reached enough signatures for a response and when a response has been posted. It is difficult, if not impossible, to set up an account to start a new petition on the site. I was unsuccessful in four attempts to set up an account. This creates a high barrier to engagement.

Regulation Room is an experiment attempting to take a process that has been conducted in person and on paper for a long time and bring it online to reach out to people to get them more engaged.

Because of the “in person” component, Participatory Budgeting reaches people in the communities where they live. Many localities that employ a participatory budgeting process have websites that explain the process and they post information online about budget proposals that will be put to a vote in an attempt to get citizens more involved in the events.

Information

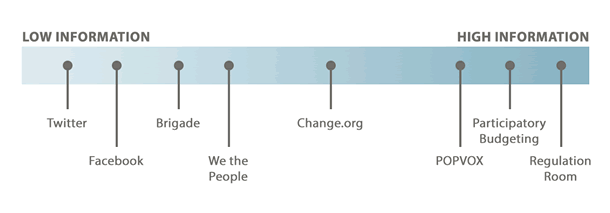

How well the information available fosters well-informed engagement.

To become engaged, supporters need to be well informed (Figure 4) about the cause they are asked to support. To be well informed, people need complete information and it needs to be written and presented in a way that is easy for people to understand.

Many of the platforms rely on user-generated information, which usually is not validated.

Brigade displays short position statements and asks users to provide their opinion about them. The only other information available on the issue are short reasons for why other users chose the opinion they did. Users can up-vote reasons to lend some level of validity to one reason over another, but it’s solely crowd sourced.

We the People relies solely on the contents of the petition, and there is no way to add additional comments and no links to any outside content.

Change.org initially relies on the contents of the petition, but there are updates, comments from other users, and related news articles available so that potential supporters can learn more about an issue before deciding whether to sign a petition. Links that are posted to Twitter and Facebook can come from any source, but the content of the information is only as good as the source and there is often no way to determine how good the source is.

Regulation Room, POPVOX, and Participatory Budgeting provide robust information. Regulation Room provides a lot of information about the rules that it supports and updates that information as the rule makes its way through the process, ensuringthat commenters are kept well informed. Commenters are also encouraged to respond to other users’ comments and build consensus, ensuring that everyone is well informed. POPVOX compiles everything they know about pending legislation, including who in the Congress supports the bill, with several easy to understand visuals about the sentiment of the issue. They make it very easy to understand an issue and drill down into the details before deciding whether to support it. Participatory Budgeting also provides a lot of information to community members. Community members are involved in early brainstorming and volunteers later flesh out the ideas into detailed proposals that are then evaluated by local government officials for feasibility and cost. Only after all this information is compiled are the ideas put to a vote.

Productive Actions

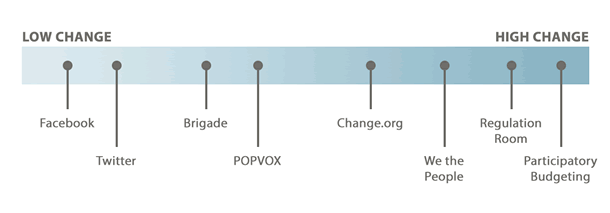

How well engagement using the platform results in actual change.

Once a supporter has decided to support an issue, the support should lead to productive actions (Figure 5). Platforms looking for feedback on issues that are already pending have a higher likelihood of affecting productive change than those that are trying to create a new issue.

At the low end of the scale, Facebook and Twitter are just flinging likes and retweets into the ether. A few viral causes may end up with media coverage, but there is no guarantee that anyone will hear about the issue or do anything about it. There are a few examples of cases where this type of engagement had an impact, like the Ice Bucket Challenge and the #BringBackOurGirls campaign, but they are few and far between.

Brigade and POPVOX attempt to verify that users are constituents of a legislator or a political candidate and attempt to use the opinions expressed on the platforms to influence those politicians. It remains to be seen whether this type of influence will actually influence politicians more than traditional offline letters. These two sites don’t currently have large enough user bases to have much impact.

Change.org does have some clout if a petition gets a large number of signatures, and because it is such a well-known site it often attracts media attention.

We the People has the power to get a response because The White House has committed to responding to any petition with more than 100,000 signatures. However, the action usually stops when a response is posted and frequently doesn’t end up producing any change. The only case that has resulted in change so far is the unlocking of cell phones.

Regulation Room provides a lot of opportunity for actual change because regulators are required to consider every comment and it facilitates a discussion between regulators and supporters that can lead to real change. Participatory Budgeting also provides for a lot of real action because it involves citizens in every step of the process and municipalities that have committed to this process have already set aside the necessary funds.

Feedback Loops

How well supporters know whether their engagement resulted in change.

In order to know if real change has happened, there needs to be feedback (Figure 6) from people who make change.

Facebook and Twitter posts provide little to no means for responding. If there’s an official page for an issue, the target can issue a response, but it may not be linked to the original post. For example, most people probably found out about the results of the Ice Bucket Challenge through the media, not through a response to a post.

Brigade only provides feedback in the form of which of your friends agree with you. It remains to be seen how they incorporate feedback from political candidates to supporters. POPVOX is similar in that the only feedback provided is how many users support an issue and whether or not your legislator supports it. There’s no immediate feedback about whether a legislator has changed their position in response to a petition sent through the site.

Other platforms provide feedback throughout the process. Change.org provides frequent updates and lets users know when a petition is successful. The White House responds to We the People petitions that meet the threshold and if any result in new laws. Federal agencies use Regulation Room to provide feedback on comments and detailed information about the regulation once it is finalized. Participatory Budgeting provides feedback from local officials about the feasibility and cost of each idea, and the voting process at the end makes it very clear which ideas have been successful.

Overall Assessment of Engagement

To arrive at the overall engagement ranking for each platform, the average ranking for the individual elements were calculated and the platforms are ordered by their averages.

Rankings for Engagement (shown highest to lowest for overall engagement)

| Reach | Channels | Information | Productive Actions | Feedback Loops | Overall | |

| Participatory Budgeting | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Regulation Room | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Change.org | 2 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Brigade | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| We the People | 8 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| POPVOX | 7 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| 5 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

Engagement is only going to evolve beyond “slacktivism” if the platform produces real change and supporters know that it is successful. In order to affect real change, platforms need to achieve the Productive Actions and Feedback Loops stages of the engagement funnel. However, they won’t get there if they don’t reach enough people and provide enough information to their users. Overall, the platforms that have a more tailored audience and are looking for feedback on causes that are already pending have a higher likelihood of fostering engagement where citizens can affect real change. The platforms that are trying to facilitate “pull engagement” to generate support for a new issue should learn from the successful efforts for existing issues already in the feedback stage.

[bluebox]

References

Code for America’s Principles for Civic Engagement

“Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital” by Robert D Putnam, published in Journal of Democracy 6:1, Jan 1995, 65-78.

Statistics cited in the carousel came from:

- https://www.change.org/impact

- http://www.participatorybudgeting.org/

- http://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahmckinney/2014/02/01/the-future-of-political-engagement-is-here-and-its-called-popvox/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/share/we-people-numbers

[/bluebox]