It is an exciting time to work in user experience because user experience jobs are now considered “hot.” When I started in the field, few companies even had such a job role. Back then only a few companies had staff doing work that would be classified as “UX” work today. Most of those companies built operating systems or consumer desktop applications software like Apple, Microsoft, or Intuit. If you asked around the technology industry when I started, most folks outside the UX profession didn’t even know the field existed.

Contrast that to the situation today. The word “user experience” is commonplace. Everyone from rank and file marketing and engineering staff to CEOs now use the term regularly. Even the venture capital (VC) community, the real power brokers in tech, are focusing on user experience. Take for example Roger Lee, a general partner at Battery Ventures, one of the largest VC firms with $4 billion in assets, who recently blogged on this topic:

“Who’s the hottest hire in Silicon Valley today? No, it’s not the data scientist, mobile app engineer, or digital marketer; it’s a user experience designer.”

Roger goes on to note that in May 2014, recruiting website Glassdoor showed more than over two thousand companies trying to hire UX designers, more than twice the number of companies trying to hire for that other hot skill, “big data engineers.” Lee is not alone in recognizing this trend. Jeff Jordan, a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, the firm founded by former Netscape alumni and backers of design-savvy firms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Uber, concurs:

“The market for engineers is always white-hot. But for designers, it’s hotter.”

Other major VC firms recognize the importance of user experience and its impact on the businesses they invest in. Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, one of the oldest and most influential of the VC firms who essential funded the early internet giants (including AOL, Netscape, and Amazon), launched a design fellows program in 2013 to help startups find talent. When the program was announced, Mike Abbot, general partner at KPCB, was quoted in Fast Company as saying:

“There’s a real opportunity to help design become the core area of focus…You go back 20 years ago—who designs products? It’s basically engineers,” Abbott says. “With tools today, a designer can get pretty far into building a prototype. Can designers start companies? I think the answer is yes.”

Mike might be right that designers can start successful companies. The growing list of designers-turned-successful-startup-founders/executives includes everyone from Rashmi Sinha, co-founder of Slideshare (former BayCHI chair and founding member of the Information Architecture Society), Biz Stone, co-founder of Twitter, to Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, the RISD grads who co-founded Airbnb, which is currently estimated to be worth $20 billion (US).

So at least in the Silicon Valley startup and VC community, user experience has come a long way; from obscurity to top-of-mind. What about outside of that community?

Business Impact: Understood

Many of the larger established tech companies are increasingly focusing on design. IBM, the grandfather of all tech companies, began reemphasizing design under CEO Ginni Rometty in 2013. In her second year as CEO, Rometty’s IBM began hiring hundreds of designers, about a 300 percent increase in overall UX staffing according to Todd Wilkens of IBM. Todd also states, “IBM Design is now responsible for the product management practice for IBM as a whole.” IBM announced last year that it would spend more than $100 million to expand its design and related consulting business, including hiring 1,000 new staff.

This is a much different IBM than the company where I began my career many years ago. Back then, many IBM UX staffers left the company to advance their careers during the dot-com boom, moving to companies like Apple, PayPal, and Netscape that valued their skills more than IBM.

Outside of traditional technology companies, firms such as Capital One, Marriott, GE, and Mercedes Benz have all made major investments in user experience in recent years. Why is this? The generation of executives who experienced the impact of design firsthand are increasingly recognizing design competency as a positive impact on business outcomes in a variety of industries.

Today’s generation of managers and executives are increasingly design savvy, almost as much as today’s venture capitalists and startup entrepreneurs. While there is some debate within the design community about the benefits of cost justification and return on investment analyses, based on the investments being made by today’s business leaders it seems they have determined there is a strong business case for investing in design.

“Years ago, we would have never thought that P&G’s design function would include interaction designers,” says P.J. Mason, principal design manager, Oral Care Innovation and Oral-B Industrial Design. “But I can see much more opportunity to include this discipline in our future work.”

Press Coverage

A big part of this change is a growing awareness of design outside of our field, partially due to the design profession’s efforts to educate others. Only 10 years ago a business magazine called to interview me about these strange positions we were hiring for that required having a deep sense of empathy and an ability to collaborate with others to design innovative solutions. That same magazine now has a regular design feature.

It’s my belief that coverage in popular media, including books, articles, and blog posts highlighting what designers really do and how that adds value, has significantly helped the profession grow. Take the following examples:

Walter Isaacson’s bestselling biography of Steve Jobs in 2011 raised awareness of the key role design has played in making Apple a success and a company that has risen to become the world’s largest publicly traded corporation. His book promoted Apple’s emphasis on design to a massive audience. As a business leader focused on financial outcomes, it’s hard to argue against the highly visible example of a company worth nearly $700 billion dollars. It’s hard to underestimate how much the story of Steve’s comeback at Apple has done for our profession.

Business magazines have also played a big role. Fast Company, for example, reaches about nearly three quarters of a million readers in print. The magazine regularly features stories on design, placing designers such as David Butler of Coke on the cover. Forbes, an even more influential business magazine with close to a million readers, has also helped raise awareness of the field in similar ways. The same can be said of Wired, the magazine popular among engineers and technology enthusiasts. You can’t underestimate the value of having your executive team pass by magazine racks at the airport where periodical covers are trumpeting the value of design.

Probably the most influential of all is the coverage of design in the highly credible Harvard Business Review. HBR, as it is known, has a readership largely composed of C-level executives and those who aim to runn companies. It has the reputation among the MBA and executive crowd as THE trusted source of management wisdom. Over the past seven years, HBR has also highlighted design’s importance to its highly influential audience.

In 2008, Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, published an article on Design Thinking linking design to corporate innovation. Tim’s article connected the dots for many business leaders who previously thought of design as limited to the corporate identity or industrial design departments. Tim’s example of redesigning healthcare delivery by an interdisciplinary team collaborating closely with end-users challenged existing concepts of design held by many of HBR’s readers.

About the same time that Steve Jobs’ passing raised awareness of his success at Apple, HBR wrote about another design-oriented success story: Intuit. In this article HBR educated its readers that it was possible to reach business success without hiring a black, turtleneck-wearing design genius for a CEO, thus giving hope to those executives who knew they weren’t Steve Jobs. The article described in detail how even a company like Intuit (already considered fairly good at user experience by most standards) can benefit from a dedicated leadership effort to ensure that the culture of design thrives and drives the business in a positive direction.

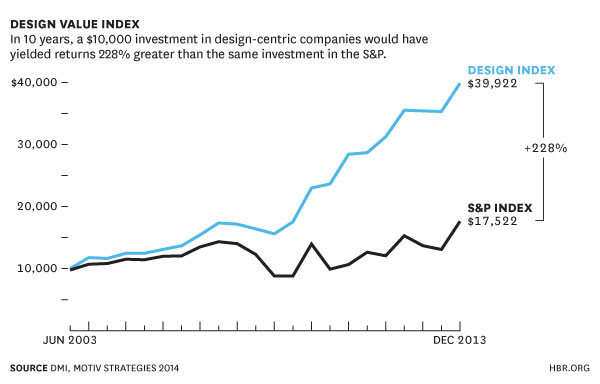

Finally, and sadly unknown to many of those in the UX profession, is the more recent HBR article highlighting the efforts of the UK Design Council and the Design Management Institute to show that design leadership is linked to shareholder value. Shareholder value—what CEOs ultimately get rewarded for—is the carrot every CEO has his or her eye on. In this 2014 article, the authors do an effective job of making the case that investing in design, including having designers in influential leadership roles, has a positive influence on company performance. They do this by charting the stock prices of companies that invest in design against the overall market. They call this the Design Value Index.

Measurable Financial Impact

The Design Value Index is the culmination of a 10-year effort by UX professionals working together and collaborating across companies and international boundaries, with input from both academics and industry.

It is increasingly accepted by those in the executive roles that good design is good business.. An examination of how we got here shows it’s not sufficient to just provide anecdotal evidence that even those in our own community debate. Just like any good design research, you have to have compelling case studies backed by hard, quantitative data that directly relates to business objectives. Examples of hard data include conversions rates in online marketing and ecommerce as well as impacts on Net Promoter Scores. Of course creating shareholder value is the ultimate goal for most companies, so the Design Value Index brings it to a new level.

Data like this is important not just to convince executives to initially invest in design, but to guide those investments over time.

Maintaining Relevance

So now that it appears that we’ve got the attention of business leaders, how do we keep it? How do we avoid becoming a passing business fad?

Now that we’ve been granted a place at the table we need to work hard and differently to maintain it. We need to operate at a more strategic level to really add the value that justifies being more than just a member of a project team executing against someone else’s plan for which we have no input.

I believe that many in our profession know this, and this is what’s driving the current interest in UX strategy. In the past two years, several conferences have sprung up dedicated to the topic of UX strategy, and almost every UX conference has talks on this topic. It’s also increasingly common to see the words UX strategy in job titles and job descriptions. As of July 2015, the job site Indeed.com showed 562 results for the term “UX strategist.”

When Liam Friedland and I first began speaking on UX strategy at CHI and UPA back in 2003 it was a relatively new topic; reviewers of our submissions back in those days didn’t know if there would be any interest in the topic. Clearly interest exists, and despite current trends there remains some debate in the UX community on whether the concept of a UX strategy is even valid. Jeff Gothelf, author of the popular Lean UX book argues:

“The reality is that there is no such thing as UX strategy. There is only product strategy.”

I think that Jeff’s partially correct. He’s right in that every product initiative should consider UX. I think he’s over simplifying however. Every product strategy should consider sales and marketing factors. That doesn’t mean you don’t need a sales and marketing-specific strategy at both a product level and a corporate level, formulated by people who really understand those areas. There are really two different questions that a well-formulated UX strategy must address:

- How do we design the best user experience for a specific product?

- What is the best way to create and manage UX at a company?

Note the interrelationship between these two questions. A UX strategy for a given project/product is obviously not just smaller in scope, but it is formed within the larger context of the company’s UX strategy and corporate strategy.

Part of the reason the Lean UX and Lean Startup models exist is that startups by nature are different than companies selling existing products to existing markets. Lean UX assumes a UX strategy appropriate for Lean startups.

In a larger company you may in fact decide not to try to create a great experience for a specific product or feature when working on many things, simply because of inadequate UX resources. The business strategy may dictate that a particular product is not a UX priority. It might also make sense tactically to take different UX approaches on different projects due to the nature of the projects. These are all valid UX strategies.

Part of any strategy is deciding what not to do. Take for example the now famous approach to product strategy that Steve Jobs took upon his return to Apple. Jobs killed a bunch of projects, including the early tablet computer project known as the Newton. Later, when Apple returned to working on tablets they took a very different approach to the design of the iPad (arguably an example of a UX strategy).

In terms of running UX, after Jobs returned from Next, Apple as a company didn’t continue to fund long-term research in the same way. This is also an example of UX strategy. Apple abandoned the approach of having a corporate research laboratory working on future UX-related technologies, such as handwriting recognition, which was core to their original Newton tablet design strategy—an approach tightly linked historically to UX work modeled after Xerox’s approach at PARC.

Most startups today focus on the short-term problem of finding a business model to survive and creating a minimal viable product to test product-market fit. They typically work on a single product or service working in a serial fashion in small-dedicated teams. In contrast, larger companies have to determine how to optimize processes and efficiently run things at scale, including making decisions outside the scope of a single product context. Different situations require different UX strategies.

Take Google for example. For years Google ran projects largely without much design coordination across teams, basically running things like a bunch of startups under the same roof. This approach was no doubt influenced by their rapid rate of growth and the relative importance of UX in their markets. Things changed when CEO Eric Schmidt passed the reins to founder Larry Page in 2011.

Coordinating cross-product design work recently became more of an emphasis at Google. Once Larry Page got more involved, collaboration across teams increased. Design work was consolidated and UI standards were rolled out.

Evelyn Kim, design lead at Google, said, “We feel the effects on our jobs. There’s this trickle-down effect where I’m involved with more strategy, whereas I could never do that eight years ago.”

Now that Google has altered its approach under Page, we have Material Design Guidelines that are available publically. These guidelines are key to enabling Google’s mobile strategy, which depends largely on external partners and developers. After taking over, Page shut down close to 70 projects in order to better focus the company. Google Labs was closed. Google Ventures investment increased 4x, and includes having Google Ventures designers help portfolio companies with design. Things are much more top-down driven. Sound familiar?

“The time when engineers can work on arbitrary user-facing ideas in nearly full isolation from the top, and still hope to be hugely successful, is now largely gone.” (Originally from an anonymous post on Quora)

While Google still doesn’t have a chief design officer like Apple’s Jonathan Ive overseeing all the design work centrally, they have definitely have moved in that direction.

As of July 2015, Google stock is up. Larry Page is approximately $7 billion dollars richer thanks to Google stock’s 24% increase and a record high. This is an impressive feat for a company now worth just under half a trillion dollars. Can this be attributed entirely to design? No. But Larry’s visible push for change in how the company designs products was clearly part of his strategy.

Conclusions

The current state of design awareness didn’t come overnight. It’s a result of the maturity of the industries adopting design as a best practice and knowledge of the impact of design spreading via word of mouth and through popular media.

The companies listed in the Design Management Institute’s Design Value Index are mostly led by those that have either worked in the design profession personally, or had firsthand experience with it during their careers. If UX professionals hope to continue to remain relevant, they need to rise up the corporate ranks as leaders or engage with those who do.

There are many executives who have design awareness yet lack a deep understanding of the process details required to engage in design strategy discussions. These individuals often rose to their positions during the era of the “launch and pray” paradigm. It’s important that they be educated about how design is run at other companies and helped to understand the details of internal projects. This includes making an effort to speak the language of business, like translating projects into financial outcomes, as well as providing other objective measures of design impact that non-designers can understand.

As the profession grows, we need to ensure we embrace the specialization that makes us more effective in specific domains (for example, interaction versus industrial design) while maintaining the value of the inclusive and holistic perspective of design that allows us to connect the dots that are the sparks of creativity. Not just welcoming new ideas, or embracing them, but actually seeking them out with the understanding that the best of these ideas will make us better at design.

In the same manner, we must increasingly connect and collaborate with those from other disciplines and backgrounds to be effective at scale. This includes reaching out to business leaders at all levels and teaching them design thinking so they feel part of the process and understand design more deeply. This approach will help us expand our sphere of influence and allow us to have a greater impact upon the world. This is the only way we can remain relevant as leaders of design in comparison to those who come from non-design backgrounds.

[greybox]

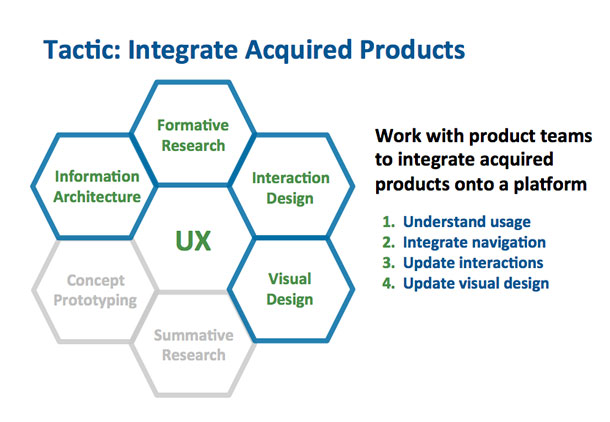

Full text from Figure 2. Tactical Resource Allocation

Tactic: Integrate Acquired Products

Work with product team to integrate acquired products onto a platform

- Understand usage

- Integrate navigation

- Update interactions

- Update visual design

Methods to use:

- Information architecture

- Formative research

- Interaction design

- Visual design

Methods not relevant

- Concept prototyping

- Summative research

[/greybox]