The internet has evolved into a social gathering place in which users no longer just consume online content but actively generate, curate, disseminate, and reshape it across various platforms. People are benefitting from advances in online social technologies through increased access to people, goods, and information in social, professional, commercial, and even civil realms. However, some people also experience negative social consequences, such as information overload, misinformation, increased pressure to be responsive, and cyberbullying. Worries about encountering these consequences are characterized as social privacy concerns; this includes psychological threats, pressure to interact with others, unwelcome influences on character development/opinion formation, or otherwise feeling unsafe in an online environment.

Research shows that many users decrease or stop their use of online platforms because of social privacy concerns. This is leading to a new digital divide between those who use and benefit from an increasing variety of features and online technologies and those who limit their engagement with these platforms because of social privacy barriers. Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the world wide web, emphasized the importance of addressing this gap as the web recently celebrated its 30th anniversary:

“Of course with every new feature, every new website, the divide between those who are online and those who are not increases, making it all the more imperative to make the web available for everyone.”

We argue that, as UX designers, we have the opportunity and the ethical responsibility to design for overcoming social privacy barriers. In this article, we draw on our research and experience to illustrate how social privacy concerns affect users or even push them away from using online platforms. We conclude by suggesting ways forward to more responsible UX design.

Privacy as Balancing Social Connectedness against Isolation

While the word “privacy” is often used to describe the desire to withhold information, to be less accessible, or to be free from outside influence, classical definitions emphasize that privacy is more about achieving the right balance between being more or less accessible, sharing more or less information, and achieving more or less social connection. Drawing from social psychologist Irwin Altman, privacy can be defined as “an interpersonal boundary process by which a person or group regulates interaction with others,” by altering the degree of openness of the self to others.

In this conception of privacy, being too isolated is as much a privacy problem as being socially crowded. As a result, we find that people either endure the various social, financial, and even physical consequences that come with being socially connected, or they are so concerned about these problems that they minimize or give up social connection through online platforms. Here are a few examples of how this manifests in our work.

Social Media Users and Privacy

The desire to connect socially is especially important when looking at technologies such as social media. Research shows that people benefit the most from being on a social media platform when it gives users the level of privacy they want; however, using the platform’s privacy functionality involves a complex and highly personal act of navigating numerous privacy boundaries. Privacy settings can be difficult to find or understand. People can also be confused by internal jargon that social media companies use, which makes it difficult to navigate privacy settings.

Even when these settings are used, they do not always support evolving privacy desires and needs. Over time and in different contexts, users’ privacy expectations change, and industry must meet the challenge of satisfying these dynamic and nuanced preferences. Users often make trade-offs among context collapse and sharing with a too-broad audience, not disclosing at all, and spending cognitive and temporal effort to carefully manage communications.

Also, certain groups of users may require special consideration. For example, older users are especially susceptible to making mistakes, given their lower technical literacy; they require greater education on issues such as the implications of particular features and the public posting of material.

Despite the availability of privacy features, studies show that some users do not use them. In fact, our ongoing research suggests that certain individuals may actually resist using certain privacy features because of the negative social meaning that may be conveyed to others (e.g., when a user unfriends or untags someone). This perceived pressure sometimes influences users to expose themselves to social privacy harms they otherwise would have protected themselves against.

Teens, Privacy, and Online Safety

Networked technology is an ever-present force in the lives of nearly all teens in the United States; according to Pew Research, 95% have access to smartphones, 89% of teens go online multiple times a day with 45% reporting near-constant connectivity, 71% engage in more than one social media platform, and 57% have met new friends online.

Yet, the internet is a double-edged sword; it facilitates opportunities for teens but also amplifies risks. Teens can benefit from online interactions that allow them to explore their self-identities, seek social support, and search for new information. Meanwhile, rates of depressive symptoms, self-harm, and suicide of teens in the U.S. have dramatically increased with the rise in adolescent digital media use.

Even teens themselves are ambivalent about the effect the internet and social media has had on their lives: 31% think it has a mostly positive effect by helping them connect with family and friends, 45% are neutral, and nearly a quarter of teens (24%) feel that social media has had mostly a negative impact on their lives due to increased bullying, social comparisons, interpersonal conflict, a lack of personal closeness, and its propensity to contribute to mental health issues. The Crimes Against Children Research Center reports that 1 in 4 youth in the U.S. have experienced unwanted exposure to internet pornography, 1 in 9 have been victims of online harassment, and 1 in 11 report receiving unwanted sexual solicitations online.

According to Wisniewski et al.’s body of research with adolescents (ages 13–17), the current paradigm for keeping teens safe online focuses heavily on “abstinence-only” approaches that increase parental control through features that may monitor and restrict a teen’s online activities, often to support existing legislation. This approach relies on heavily direct parental oversight and may cause privacy tensions between parents and teens that do not reflect the diverse needs of different families. Further, it ignores the fact that teens who are the most vulnerable to online risks often do not have actively engaged parents to protect them online.

These facts show a need for safety mechanisms for online platforms that are developmentally appropriate to empower adolescents in a way that they become risk resilient. This is particularly true for the teens who are most vulnerable (e.g., foster youth) to the most serious online risks (e.g., sexual predation and cyberbullying) because they are often those who lack engaged and supportive parental supervision both on and offline.

As danah boyd (styled in lowercase) aptly put it in her book, It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens:

“As a society, we often spend so much time worrying about young people that we fail to account for how our paternalism and protectionism hinders teens’ ability to become informed, thoughtful, and engaged adults.”

Social Media Non-Users and Social Disenfranchisement

With 76% of online adults using Facebook (the most popular social media platform) and three-quarters of these logging on at least daily, social media usage has become the norm, according to the Pew Research Center. Benefits include increased social capital, psychological well-being, socioemotional support, civic engagement, and improvements in the workplace. However, many people are unable to use social media and cannot enjoy these benefits.

In fact, 31% of U.S. adults do not use social media at all. Various reasons have been highlighted such as technical literacy, socioeconomic factors limiting access, and more mundane objections to irrelevant content. However, in Page et al.’s body of work on non-use and limited use, they identify a previously unrecognized class of non-users who encounter social consequences whether they are on or off social media, resulting in a lose-lose situation of social disenfranchisement (“Social Media’s Have-Nots: An Era of Social Disenfranchisement” provides an introduction). They uncover social barriers that prevent these individuals from using social media (e.g., harassment, being overwhelmed by social decision-making, feeling inadequate about their social media engagement, social anxiety).

Moreover, these non-users continue to experience negative consequences even off social media (e.g., they are still harassed, left out of social engagements, lose control of their online identity that is now being shaped by others). They find that they are in a lose-lose situation of social disenfranchisement as society integrates social media in an ever-increasing number of life spheres. Our latest research investigates how this type of social disenfranchisement is disproportionately affecting some of the most vulnerable individuals, such as those with disabilities and the elderly.

Towards Responsible Privacy Design

As UX professionals, we are positioned to shape the user experience of these social technologies. Moreover, given that the features and user experience can shape the non-user experience as well, we have an ethical responsibility to design for both. Practically, this means that we should do what we can to alleviate the negative social consequences that result when our features are put into play and even repurposed by users. We advocate for consideration of various user types, such as signed-out users, teens, and those who are vulnerable.

These applied ethics for designers and researchers will require assessments of the trade-offs and consideration for what should be done in specific situations and interactions. They will also require that we are open to feedback, that we seek to deepen our understanding, and that we acknowledge that designs will likely evolve and need to change as we discover problems or as users employ our technologies in ways we did not anticipate. However, we believe that by extending concern for users in this space, we will be creating a better internet for everyone.

Here are some ways that we can work towards more responsible privacy design.

Identify Privacy Problems and Concerns and Make them a Priority

This article is a step towards identifying problems and tensions that designers should consider. It is based on research and observing users and non-users. UX professionals should be informed about the latest findings to anticipate problems that they should account for in their design. However, every platform is unique, and users can surprise us with the ways they use new features.

Studying non-use is also critical; the challenges faced by people who do not use a platform may be very different from the challenges of people who do. For example, those who experience harassment or social anxiety offline may avoid online social media because of their increased susceptibility, whereas users of that social media may not have ever experienced those concerns and risks. Understanding the needs of non-users can lead designers to tackle a very different set of problems. Thus, studying people to understand the more nuanced social forces at play is key to identifying problems and concerns for your platform.

Acknowledge Individual Differences

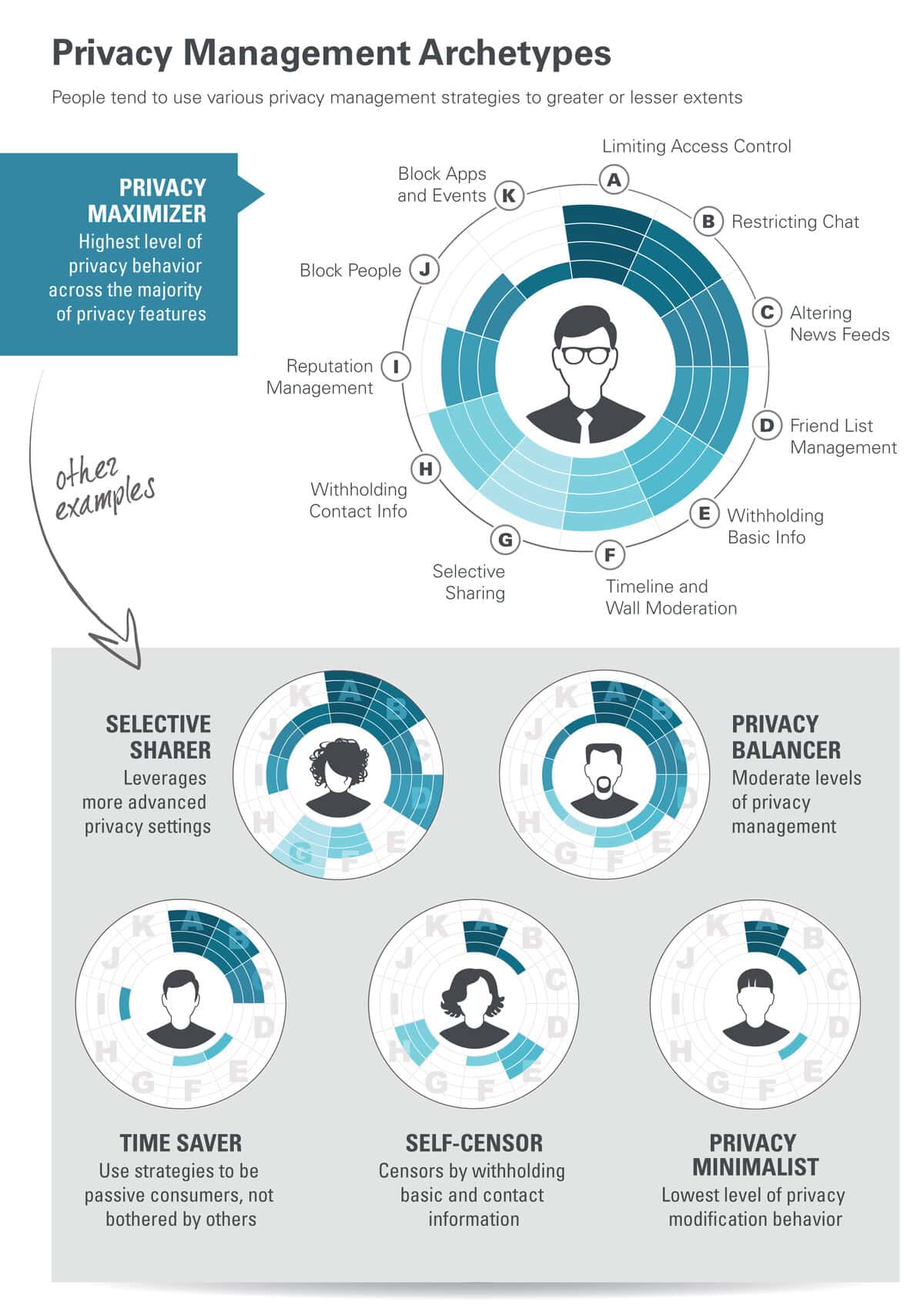

One of the most well-established findings in privacy research is that people differ in terms of their privacy preferences and behaviors. For instance, people have varying strategies that shape their privacy management tactics. Different profiles have been identified (see Figure 1), such as people who are motivated by time-savings and who want to minimize the information they need to wade through (e.g., in their feed). Other research uncovers an FYI communication style preference where users see much more value in technology-mediated communication and exhibit much lower privacy concerns.

To address these, UX professionals should take an inclusive approach to privacy design, with a special focus on underrepresented and vulnerable populations. For example, with the proliferation of smart home technologies (such as smart thermostats, doors, cameras, and speakers), everyday devices are now connected to the internet. These make it easy to check on your home while you are away and to enjoy conveniences such as automatic climate control and cost savings. However, researchers and the media have recently raised awareness around how these digital tools can perpetuate domestic abuse in unhealthy relationships. Design solutions for social privacy may require a level of sophistication that goes beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to something that can be tailored to the individual user and circumstance.

Figure 1. Privacy Management Archetypes. (Credit: Elizabeth A. Bradley)

Bridge Academia and Industry

The corporate world is often criticized for being motivated by profit and moving too fast to think deeply about end-user privacy. However, with the recent media on privacy breaches at numerous large companies, making privacy a secondary consideration is no longer an option. We see an opportunity for industry design to be guided by evidence-based research. By partnering with academic researchers who specialize in thinking deeply and critically about how to solve end-user privacy concerns, industrial partners can show their commitment to independent scholarly research and to addressing privacy challenges that have no easy solution.

Conversely, academics are often criticized for lacking relevance and trying to solve problems that do not matter. As such, academics could benefit from working with people in the industry to tackle real-world problems using relevant data and to conduct research that has a practical value to society.

By working together, we can help one another and ultimately help society by designing and supporting end-user privacy. Collaborations could include agenda-setting discussions, research studies, and user research data exchange. Our positive experiences reaching across this divide and participating in one another’s communities reinforces how this will assist designers and researchers in creating better experiences for everyone.

Go Beyond UX Design

While UX design is an important and immediate way to address privacy problems, there are regulatory, societal, and other forces at play that also need to be considered. As a community, we need to establish a set of shared values and work towards realizing them in these other areas, whether it be through shaping policy or appealing to market forces. This conversation is beyond the scope of this article, but we encourage UX professionals in industry as well as academia to be aware and proactive when it comes to giving input on proposed policies and explaining the privacy implications to those outside the field. We believe that UX professionals should push to consider the broader picture and advocate for the right to social privacy for everyone in our society.

To work towards these goals, please join our community of practitioners, academics, policy-makers, and other privacy thought leaders at Modern Privacy, where we post upcoming events, links to resources (such as an upcoming open-access book on the latest privacy topics), and offer a design library of privacy principles for the community to freely use and contribute to.

Appendix: Privacy Management Archetypes (Figure 1 Transcript)

People tend to use various privacy management strategies to greater or lesser extents

Privacy Maximizer

Highest level of privacy behavior across the majority of privacy features

- Limiting access control (high)

- Restricting chat (high)

- Altering news feeds (medium)

- Friend list management (high)

- Withholding basic info (none)

- Timeline and wall modification (medium)

- Selective sharing (medium)

- Withholding Contact Info

- Reputation management (low)

- Block people (low)

- Block apps and events (very low)

Other Examples

- Selective Sharer: Leverages more advanced privacy settings

- Privacy Balancer: Moderate levels of privacy management

- Time Saver: Use strategies to be passive consumers, not bothered by others

- Self-Censor: Censors by withholding basic and contact information

- Privacy Minimalist: Lowest level of privacy modification behavior