In the past few years, it seems that large-scale data breaches have been occurring with depressing regularity. While it’s incredibly important to establish trustworthiness in any product, re-establishing trust after it has been violated is much harder to do. There is far less room for error when dealing with a customer base that already has reason for concern about an organization’s digital security.

Examples of security breaches abound, from Target to Home Depot, to the U.S. General Services Administration, to Google’s Gmail, and more. Each organization has handled them differently—some far better than others. There is also the issue of what is reported to the public versus the legal requirements for reporting, which vary from state to state. As an example, the California state government has a very extensive online form for reporting breaches.

But what is the best way to handle such events? According to a December 2011 article in New Scientist magazine, hacking dates back to at least 1903. The first case of reported hacking took place when Nevil Maskelyne hacked a public demonstration of a “secure” telegraph system. Despite this long history, and despite the increasing frequency of incidents, the evolution of best practices for handling hacks and security breaches hasn’t kept up with the pace of the hacks themselves.

At its core, though, what more is a security breach than an error? In their timeless set of heuristics, Jakob Nielsen and Rolf Molich provide solid guidelines to follow, saying “Even better than good error messages is a careful design which prevents a problem from occurring in the first place,” and “Error messages should be expressed in plain language (no codes), precisely indicate the problem, and constructively suggest a solution.”

Indeed, a focus first on error prevention, and then—when breaches do occur—plain language, specifics, and constructive suggestions for issue resolution, likely provide the best path to increased trust. Let’s examine how three recent breaches have and have not taken that path. We will look at the cases summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Recent retail security breaches

| Vendor | Date Occurred or Discovered | What Data Was Stolen |

| Cici’s Pizza | July 2015 – June 2016 | Unknown number of credit cards from more than 135 locations |

| Wendy’s Restaurants | October 2015 – May 2016 | Unknown number of credit cards from 1,025 locations |

| Omni Hotels | December 2015 – June 2016 | 50,000 credit cards |

| Home Depot stores | April 2014 | 56 million credit cards |

Breach Prevention: Basic IT Best Practices

UX professionals are keenly aware of the benefits of error prevention versus error recovery. But when it comes to preventing data breaches, this requires an entirely different skill set. Darrell Drystek, a security researcher, puts it this way: “It is very important to parse insider risk by unintended or inadvertent actions versus willful and malicious actions.” And while it is wonderful to try to eliminate every possible error, it isn’t always possible. It is important to understand that many breaches could be caused by security program failures, such as poorly trained staffers, bad data classification or outdated protection schemes, employees with the wrong data access rights, or unclear security policies. Sadly, breaches will continue to happen.

There are several security practices that are essential in the modern enterprise. These include using software to isolate each network endpoint from each other to prevent breaches from spreading, encrypting individuals’ credit card data to make copying this information more difficult, segregating the point of sale network from the rest of your corporate network, and patching the point of sale operating systems to keep them current with known exploits. An organization also needs to create and maintain security policies that describe how to handle breaches when they do occur to prevent further attacks and data compromises.

Error Recovery: Wendy’s

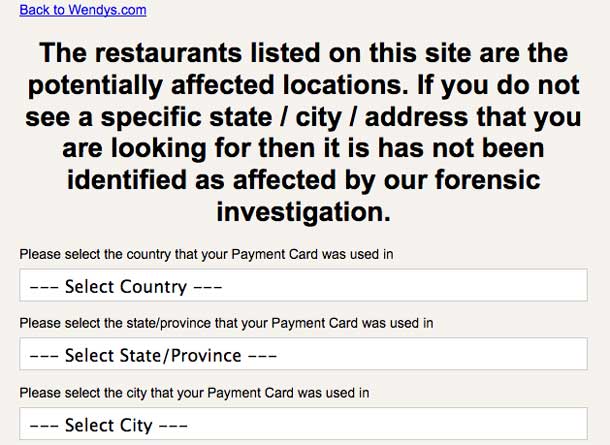

Recently, customer credit card information was stolen from the fast-food chain Wendy’s. The breach was a result of point-of-sale malware that was found at more than 300 of the chain’s 5,500 North American locations. The breach was handled on its corporate site through two web pages, one explaining the incident and one showing affected branches (See Figure 1).

Did they express the problem in plain language?

Close enough. While the statement it issued explaining the incident is straightforward, it’s written at a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 8.9, only slightly higher than the level of 7-8 recommended for communications with the general public in the United States. The statement addresses the public directly (“Dear Valued Customers…”) and includes a very clear FAQ section that seems to address questions people might actually have.

Did they precisely indicate the problem?

Not well enough. For those readers able to understand the statement, the breach itself is clearly defined. What’s less clear is whether an individual customer’s credit card information was compromised, as Wendy’s only provides information on affected restaurants. An individual consumer—particularly one who has traveled and eaten at several different locations—may not recall the specific restaurant(s) he or she had visited during the time period in question. (“Well, I was in Ann Arbor last August, and I think I stopped at a Wendy’s on the drive there from the Detroit airport, but I’m not sure which town it was in…”)

Contrast the response from Wendy’s with one of its competitors that was breached earlier this year, CiCi’s Pizza (link opens a PDF file). On a list of affected restaurants CiCi’s published, you can see precisely the locations and dates that a breach was discovered and then believed to be resolved. This goes a lot further in terms of restoring consumer trust by providing specific information.

Did they constructively suggest a solution?

Again, not well enough. Wendy’s has two basic issues, the first of which is that it took their time in responding to the breach and notifying its customers. The breach began in the fall of 2015 and was only resolved in March 2016. Second, it provided the now-standard warning to consumers, who were advised to watch their credit card statements for fraudulent activity and were given a phone number to call to learn more about complimentary fraud consultation and identity restoration services. The phone number is repeated five times within the body of the statement.

While that’s appropriate, it does little to assuage the feelings of possibly defrauded customers. And giving those consumers additional “to-dos” only adds to their mental, emotional, and time burden.

Error Recovery: Omni Hotels

Omni Hotels also recently had a point-of-sale malware security breach. Like Wendy’s, the breach affected only some hotel locations and happened under a few specific circumstances.

Did they express the problem in plain language?

While the statement it issued is straightforward, it’s written at a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 9.3, slightly higher than the Wendy’s statement and pushing beyond the bounds of readability for the general U.S. public. Further, the Omni statement is full of qualifiers like “we do not believe” and “may have” that do little to increase consumer confidence that the company is fully knowledgeable about and has addressed the issue. (As an added penalty for usability, the company uses underlining for emphasis on the web, an environment in which underlining is overwhelmingly associated with hyperlinks, not emphasis.)

Did they precisely indicate the problem?

No. While Omni does clearly say that only cards physically present at the point of sale are likely at risk, the company offers no further details about which hotels were affected and if multiple points of sale are affected (for example, Starbucks stations or on-site restaurants in addition to the actual hotel check-in desk), a detail that could expand the risk pool to local patrons instead of just travelers.

Did they constructively suggest a solution?

Not much. Like many other breached organizations, consumers are given standard advice to watch their credit card statements for fraudulent activity and are offered complimentary fraud consultation and identity restoration services. Again, this minimum and basic response has become expected and doesn’t improve customer relationships.

Error Handling: Home Depot

The Home Depot breach again involves third-party point-of-sale malware that was installed on 7,500 point-of-sale terminals in early 2014. While this seems widespread, only the self-checkout terminals in each store were infected. The breach predates the Wendy’s and Omni’s breaches by nearly two years, and the differences in approach in that relatively short time—though slight—are surprising.

Did they express the problem in plain language?

No. The Home Depot Statement is written in the third person and follows a more traditional press release format. Instead of speaking directly to the consumer, Home Depot instead speaks to news outlets expected to carry that information to the consumers. The press release itself is written at a 10th grade reading level, which is too high for the general public, but is likely appropriate for the audience of journalists for which it was intended.

Did they precisely indicate the problem?

No. The statement says the breach “could potentially impact customers using payment cards at its U.S. and Canadian stores. There is no evidence that the breach has impacted stores in Mexico or customers who shopped online at HomeDepot.com.” Again, we see little information about which stores were affected.

Did they constructively suggest a solution?

Not really. Like the others, Home Depot’s statement offers free credit monitoring and identity protection services, but only gives Home Depot’s website and standard toll-free numbers as opportunities to learn more about those services. Contrast that with the statement from Wendy’s, which consistently reiterates the phone numbers and provides information about credit reporting agencies.

Lessons Learned From Breach Recovery: Basic UX Best Practices

What do these three examples teach us about how companies should handle breaches in the future? We have specific recommendations in three areas: the way a breach notification is worded, the timing on when a breach happens, and specifics about the breach itself. Each of these needs improvement from both a UX and data security perspective.

Breach notifications: Of these, the Wendy’s model does the best job of following Nielsen and Molich’s heuristic and is the one to build upon. Though Wendy’s approach could be improved by providing next steps to those whose questions remain unanswered, its approach is superior to that taken by Omni and Home Depot. Wendy’s speaks clearly and directly to the consumer, provides as much detail as possible, and repeats the phone number for follow-up services. Companies affected by future breaches would be wise to follow this example.

Notification timing: Sadly, Wendy’s was the poorest of the three breaches we examined in terms of timing; there is nearly half a year between when the breach began to when it was finally fixed. This lack of response has been cited in at least one lawsuit against the restaurant chain.

Breach specifics: None of the three breaches we examined did a satisfactory job of explaining to the public the actual specifics of what happened, what data was potentially stolen, and how the company is planning on preventing this from happening again. The UX difference between the breach response by Wendy’s and CiCi’s is instructive: The former has a web form that a customer must use to inquire about the specific restaurant location, while the later provides a detailed list of dates, places, and times.

[bluebox]

Further reading

New Scientist magazine writes about a case of hacking in 1903

[/bluebox]