Do you believe you have a relationship with your city, town, or neighborhood? Is it a good one? Are you happy to live and work there, or do you feel it’s time you left?

Your interactions with the place you live are not dissimilar from the interactions you have in your relationships with other people or with brands, companies, and organizations. You may pay taxes in order to have access to a good school system, or you may contribute fees for the ongoing maintenance and improvement of your residential development. The nature of this relationship can be characterized as a service, where a value exchange occurs, similar to services such as dry cleaning or dining out.

Envisioning the Future of the Bronx

It is the service nature of the relationship between a city and its people that we explored in our participation in an ideas competition in 2009: Intersections: The Grand Concourse Beyond 100. The international competition sponsored by the Design Trust for Public Space and the Bronx Art Museum in New York wanted visions for the revitalization of the long neglected—but once beautiful—Bronx Grand Concourse, a four-mile stretch of boulevard originally inspired by the grandeur of the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

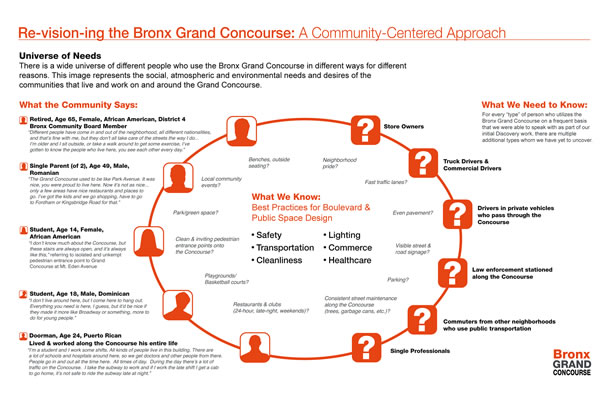

We were intrigued by the challenge and decided to enter the competition, but were clearly out of our element, competing against international teams of architects, urban planners, and interior designers. The ideas of most of the other 400 entrants focused on the physical aspects of the Concourse itself (for example, the strong winds or the pollution problem). Many referenced global trends (such as sustainable local farming) or capitalized on technology (for example, integrating a pervasive, ubiquitous wireless system along the Concourse). None, however, represented the human needs, values, and overall experiential elements of what it means to interact with a space as we proposed in our submission Re-vision-ing the Bronx Grand Concourse: A Community-Centered Approach (see Figure 1).

Among hundreds of submissions, our proposal made it to the final seven. We were then asked to expand our ideas for the opportunity to compete for first place in a final jury evaluation. Our work was featured at the Bronx Art Museum for six months.

How did we—lowly experience designers—progress so far in the face of actual architectural and urban design concepts? There were two reasons: we were the only entrants to actually focus on the “users” of the Concourse; and, equally important, we reframed the design problem to be more about the service relationship between the city and its people.

Reframing the Design Problem: City as Service

Service design is the activity of planning and orchestrating all tangible and intangible elements of a service—including people, processes, time, communications, objects, technology, infrastructure, and space—to create an effective experience. Unlike traditional user experience work, where a designer is focused on the user and the interface, in service design, a service is only effective if all elements are coordinated.

Applying this service framework to the Bronx Grand Concourse immediately recalibrated the lens through which we viewed the competition and that which we typically used in our UX work. Instead of the design problem revolving around whether a park should be added or speed bumps should be higher based on people’s needs—essentially, the physical and functional attributes of the space—we realized we needed to think even more broadly. We needed to answer the question, “What should the service relationship be between the Bronx Grand Concourse and the residents of the Bronx?”

Immersion and Observation

We quickly immersed ourselves in the Bronx to experience first-hand what it meant to interact with the Bronx Grand Concourse, and made observations along the way. We quickly noticed the diversity of uses the Concourse has for people: they walk along it, drive along it, shop along it, and access medical care along it.

It became apparent that our original focus on envisioning the service relationship between the Concourse and residents was inadequate. Rather, the city needed to account for all those who interact with the Concourse (shop owners, drivers, police, students) and for all their interactions with the Concourse. When designing services, the interconnectivity of all the elements of that service need to be fully orchestrated, otherwise the service fails.

Who Is Involved in the City-to-People Service Relationship?

When we realized the design problem was broader than city-to-resident and rather was city-to-people, our first goal was to understand and document the diverse constituents involved in this relationship:

- Residential

- Educational

- Safety and security

- Healthcare

- Civic and government

- Employment

- Transportation

- Entertainment and recreation

- Cultural

- Commercial

Because the success of a service relies on the orchestrated interactions of all people involved, the service is a result of a co-created experience. In a restaurant, without the customers or without the cooks, the service inherently won’t happen. The same is true of the Bronx. With any of the above constituents, co-creation is necessary for the service to be a success. In education, it’s the teachers, administration, students, and parents. In commerce, it’s the shopkeepers and customers. The people of the Bronx have a dual role as both “users” of the city and creators of the city: the Bronx is its people, and with that there is a reciprocal responsibility for making the relationship a success.

What Is the People’s Vision?

Once we knew the various people involved in what would be the future of the Bronx, we needed to understand their needs, values, behaviors, and perspectives. We spoke with more than 130 people along the Grand Concourse in five distinct locations (see Figure 2). Our questions included:

- Why are you here today?

- How often and for how long do you come to the Concourse?

- What do you like about it? What don’t you like?

- What is one word to describe the Concourse?

- How old is the Concourse? (to understand awareness of the Concourse’s history)

- What are your skills and interests?

- What are the top three areas you’d like to see improved here?

- What communities do you identify with?

We prepared a few research materials to help answer the above questions, including a survey, a prioritization board where participants could select the top features of the Concourse they’d like to see changed, and a Bronx map where they could explain where they live, work, or visit.

To ensure we achieved a holistic and diverse perspective, we also spoke to:

- A professor of African-American studies and an education policy director for the educational perspective

- Artists and an author for the cultural perspective

- A women’s housing executive and Concourse advocates for the residential perspective

- An urban planner and an economic development CEO for the civic perspective

- Teen arts council members for the youth perspective

We documented our findings as a set of insights (see Figure 3).

What Should the City Focus On?

Given that this was solely an ideas competition, we were not necessarily responsible for showcasing a tactical list of detailed recommendations. Rather, our goal was to illustrate the need to view the future of the Concourse as the integrated and systematic outcome of a variety of issues to resolve (see Figure 4). For example, safety was the area most in need of improvement; one specific area of opportunity would be adding street lights. Adding street lights, however, would have an environmental impact, a maintenance impact, and a financial impact. We needed the city and its people to begin to understand that improving the city-to-people service experience can’t be done by fixing individual issues without an awareness of the implications elsewhere. Service design, much like systems thinking, is the effective orchestration of all facets of the experience.

Becoming Co-Creators

If you’re wondering whether we won the competition, we made it to the top seven but did not place in the top three. We honestly didn’t expect to win, and were surprised at how far we had progressed. Regardless, the competition quickly became something bigger than a jury-evaluated contest; it had become something we felt personally invested in. Through our participation in this competition, we became part of the city, co-creators of that experience, and we were viewed as people who could make change happen. A common question people would ask was, “So are you guys going to do anything with this?” Our efforts ultimately became more about the responsibility we felt to effectively communicate the needs of the people and less about us winning.

Lessons for Our Day Jobs

Our participation in the competition taught us lessons that we can apply in our experience design work:

1. Reframe design problems as service opportunities.

Rather than assuming the design issue is small and siloed (“improving the navigation on the portal”), reconsider what you’re working on as part of a larger service offering, broader and more holistic (“understand how best to enable employees to do their jobs effectively”).

2. Be flexible.

Our original assumptions, problem definition, hypotheses, and how we approach our work may need to change. The more flexible you are to adapt to new insights and information, the more likely your designs will be accurate and will stick for the long term.

3. Understand all experiential elements in concert.

Once you broaden the design problem to be a service opportunity, you can no longer assume your view is solely about a user and the interface, and need to stop thinking about user-centered as the appropriate mindset and approach. Understand and document all people who may be involved (these will likely be internal and external), processes, and tools. Also, don’t forget about the intangible aspects; the emotions that an experience elicits from someone are as important as the functional elements.

4. Co-create.

Include the diverse constituents in the design process and ensure you are capturing insights about their role in the service, their motivations, behaviors, and needs, and provide them the opportunity to participate in any design iterations and validation. Also, keep in mind your own role as a designer within the service experience; remain aware of the biases you may have and how your presence and involvement can impact the service design.

5. Get to ideas quickly and iterate.

The spirit of service design requires exposing our processes to others, involving them, and quickly turning insights into a tangible idea, concept, or design for validation and iteration. By doing this, you show value more quickly and socialize your thinking with others who need to accept those ideas, thus avoiding issues arising later.

Final Words

The world is becoming much more heavily reliant on services for reasons that range from cost-effectiveness to sustainability. Whatever that experience entails—urban, mobile, retail, product, software, spatial— applying a service perspective is critical, and user experience and design professionals are primed for making these service experiences effective服务设计 是一个新兴领域,用户体验专业人员和企业思想领导者可以借助它增强其工作的影响力。2009 年,MISI 公司参加了一个国际设计竞赛,目标是重新振兴长期被忽视但曾经一度非常美丽的布朗克斯大广场。我们不适合与包含建筑师、城市规划者和室内设计师在内的国际团队进行竞争。但我们是唯一在聆听和了解广场“用户”心声的入围者。最为重要的是,我们重新诠释了设计问题,使设计更多地关注城市与民众之间的服务 关系。

这篇文章介绍在构想 4 英里长的布朗克斯大广场时采用的整体性、面向服务和以社区为中心的方法,以及哪些因素促使设计大赛赞助商(Design Trust for Public Space 和布朗克斯艺术博物馆)认可这是最佳提案。这个故事有趣的地方在于,可以将城市本身作为“服务”展示给其民众,以及这种观念转变所带来的结果。随后,我们将这次竞赛中所获得的经验应用于我们的日常设计工作中。

文章全文为英文版サービスデザインはユーザエクスペリエンスの専門家や業界が、リーダー達がその仕事のインパクトを高めるために活用できると考えた新しい分野だ。 2009年にMISI社は、以前は美しく手入れされていたが長い間放っておかれたブロンクス・グランド・コンコースの再開発プランの国際デザインコンペに参加した。建築家、都市設計者やインテリアデザイナーなどの国際的なチームに比べると力不足ではあったが、我々は、コンコースのユーザの意見の聞きとりをし、そこから情報を得た唯一のコンペ参加者であった。最も重要な点は、我々がデザインの問題を市と市民の間のサービス関係として枠組を改めたということである。

この記事では、4マイルあるブロンクスグランドコンコースのプランに使われた、全体的で、サービス指向で、コミュニティを中心に据えたアプローチについて述べ、そしてどのような要因によって、このコンペのスポンサーであるデザイントラストフォーパブリックスペース(Design Trust for Public Space)およびブロンクス美術館(Bronx Museum of the Arts)に、最も優れたデザインと評価される結果を得たかを説明している。このエピソードの興味深い点は、市が自らを市民へのサービスとしてイメージする機会を得たことと、その視点のシフトから何が生じたかである。その結果、我々は、日々のエクスペリエンスデザインの作業に活かせる教訓をコンペから学んだ。

原文は英語だけになります