The emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has taken its toll on everyone and has greatly intensified the need for accessible mental healthcare. According to the American Psychological Association’s Report Stress in America™ 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis, “nearly 8 in 10 [American] adults (78%) say that the coronavirus is a significant source of stress in their life.” Additionally, there has been an added financial consequence from the pandemic, particularly felt by households with income of $50,000 or less. This report found these respondents are at a higher risk of being laid off, and 73% of the respondents within this income bracket claimed that money, or the lack of it, was an increased source of stress during the pandemic.

A critical and rapid expansion of telehealth has occurred due to the pandemic. Many insurance companies and the US Medicare system have lifted prior restrictions for billing remote sessions in order to provide mental healthcare and prevent the spread of COVID-19. However, our research shows that most individuals are not taking advantage of the available digital mental health tools, even when they could really benefit from them.

The UW ALACRITY Center was given a grant by the US National Institute for Mental Health to study the acceptability, usability, and effectiveness of mental health apps for suicide prevention among essential workers and people experiencing unemployment during COVID-19, because these two populations have experienced significant hardship during this crisis. Our research team included psychologists, research coordinators, data scientists, and myself, a UX researcher. Our survey included almost 2,000 participants.

We are providing updated results from this study and the second phase of the study when completed. This PDF document will be updated with our findings for the different phases of our ongoing study. By sharing our findings, we hope that developers of future apps and digital tools will be able to build on this information to increase their apps’ usability, popularity, and ease of engagement.

Why Focus on Essential Workers and People Experiencing Unemployment?

While research has been conducted on the negative impact of the pandemic on the general population and frontline healthcare workers, there has been limited research about the specific mental health needs of essential workers and those who are experiencing unemployment due to COVID-19.

Access to mental healthcare in general can be difficult. The US Department of Health and Human Services reported to Congress that 55% of US counties don’t have a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker. During the pandemic, getting help has been particularly challenging because the usual access to mental healthcare is limited by social distancing. Essential workers often have heightened concerns about the risk of being exposed to or spreading the coronavirus due to having a lack of personal protective equipment and other factors. These workers generally have very little free time for self-care and may struggle to balance between increased work demands and caring for their family. Individuals that are recently unemployed or furloughed due to COVID-19 have stressors that may include financial pressures, loss of health insurance, inability to afford treatment, uncertainty about future work, balancing caring for their family while searching for employment, and feeling guilt about not being able to contribute.

With all this in mind, we were curious to see if and when people from these two groups— essential workers and those experiencing unemployment due to COVID-19—have been turning to online interventions, such as mental health apps and other online resources. We also wanted to explore how well these tools were meeting their needs if they were using them.

Digital Mental Health Tools

The landscape of digital mental health tools (DMHTs) includes technology-based care such as telehealth or message-based care or apps, which may be auto-guided or user-guided. Many public health systems, such as the US Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare system, and digital mental health companies have responded to COVID-19 by increasing access to existing technology-based care (i.e., telemedicine) or modifying/releasing apps designed to address this growing need. Some of these apps are specifically geared toward coping with pandemic-related stresses.

There are several types of DMHT supports. Virtual telemedicine appointments with clinicians, for example, can address the shortage of providers in particular geographical areas. Additionally, telemedicine appointments eliminate the need for travel, which can be especially helpful considering the COVID-related struggle for childcare. However, privacy issues arise as people struggle to find space alone in which to hold personal conversations, and a lack of reliable access to the internet continues to be a problem for many. As another example, asynchronous messaging through an app can also provide an alternative to face-to-face sessions, with patients texting or exchanging voice or video messages with their therapist or coach at their convenience. Finally, non-clinician based digital mental health tools include chatbots and apps that deliver content and exercises frequently grounded in evidence-based practices, such as cognitive behavioral therapy.

Our Methods

We surveyed almost 2,000 participants between the ages of 18 to 78 regarding which apps and online tools they have used to manage mental health issues during COVID-19. We asked them what usability challenges they had faced with these digital supports. All participants were either essential workers or experiencing unemployment due to COVID-19.

We assessed the participants’ mental health status using clinically validated measures for depression (PHQ-2), anxiety (GAD-2), emotion dysregulation (DERS-18), substance use (CAGE-AID), and risk factors for suicidal behaviors (SBQ-R). We asked people with and without mental health symptoms why they did or did not use digital supports for mental wellness. If participants reported using an app, they were asked to share more details about the app’s features, usability, user burden, and their likes and dislikes about the app. User burden considered whether the app was burdensome to use due to difficulty navigating the app, distraction in the context of social situations, or because it was too costly.

Mental Health Apps Have a Public Relations Problem

Statista, a leading provider of market and consumer data, reported in November 2020 that the leading mental wellness apps were installed 215,000 times in the United States. This number was up from 158,000 the year before the pandemic.

We asked the participants in our study if they used an app to help cope with stress associated with COVID-19. Only 14% of our participants reported using this type of app, with no difference shown between essential workers or those experiencing unemployment. When we asked the other 86% of our participants why they chose not to use an app to cope with COVID-19 stress, the majority (69%) answered “I didn’t think to look for an app,” followed by “I don’t think apps would help me” (35%), and “I have other ways of coping” (25%). People whose responses to the screeners that suggested they were experiencing mental health symptoms were only slightly more likely (16.1%) to use mental health apps. The findings are even more surprising given that the average age of our respondents was 32, which is the millennial age group, a group of people who are generally very comfortable with technology.

In 2017 a survey from Statista with almost 1,000 respondents found that 45% of people age 30 to 45 and 52% from 18 to 29 had used an app to track their fitness occasionally or regularly. These results coupled with the responses from our survey indicate that the mental health apps may have a public relations problem, rather than a usability issue. It’s possible that people don’t think to look to apps for this kind of help, and people who need help are not convinced that an app will provide enough value to even try using one.

A Desire for Meditation and Mindfulness Strategies to Cope with COVID-19

The two most popular apps for our study participants were Calm and Headspace, both self-guided apps designed to teach mindfulness and meditation in order to improve the quality of sleep and reduce stress and anxiety. Users of these apps appreciate the variety of programs available, and that they are well designed, easy to use, and customizable. Our participants’ comments describing what they liked included, “I liked that [Headspace] encouraged me to find healthy ways of managing my sadness and anxiety in a nonjudgmental way,” and “[Calm] forced me to focus on my breathing and to take my mind away from what was going on.” Headspace was regularly described as “easy to use” while Calm was repeatedly described as relaxing, with many people mentioning its music options. Tracking apps, such as eMoods and Sleep Cycle were mentioned as useful for becoming more mindful. Users of apps, such as Headspace, remarked they wished that tracking was something that could be incorporated into the app.

Interpersonal Therapy Options

Another category of apps used by our participants were online counseling and therapy services provided through web-based interaction, as well as phone and text communication. The most popular option was BetterHelp, followed by Talkspace, and Babylon. Users like the access to a person, the flexibility of scheduling, and the ability to communicate between sessions. Issues with connectivity/video stability were a regular complaint. There were also people who reported issues with not being matched with therapists who met their criteria (e.g., age or gender), trouble consistently connecting with the same therapists, and having been “ghosted” by their therapist, (i.e., where their repeated attempts at connecting were ignored).

AI Based Apps

AI based mental health apps such as Woebot, Wysa, and Replika were generally enjoyed by our participants. One participant summed up their experience with the Replika app describing it as “an A.I. friend who gives very genuine and realistic responses. She’s there for you 24/7 and will remember things about you to be a lifelike companion who never leaves.” One complaint repeated by multiple participants about the AI apps had to do with the app offering too much advice and not “listening” to a person: “It sometimes tries to psychoanalyze me when I really just need a way to vent some frustrations. It doesn’t always recognize when I need help, versus when I just want an ear.” Similarly, there was an interest in increased customizability and less repetitiveness: “A lot of [Woebot’s] responses were very generic. At times, they were also really repetitive. It annoyed me to the point where I didn’t think it was helpful after a short time.”

One final interesting note about this survey was that our question “Have you downloaded or used an app to help you cope with stress associated with COVID?” was interpreted in many different ways. A notable portion of respondents mentioned apps that were not specifically mental health focused, but that they found helpful. Apps such as TikTok, Zoom, or games provided welcomed distractions, entertainment, or a way to connect socially. Participants also mentioned that apps tracking local COVID-19 outbreaks gave them some small sense of control.

Cost of DMHTs Was a Concern

Across all of the app categories, the number one complaint was cost. Many of these apps offer free basic versions with ads and with the ability to download additional packs or features for a fee. Not surprisingly, with more than half of our respondents being unemployed and 60.7% of our respondents reporting an income of less than $50,000 (and 25% earning $10,000 to $31,199), affordability was a high priority. Many people took advantage of partnerships formed by insurance companies, covering the subscription to apps such as Calm and Babylon. This seems like a wise path forward to ensure better access for those who have health insurance. Additionally, this would be helpful for those who have limited access to care due to living in remote areas, people with financial stress who cannot justify spending their money on their mental health, or those who initially don’t think these apps are worth the investment. Of course, this path still doesn’t address the needs of the uninsured who already have the fewest resources.

User Burden

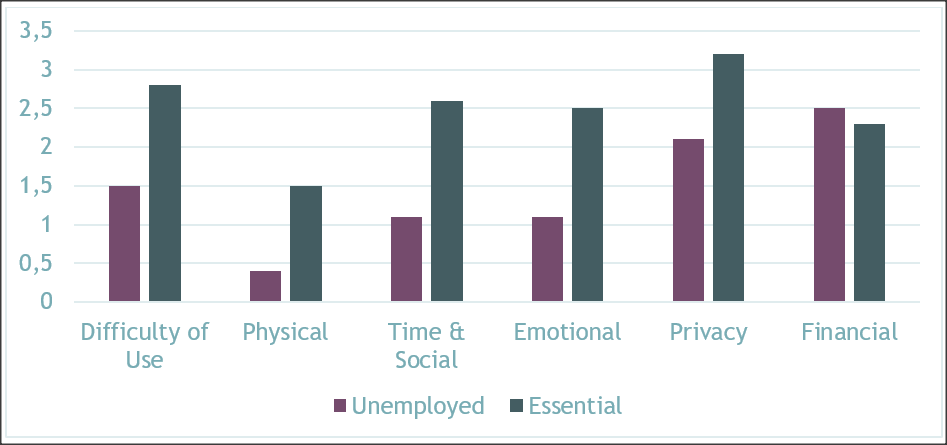

Those who were currently using a mental health app were asked to fill out the System Usability Scale (SUS) and the User Burden Scale (UBS) to rate their experience using that app (see Figure 1 for the reported burden). The most notable finding from these scales was that generally essential workers reported higher levels of burden than the people in the unemployed group, suggesting they may have increased fatigue due to elevated anxiety from work and increased work demands during the pandemic. Mental health app UX professionals should be aware that users dealing with ongoing stress, in this case essential workers, likely require greater attention to ease of use in their design.

Figure 1. Reported burden of using mental health apps. (Credit: Felicia Mata-Greve)

Figure 1. Reported burden of using mental health apps. (Credit: Felicia Mata-Greve)

When asked to look at a list of features and rate how important they felt they were for a mental health app, both groups listed the following top four features:

- Information or education

- Mindfulness/meditation tools

- Tools to focus on the positive events and influences in life

- Link to resources, counseling, or crisis support

However, the participants experiencing unemployment ranked “mindfulness/meditation tools” as number one, above information or education. Looking at just the participants who screened positive for mental health distress, the priorities were the same for both groups.

We concluded our study by asking participants to “build your own app” by choosing from a list of features (and the ability to add their own if it wasn’t listed). The results of this are in Table 1. Suggestions for additional features mainly fell into two categories:

- Productivity tools, like alarms or lists, to help with motivation/attention issues (generally, and for regularly using the app)

- Features to facilitate communication/connection with friends or other peers struggling with similar issues.

Table 1. Building Your Own App

| Build your own app features | Unemployed (N=1013) |

Essential worker (N=974) |

Total (N=1987) |

| Information or education | 636 (62.8%) | 618 (63.4%) | 1254 (63.1%) |

| Mindfulness/meditation | 687 (67.8%) | 584 (60.0%) | 1271 (64.0%) |

| Symptom tracking (trackingsleep or mood) | 605 (59.7%) | 555 (57.0%) | 1160 (58.4%) |

| Brain games to improve thinking | 525 (51.8%) | 480 (49.3%) | 1005 (50.6%) |

| Distraction tools (drawing, puzzles, music) | 630 (62.2%) | 540 (55.4%) | 1170 (58.9%) |

| Tools to focus on the positive events and influences in life | 578 (57.1%) | 553 (56.8%) | 1131 (56.9%) |

| Links to resources, counseling, or crisis support | 604 (59.6%) | 536 (55.0%) | 1140 (57.4%) |

| A chatbot to help you with daily stress | 352 (34.7%) | 293 (30.1%) | 645 (32.5%) |

| How to cope with COVID | 406 (40.1%) | 409 (42.0%) | 815 (41.0%) |

(Credit: Morgan Johnson and Michael Pullmann)

This is not the first study to find that the use of digital mental health services tends to be poor. Most people who download these tools often discontinue use in a short period of time. Besides being designed with an emphasis on usability, digital mental health services could be improved if intervention developers better understand what features users felt are the most important to have and what feedback the apps need to provide to keep users engaged. Finally, the developers need to clarify what role these apps should have in the greater context of mental wellness services. As mentioned earlier, collaboration with insurance companies can help address concerns about cost and assist with widespread promotion. Greater attention should be paid to educating the public about the utility of these apps. Educating both the public and providers as to the available options and their efficacy increases the chances that they will be used by the people who need them.

Acknowledgments

I was fortunate to be part of this research team lead by Kate Comtois, PhD, MPH and Pat Areán, PhD. The team also included Felicia Mata-Greve, PhD; Morgan Johnson, MS; Michael Pullmann, PhD; and Isabell Griffith Felipo, BA.

Emily Friedman, MID, CPE is a designer, researcher, and human factors/usability specialist who has led design efforts with a focus on healthcare delivery. As the User Research & Design Lead for the UW ALACRITY Center, she leverages user-centered design to expand the reach of mental healthcare to traditionally underserved communities.