Figure 1. A person standing in a doorway soaked from pouring rain. (Generated with Adobe® Firefly™ [Artificial intelligence system]).

Introduction

We invite you to visualize the story in the above graphic (Figure 1). You answer your house door to find your friend sopping wet from a surprise rainstorm. Would you act as if the situation were perfectly normal and ignore that they are soaking wet? Would you be annoyed at them for dripping all over the floor? Either option seems absurd, right? Why would you do that to your friend?

But that’s what we do when we invite our audiences to our websites, apps, and other experiences without thoroughly understanding and deliberately considering how trauma has impacted them (because it does). Often unintentionally, we ignore their whole lived experience, pretend trauma didn’t happen, and potentially cause them (further) harm.

Trauma is widespread. Research finds that people around the world experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, with four or more events being the norm. What’s more, when people or groups experience an event as traumatic, it changes them. It can forever alter how they think, remember, and perform daily tasks, including how they interact with technology.

Imagine a world in which technology—current and emerging like AI (and whatever comes next)—was mandated to promote well-being and proactively prevent new or further trauma (instead of reacting to it as it happens). This new world can be achieved by designers becoming trauma-informed.

Our article calls on all designers. To serve our audiences well, we must first learn more about trauma so that we can deliberately account for it in our design work and research. While some of what designers currently do as standard practice aligns well with trauma-informed approaches or is thoughtful of inequality and accessibility, their approach lacks the necessary careful and deliberate attention to trauma. As designers, we can and should leverage the undeniable power of trauma-informed approaches that social workers have applied for years to meet the global need for safe, supportive, equitable, and trustworthy technology.

In this article, we start by explaining trauma, including who experiences it, its impact, and what happens when people face new or similar incidents (re-traumatization). We then describe what we mean by trauma-informed design, offering opportunities and ways to begin applying trauma-informed approaches in different scopes of practice. We conclude by offering practical examples of how trauma-informed design work can reduce the likelihood of re-traumatization.

With all this in mind, let’s embark on a journey together to unpack trauma and trauma-informed design. In doing so, we’ll uncover the value of trauma-informed work and why it is imperative, especially in our post-COVID and war-torn world.

Understanding Trauma: What, Who, and Why

Trauma is a universal experience. Health researchers conducted one of the most extensive global trauma studies, surveying 24 countries and over 68,000 adults. They discovered that about 70% of people worldwide experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, and 30.5% experience four or more. According to findings from a large national survey, that number increases to at least 90% of adults in the United States (U.S.). We hypothesize that the global experience of trauma would also be close to 100% if research broadened its definition of trauma and asked participants about specific scenarios or events like the ones we outline below.

If you thought, “Wow, that seems high,” we invite you to reflect on your definition of trauma. What does trauma mean to you? What’s the first thing you think of? We assume that chilling and disturbing experiences like sexual abuse came to mind, or maybe alarming and shocking events like war and mass destruction.

But what if we told you that trauma is much broader than you might think?

What Is Trauma?

You are not alone if you thought trauma had to be a disturbing, shocking, or unthinkable event. From our experience of speaking with hundreds of people with trauma histories, we find that most people don’t identify as having lived experience of trauma mainly because they think trauma is an individual experience and must be something big or extremely harmful.

But trauma is so much more than that. It is also bigger than simply going through a very stressful experience. Trauma is a life-changing experience or event that profoundly impacts the mind (emotionally and physiologically) and body (physically and physiologically) of those who experience it.

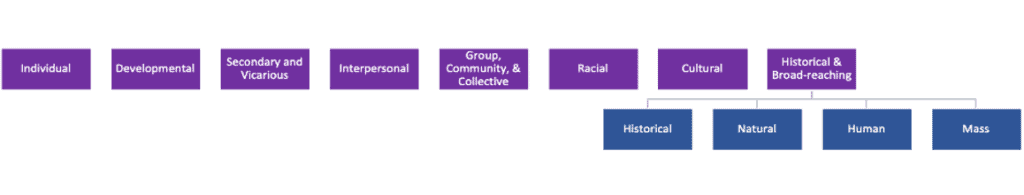

The best way to explain trauma is to describe the various types (Figure 2). For brevity, we name and supply an example for each type. The CHI 2023 article, by one of the authors and her colleagues, and its supplementary video about trauma-informed social media (PDF available) further explain these types. Also, it’s important to know that these types of traumas are not mutually exclusive, and the order in which we present them does not denote their significance or prevalence.

Figure 2. The many types of trauma.

A large body of global research has identified 11 types of trauma:

- Individual trauma (a person experiences a mugging, a medical trauma like cancer, rape, or being a military soldier fighting in a war or battle)

- Developmental trauma (child sexual abuse or elderly abuse)

- Secondary (seeing or hearing about another person being assaulted) and vicarious trauma (doctors exposed to prolonged patient suffering, like during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic)

- Interpersonal trauma (intimate partner violence or bullying)

- Group, community, and collective trauma (school shootings or firefighters who lose teammates)

- Racial trauma (microaggressions or police brutality against Black Americans)

- Cultural trauma (unequal access to care, housing, and food)

- Historical and broad-reaching traumas include:

– Historical traumas (the Holocaust or slavery)

– Natural traumas (avalanche or tsunami)

– Human-caused traumas:

– Accidents (sports-related deaths)

– Technological catastrophes (train derailment)

– Intentional acts (terror or terrorist attacks)

– Mass traumas (the nuclear reactor meltdown in the Ukraine or Three Mile Island in the U.S.)

Who Experiences Trauma?

While trauma can (and does) happen to anyone, it is more commonly experienced by oppressed and marginalized groups and communities. Globally, a meta-analysis of more than 160 published research studies reports that many refugees have survived traumatizing ordeals, such as witnessing deaths by execution, starvation, or enduring violence and torture. Some global regions or cultures are also more likely to experience certain types of trauma, including military action and political violence, and they have more traumatic experiences. In the U.S., Harvard public health researchers found that Hispanic and Black Americans experience more child maltreatment exposure than White Americans. They also discovered that Black Americans have significantly higher exposure to assaultive violence, such as kidnappings and muggings.

Trauma can also occur at an early age. The World Health Organization estimates that up to one billion children globally (ages 2–17) have experienced abuse, violence, or neglect in the past year. In the U.S., the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)—a leading public health agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services—finds that 26% of children experience at least one traumatic event before their fourth birthday, one in five children witness violence in their family or neighborhood, and 60% of youth have been exposed to crime, violence, and abuse, either directly or indirectly.

What Is Re-traumatization?

Re-traumatization also matters and is something trauma-informed work aims to prevent.

Re-traumatization occurs when a person or group is reminded of the original traumatic event, causing them to re-experience the trauma as if it were happening at that exact moment. Re-traumatization can be obvious or not, is usually unintentional, but is always hurtful because it deepens the person’s, group’s, or community’s struggle and symptoms.

What constitutes a reminder varies greatly based on person, place, and event. Reminders can include stimuli related to the original trauma, such as similar smells, colors, location, or weather. They can also be innocent or appear completely unrelated. For example, a person who endured a mugging might relive that trauma every time they walk past an alley or smell scents that were present that night (such as food or cologne/perfume). But they can also have their trauma invoked while at work by a colleague who accidentally points their finger (it reminds them of the gun) or while writing a report when the sun touches their laptop and casts a shadow (it reminds them of the attacker’s shadow).

Technology-wise, an invoking reminder can be app notifications about a previous post or year-in-review (like when a parent was reminded of their deceased child) or a newsfeed about war or related traumas. Asking people to tell their stories, which is common in design, can be re-traumatizing, not just for the participant but also for the researcher(s).

Impact: Another Reason Why Trauma Can’t Be Ignored

Understanding trauma includes understanding how those who experience it relate to it on a deeper level. Many who experience trauma go on to live their lives with little (if any) difficulty, while others endure lasting impact. The latter group experiences profound and life-shaping consequences, including intense physical, psychological, and physiological harm (such as heart condition, anxiety, and sleep disturbances).

The experience of trauma invokes our innate fight or flight mode: Our emotions are heightened, we become on edge, and our bodies prepare to fight or flee. For some, this natural reaction goes away with time, but for others, it remains at least partially invoked; this is often the case for those who experience multiple traumas. Their automatic response never fully shuts off, leading to a compounding effect. Over time, people or groups who live in this constant survival mode typically react in one of three ways:

- becoming shut off and disconnected,

- feeling hopeless and sad, living in an almost constant state of anxiousness and fear, or

- they become resilient and feel they have no choice but to move on (not through their traumas).

But resiliency isn’t always good. The most resilient people or groups are often the ones who are also marginalized or disenfranchised. A trauma-informed approach suggests that instead of forcing people to become resilient (in the face of [repeated] adversity and trauma), we can and should change the systems they interact with (like technology) so they don’t have to work so hard.

Trauma can forever change how these people or groups see and interact with the world around them, forcing them to construct a new understanding of how the world works. This sense-making then guides and informs their feelings of safety, trust, empowerment, and identity when interacting in the world and with institutions and people (such as technology, government, and strangers). For example, imagine someone is hit by a car as a pedestrian in the crosswalk. Going forward, they may distrust all drivers or vehicles and feel unsafe when walking or attempting to cross the road in the future (if they are willing ever to do it again). This sense-making can also inform future life choices, even seemingly unrelated choices, which in today’s digital age, include how and what technology to use, or if at all, and for what purpose.

Trauma is very contextual and individualized. What is traumatic to one person might not be traumatic to another. Trauma responses vary greatly depending on lived experience (such as trauma history), biopsychosocial factors (such as identity and capacity for coping), and larger interacting sociotechnical structures (such as political, economic, and technical). For example, SAMHSA finds that those who experience childhood trauma are at greater risk for various mental and behavioral health adversities throughout development than those who don’t. Across all age groups, SAMHSA also finds that rates of trauma symptoms are higher among unsheltered people.

Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recently commissioned novel guidelines that acknowledge and attempt to address the impact of trauma, specifically on mental health. This shift acknowledges and attempts to address the social and economic factors that affect people, groups, and communities that can induce trauma or re-traumatization, including discrimination and human rights violations. These guidelines are a critical and timely move from biomedical approaches toward a human-rights and trauma-informed approach to care.

How to Become Trauma-Informed

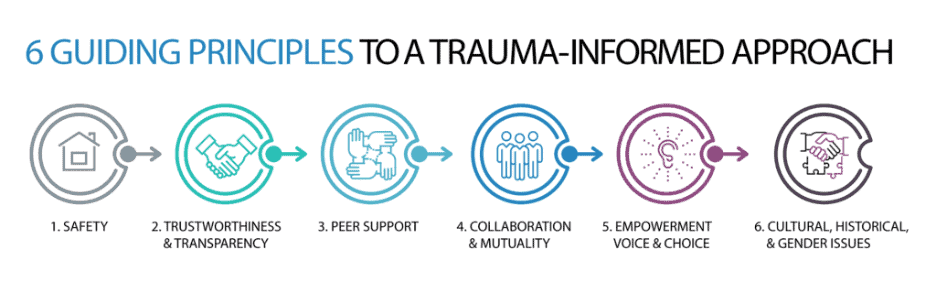

As user experience researchers and designers focused on care, our shared vision is to live in a world in which technology is helpful and avoids harming anyone. We believe tech can proactively prevent or reduce trauma and that trauma is a community issue, not an individual one. Our work is guided by and applies SAMHSA’s six trauma-informed principles (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Six Guiding Principles to a Trauma-Informed Approach (Credit: Centers for Disease Control 2020, based on SAMSHA 2014).

Following are the six principles and design-related examples for each principle:

- Safety includes both physical and emotional safety. Determine and set up locations with care (physical) and pay attention to signs of discomfort in participants so you can respond with care (emotional). For an app, safety might mean defaulting to not sharing a person’s location without explicit consent (physical) and inclusive language (emotional).

- Trustworthiness and Transparency. Create clear explanations to set accurate expectations about all actions, including what will happen, why, and with whom, so people can make informed decisions. When we make transparent design and research decisions, they help build and maintain trust. This applies when individuals decide whether to consent to, and throughout, research and when choosing to fill out an online form.

- Peer Support involves the support of others who have similar lived experiences. Peer support is critical to establishing safety, building trust, fostering collaboration, and promoting healing. In research, this might look like paired usability testing where a research participant can bring a friend or loved one along. Online, this could be a forum where individuals can connect with others in a safe and supportive manner.

- Collaboration and Mutuality is equity and partnering with mutual respect. Importance is placed on giving people options, partnering with them (not doing for them), and leveling off power dynamics. In research, this principle can be thoughtfully planned co-design work or participatory design sessions that center around the intended audiences. On a website, this may mean giving people options to explore and move through content (such as not forcing someone to watch a video to get the information they need but also offering the information in text).

- Empowerment, Voice, and Choice build on people’s strengths to find answers for themselves and leave space for options. In technology, intended audiences should have a say in any product or service that will impact them. The rallying cry of the disability community is relevant here, “Nothing about us without us.”

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues are interwoven throughout the trauma-informed approach and are about more than interconnected identity. Notably, it reminds us that to be trauma-informed, one must be equitable, just, inclusive, and considerate of all current and historical sociotechnical structures or events that can impact and cause trauma. UX researchers need to be thoughtful when approaching other groups that they are not a part of and work with experts to plan interactions with care. Designers should consult the intended audience to avoid harmful missteps in design output. We see this happen so often for those with low or no vision. Without considering the needs of various groups, we can cause harm and re-traumatization.

Together, these principles make up a trauma-informed approach. They are not in a required order, are naturally interconnected, build on each other, and are flexible enough to be used in any setting. There is no checklist to follow because flexibility is key, and each situation is nuanced. In applying SAMHSA’s six principles, designers and researchers realize trauma’s impact on people, recognize the signs of trauma when they surface, and respond with appropriate action to resist re-traumatization. We suggest using this framework because it has been created, validated, and used by the social work field for many years.

The Foundation of Trauma-Informed Design

The good news is that some of the underpinnings of a trauma-informed approach may be familiar to designers. Trauma-informed design work is not about learning a whole new design system. The following are the foundations that are needed to practice trauma-informed design.

Good Usability

It’s tough to imagine a website, app, online form, virtual reality, or other technology experience being trauma-informed if it is hard to use. Any work you can do to increase usability by following established user experience principles is an essential start to becoming trauma-informed. For example, the classic UX book Don’t Make Me Think, by Steve Krug, emphasizes traditional user experience ideas, including reducing cognitive load. The Nielsen Norman Group offers other valuable UX heuristics, such as offering users control and freedom. Following these principles would support anyone, especially someone who has experienced trauma.

Start with what you know. Make the tech experience as easy to use as possible. This can be evaluated with familiar research methods like usability testing and heuristic evaluation. Once it’s easy to use, you can begin to make it more trauma-informed.

Positionality for Project Teams

Next, consider how your team can set themselves up to become more trauma-informed by doing some critical self-reflection. Critical reflection is core to social work practice. It is the process of questioning one’s own assumptions, presuppositions, and meaning-making. It is essential for accountable, ethical, and quality practice. Similarly, to be a trauma-informed designer, you must genuinely and authentically know yourself and what you bring to the table—for better or worse. You must know all the ways you can, directly and indirectly, cause harm, such as by unconscious biases you are (often accidentally) weaving into your design or by any lived experience you may share with research participants.

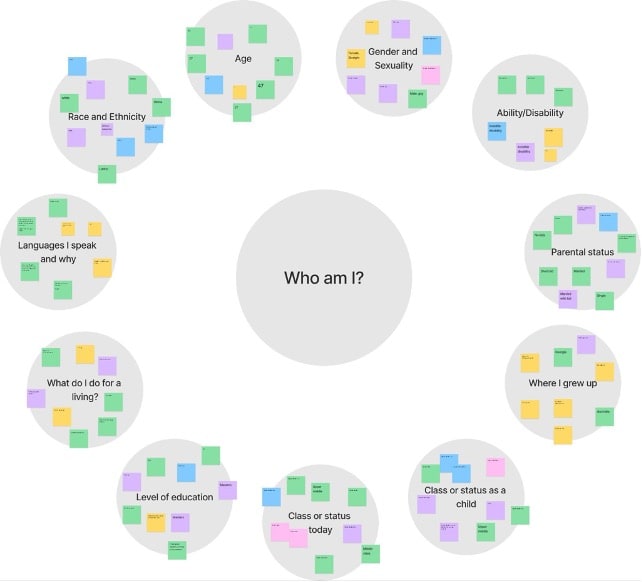

Positionality exercises are also extremely relevant to trauma-informed design work and have recently become more popular as the design world has become more aware of power dynamics within technology (Figure 4). For example, when applying the principle of collaboration and mutuality, how can you mitigate hierarchical power dynamics if you aren’t even aware of them? How can you consider the needs of a particular group if you don’t recognize who you are excluding? Utilizing positionality exercises and participating in critical self-reflection will help you realize all of this and design better, more trauma-informed technology.

We have used positionality exercises with our project teams and in workshops to identify what essential perspectives may be missing (Figure 4). This article by Lesley-Ann Noel and Marcelo Paiva, Learning to Recognize Exclusion, includes a valuable and easy-to-implement exercise to help people recognize exclusion.

Figure 4. A digital whiteboard artifact from a reflective design workshop, based on the positionality exercise developed by Lesley-Ann Noel.

For example, in a recent project, we aimed to help people who receive government healthcare learn about mental health and substance abuse services. By doing this positionality exercise together, our team realized that only one of us had ever benefitted from this type of government assistance. The exercise helped us recognize whose voices would be missing and brainstorm ways to include these essential perspectives. As a result, we consulted with subject matter experts and prioritized individuals with lived experience of government assistance as participants in each stage of the design process, from generative to evaluative work. Beyond traditional usability testing, content testing of text and images was also very valuable in iterating and developing useful, relatable, and accessible health information. The final website centered on meeting the needs of our priority group by using plain language to explain how to set up appointments and emphasizing how to find free support services.

Trauma-Informed Research

We all know that research is essential to user experience design. That research should be trauma-informed. Researchers in the social work field have been conducting trauma-informed research for years. We don’t need to reinvent it, but instead, we should look to what others have learned is best to avoid. At best, a misstep can result in an uncomfortable session and, at worst, a re-traumatizing research session. You can apply the six principles to setting up and conducting your research with activities, including but not limited to these:

- Setting clear expectations that are mutually agreed upon.

- Thoughtfully consider how you are executing and managing ongoing consent.

- Have your interview guides and surveys reviewed by a clinical trauma-informed expert. Yes, surveys can and should be trauma-informed, too.

- Creating a care plan for participants and researchers.

- Providing choices for participants. For example, see how this hospital navigation research team offered an alternative choice to participants who were uneasy with their mobility request.

- Following through with what was agreed upon about incentives, resources, and information sharing, etc.

We encourage you to iterate on your research process and make it more trauma-informed before, during, and after it ends. We do this all the time. For example, during a recent research project, while conducting usability testing with recently incarcerated adults, one of the authors realized that the opening questions in the conversation guide were too broad, leading to the unnecessary re-telling of traumatic stories. As mentioned earlier, this could be harmful to not only the participants but also the researchers. She called the other article’s author as a subject matter expert for advice. We adjusted the guide accordingly to ensure the conversation focused solely on feedback for the prototype at hand and limited the opportunity for oversharing or re-telling.

Like the participants in our example, each group you conduct research with will have different needs, calling for a nuanced approach to every study, particularly if it involves sensitive topics. The better you can understand your participants and the ways they experience trauma, recognize their traumatic responses, and apply trauma-informed principles to your research protocol, the more prepared you will be to meet the needs of those you serve.

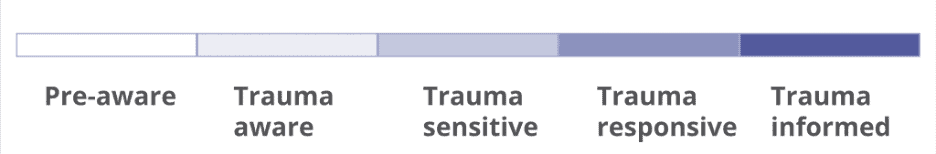

A Continuum Including Complementary Efforts

Becoming trauma-informed is on a continuum. Genuine change takes time. One does not become trauma-informed overnight or after one training. This is a multi-year and iterative process. We have been doing this work for over a decade and continue to learn something new daily as technology and trauma-informed approaches evolve. One begins by becoming trauma-aware (from pre-aware), and with deliberation and strategic training, one concludes by maintaining trauma-informed. The Missouri Model is a helpful guide and provides concrete examples of how to move through this process (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The continuum of being trauma-informed, as developed by The Missouri Model (2014).

Becoming a trauma-informed designer or researcher aligns well with diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) change. Like becoming trauma-informed, strategic and critical DEIA change takes time, but it is work worth doing. Research finds that when companies and employees fully embrace DEIA values, performance improves, and employees stay. If we apply DEIA research and the growing body of trauma-informed research from clinical settings (such as how trauma-informed care decreases cost and increases revenue), we can envision similar benefits from trauma-informed technology for users, designers, and society to improve users’ well-being and equal access to services.

Cultivating culturally sensitive and harm-reductionist technology ensures we develop solutions that positively impact society. The best way to nurture and support technology’s diverse users is to create and sustain design work that ensures equity and inclusion and proactively prevents (further) harm so that all people can participate and thrive.

Anything you do to help a larger group of people access services and products will move you along the trauma-informed spectrum. Reducing the reading level of text with plain language and using the language of that community or group is a first step. Ensuring that the mobile experience is fantastic is another step. If you follow design and code best practices for accessibility, you are already heading in the right direction; now, you can begin to consider your website, app, or other digital experience through a trauma-informed lens.

Continual Learning for a Sustainable Career

As we discussed previously, becoming trauma-informed is a process that doesn’t end. Like cultural competence, it is a moving goal toward which we aim. It helps to learn along with others, as it’s nearly impossible to sustain trauma-informed work by yourself. As we work toward becoming trauma-informed designers, researchers, and organizations in tech, you can find peer support and connect with others.

Start by reading SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Once you thoroughly understand the principles, you can move toward application and connect with other experts as you work. Learn more about trauma-informed design and technology by exploring the resources at tidresources.org. Find community by joining people worldwide for a monthly discussion on trauma-informed design ideas in the Trauma-Informed Global Learning Group.

Concluding Thoughts

Now more than ever, given that we all experienced the COVID-19 pandemic and the world is only getting more (not less) complex, we must do our design work with care. We must also fully understand the needs of those who use our products and services, especially as they relate to trauma. Just as we would never ignore a soaked friend on our doorstep, we cannot pretend that trauma isn’t a part of most people’s lives. Trauma must be considered in design. It’s essential to remember how common trauma is, and it is imperative that we respond in ways that resist re-traumatization, which notably includes creating more inclusive and positive experiences for all using trauma-informed approaches.

Thanks so much for reading our article. If you’ve enjoyed it and feel that you’ve learned something of value, please share it so that others can learn from it, too.