In this participatory culture, technology innovation is increasingly driven by enthusiastic fans. The recent global success of Pokémon Go as a revolutionary augmented reality mobile game is an example of fan innovation. It began as part of videos released as April Fool jokes in 2014 by some Google employees who were also enthusiastic Pokémon fans to promote the Google Maps app. After seeing the video, the Pokémon Company thought that the augmented reality game would be a great concept to expand the Pokémon series and then started the collaboration with Nintendo and Nitantic (a Google company). The rest is history.

It is not random that a fan innovation rekindled an epic game with 20 years of history and helped it reach an even wider user community and younger generations. As a matter of fact, fans are often included in the process of game development. On the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, indie game developers raise money from their backers, most of whom are their current and potential fans. They also use the campaign as a means of communication and an opportunity to receive user feedback for design improvement before release. For example, Camouflaj originally was only planning to release the game of République in the iOS version, but later expanded to include the desktop versions in both PC and Mac as well as an Android version after listening to their fans. In response to their willingness to work with fans, their crowd-funding campaign took off and reached its goal successfully.

Why We Want to Work with Fans

I didn’t realize the power of fans for product design and innovation until I came across the South Korean boy band Super Junior. As a household band in East Asia, Super Junior was the 2015 winner of Choice International Arts for Teen Choice Awards in the U.S. Formed by SM Entertainment in 2004, they have had three successful world tours since 2011 supported by global fans, many of whom are young girls from East Asia to the Middle East, Europe, and North and South America.

As we all know about cross cultural UX, it is challenging to succeed on the global level. So how could a group of flowery-styled boys who mostly sing Korean songs mixed with random English phrases attract so many fans globally? I was puzzled.

The answer is simpler than I thought: social media-driven fan activities have played an important role for the global circulation of Korean Wave products like Super Junior. Indeed, many Korean Wave researchers acknowledged that the fandom matters to the international rise of K-pop (Korean Pop). Because of the enthusiasm of those global fans, K-pop became a major driving force of South Korea’s economy for the past decade. This phenomenon was particularly catalyzed by the rapid growth of social media platforms and networked communication.

No wonder Super Junior was also the winner of Choice Fandom in 2015, with the support of their large fan base. The fans’ nickname, ELF (for “Ever Lasting Friends”) is well deserved: When the band released their new song “Devil” in July 2015, thousands and thousands of ELFs worldwide were spontaneously organized by the leaders of the fan community to promote it. They downloaded the song from iTunes again and again, watched the YouTube music video non-stop, and clicked like crazy every day to vote for the band for the Teen Choice Awards. The fans pushed the new song to the No.1 rank on the iTunes charts in ten countries and regions on the first day of its release.

Clearly, fans are committed and loyal users who can amplify their actions and preferences when they work in concert, compared to individual users. They resonate well with the cultural values and identities represented by the fan objects they admire. In the case of Super Junior, this idol-centered K-pop band combines cheery music, well-synchronized group dance, polite demeanor, and attractive looks and fashion, which represents the values and tastes of the urban and suburban middle class across the world. It matches the imagination of college-aspiring young girls for their future loved ones. For example, back in 2009, the now successful Miss Universe 2015, Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach, who came from the Philippines, tweeted about her dream of having some team member of Super Junior be her boyfriend.

When they become fans, people like to invest more in their fandom and get more involved in their fan communities, ranging from interacting with the fan object, participating in fandom-related events, contributing to the causes represented by the fan object, and purchasing related products and accessories.

Fans are also the brand ambassadors who would convince their friends to try something they strongly believe in. Loyal fans will fight for the survival of the product they enjoy. Super Junior’s Teen Choice Award is such a case. In recent years, Super Junior faced fierce competition from newer bands represented by the same company, such as Girls’ Generation and EXO. Rumors said that more company resources were diverted away from Super Junior to support other bands. Concerned about the loss of company resources and support for their favorite band, the global ELFs made their favorite band the winner of Teen Choice Awards for the first time with their coordinated and devoted efforts.

Who doesn’t want to work with this kind of fan base? They are the enthusiastic users we dream to have for technology design.

How Fans Help Product Innovations

Ironically, fans and fan communities are seldom studied for technology innovation, even though earlier studies of participatory culture began from the context of fan communities, as illustrated in the work of Henry Jenkins and Nancy Baym who wrote about the creative practices of TV fans such as fanfiction and fan video production in the 1990s.

Two case studies of fan innovation on social media illustrate the contribution of fans to technology innovation. Both are from East Asia where fan power is more recognized and where fan economy is promoted.

Beyond the entertainment industry, the rising fan culture and new trends of social media-driven fan activities in East Asia (South Korea, China, and Japan) greatly changed local design practices. Creating and fostering fan communities has become part of the design and innovation process for many IT innovators and entrepreneurs there. According to one popular anecdote widely circulated among the Chinese fan community of Super Junior, the CEO of SM respects fans’ opinions. He once chatted with a few teenager fans outside an SM-hosted concert in China to learn about what idol traits they wanted to see from the SM bands.

Fans are devoted needs experts

While a great user experience helps users who adopt a product to stay with it and continue using it, even the most extensive user research could only study a limited number of users and lifestyles. To effectively address vast user needs of everyday life in a globalization age, I recommended in my book, Cross-Cultural Technology Design, letting users participate in and complete the design cycle in their own contexts.. Compared to the designers who are good at coming up with solutions for defined problems, users are needs-experts who have more insider knowledge. When users bring their various “need expertise” to connect with a designer’s “solution expertise” (using the terms from von Hippel), new design solutions often click. They often help designers further customize and localize a product into their everyday life to fit their lifestyles. I call this user localization.

As passionate users, fans are more motivated to help shape (and then support) the product they enjoy than ordinary consumers. In a recent Wired article, the Chinese electronics company Xiaomi (Chinese meaning: millet and rice, or a staple of life) was lauded as an example of a company to emulate. In other words, “to copy China.” This international tech company sold 160 million cell phones in the five years since it was founded in 2010.

A big part of their success can be attributed to their loyal fans and their solidarity. Xiaomi launched the fan community for their products one year before they released the first phone model, Mi Phone. Six years later, they have a sophisticated system of global fan communities through multiple channels, including web-based user forums, microblogging accounts on Twitter and Sina Weibo (Chinese Twitter), official accounts on WeChat (a popular mobile chat and social networking service app in China), and groups on the QQ messenger.

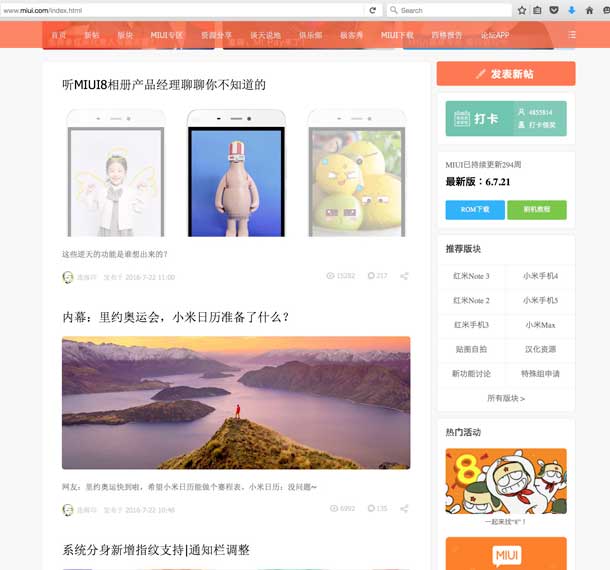

Figure 1 shows the homepage of the website for MIUI, an Android-based firmware, where fans of Xiaomi gather. In the screen shot, the second teaser story, posted on July 22, 2016, features the way Xiaomi responded to a user’s request to add a feature of the Olympic Game Schedule to the Xiaomi calendar, an example of how “need expertise” is perfectly matched with “solution expertise.” In addition to those ad-hoc interactions between fans and developers, Xiaomi started a tradition of “Orange Friday.” From the founding days of the company, every Friday Xiaomi releases new updates to the ROM of MIUI, and openly invite fans to give feedback via user forums.

Like Super Junior’s ELFs, the fans of Xiaomi have their own official name, Mi Fan. (Chinese meaning: rice noodle). Following Xiaomi’s lead, many Chinese mobile phone manufacturers started their own fan clubs. For example, the fan club for HuaWei mobile phones was established in 2012, which is called Hua Fan (Chinese meaning: pollen). Among all those official mobile phone fans, the fans of Xiaomi are famous for their solidarity; rumor says that one needs to be very careful when critiquing Mi Phones on social media platforms as Xiaomi fans will fight zealously for the reputation of Xiaomi.

Fans are innovation collaborators in identifying minimum viable products

With the rise of innovation trends for the minimum viable products (MVP), fans and fan communities are even more important for innovators. A loyal fan base not only helps to kick off successful initial sales, but also serves as lead users and “citizen designers” who test beta versions, provide feedback, and participate in product upgrades throughout the whole design cycle. Indeed, Xiaomi began to nurture its fan community when they were still working on the MIUI. Those loyal fans stood by Xaiomi’s side as they went through the different stages of development until the release of the first phone model, Mi Phone. 100,000 phones were sold in three hours partially due to the enthusiasm of the fans. Later Xiaomi set records for flash sales for later models of the Mi Phone with fan support, including selling 150,000 phones of one model in 15 minutes and 300,000 units of another model in four minutes.

Fan communities serve as a bridge to coordinate random and idiosyncratic “local innovations” into more structured and organized efforts, making local demand for product upgrade and innovation more visible. Hugo Barra, the VP of Xiaomi and former vice president of Google’s Android division, commented in Wired on this type of community-oriented innovation strategy: “The Mi community is hugely important and is inseparable; …You can’t replace the community with any marketing strategy in the world.”

Developing a Fan Base with Unique Cultural Values

Fans are particularly precious for start-up companies because they are a group of devoted users who share the mission, ethos, and cultural values of the company. In this social media age, those devoted fans are often passionate promoters of the fan object they enjoy and eager to spread the fandom as much as they can. They are key opinion leaders who have the leverage to influence their peers and followers on social media platforms. For social media-based high tech products, fostering a fan base is a strategy for growth hacking. As the fan community forms and continues to grow, the innovation the start-up introduces is able to grow and thrive in a healthy ecosystem, which will further attract new users, creating a snowball effect.

To develop a fan base, start-up companies need to think of what cultural values they want to promote with their fan base and how those values could be visually represented through mascots or objects related to key products. Sometimes mascots or accessories that symbolize the taste and style of products are more effective to convert window shoppers into fans who could be potential users later. This is what LINE has been doing.

This top Japanese mobile chat and social network service giant—which held dual Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) on the New York Stock Exchange and the Tokyo Stock Exchange in July 2016—was not content with their rising online presence in the social media landscape of East Asia. To extend the reach of their friendly online chatting space to the offline world, the company creatively branded the characters they designed for their virtual stickers and emoticons into new lines of “LINE friends” accessories, cartoons, and games. The two famous characters are Cony, an emotional and jovial rabbit, and Brown, a serious but sensitive bear. They later opened brick-and-mortar LINE Friends Café and Store in cosmopolitan areas of East Asia and North America including Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong, Taipei, Shanghai, and New York City to reach fans face-to-face.

I conducted international user research at a LINE Friends Café and Store in Seoul (see Figure 2) last year. At the three-floored store in a fancy shopping district, LINE users and fans gather for coffee and sweets and buy cute and adorable accessories including plush toys, t-shirts, cups, chargers, stationary, cookies, and coffee, each enhancing the branding image among current users and expanding the appeal of the LINE app to potential users. To more effectively reach their target users and uild their fan base, LINE wisely collaborates with brands popular among their potential users; they collaborate with Uniqlo for T-shirts, Missha and Innisfree for lipstick, foundation, and other beauty products, and with Swarovski for jewelry.

A LINE Friends Café and store is often a tourist destination. During my visit I saw quite a few tourists from Hong Kong and mainland China who were excited to take pictures with LINE characters in the store; a selfie with the giant toy Brown was a must.

Getting Fans Even if You Don’t Have Users Yet

At the time of this writing, LINE is still blocked in China. However, a large fan base for the app still formed after LINE opened its first LINE Friends Café in Shanghai last summer, followed with more than a dozen stores in other cities. The cute accessories of LINE friends are very popular among Chinese women and girls, who circulate many pictures on social media platforms.

Olympic-themed toys of LINE characters are promoted through the partnership with a popular fast food restaurant brand appealing to Chinese children and young generations (see Figure 3).

Sooner or later, those fans of LINE characters will probably become LINE users and innovate together, driven by their passion, creativity, needs expertise, shared style taste, and cultural values. This could be a strategy for Facebook and others eager to enter the Chinese social media market.

As Hugo from Xiaomi put it, “We don’t care about selling phones but about getting as many users as we can.” When one cannot get users due too various political, economic, and technical reasons, maybe one can get fans first.

Cautious Reminders About Working with Fans

It is not easy to work with fan communities for innovation. From a company standpoint, having a devoted fan base for a product is a double-edged sword; the strong fan support received during the initial launch period can turn into unwelcome resistance to a change of company strategies later as the fan communities grow bigger and more powerful.

In the case of Super Junior, SM learned to coordinate with their fan communities carefully and drive cooperation. For example, they chose to partner with the leadership of bigger fan clubs to influence the decision-making process of the fan communities.

As the product grows and expands, the makeup of the fan community also changes. Fan strategies need to respond to such kind of change. Recently Xiaomi began facing declining sales due to the ever-changing cell phone market and also the changing fan community. Their astounding sales records were made primarily by technology geeks, but their expanded user community is made of more common consumers who were attracted by Xiaomi’s legendary success. The fan strategies that once worked well for geeks don’t seem to be as effective for common consumers.

Will You Create the Next Pokémon Go?

As a researcher who studies user innovation in this increasingly globalized world, I see ways that the UX community can use fans and fan communities as an unconventional force propelling technology innovation. Nintendo and the Pokémon Company made a huge success this summer by transforming fans’ contribution into a ground-breaking game worldwide. How about your company?

Huatong Sun is associate professor of Digital Media Studies at the University of Washington Tacoma. Author of the award winning book “Cross-Cultural Technology Design” (2012), she studies how to design and innovate for usable, meaningful, and empowering technology in this increasingly globalized world. She is once again working with Oxford University Press for her new book on global social media design. Twitter: @huatongs