Our expectations as users has changed. Rather than simply reading content, we want to interact with it. We want to post opinions, share content, and distribute information. Our need to participate is spilling over into spaces we, as user experience experts, could never have anticipated.

That is unless we are already participating in these spaces, pushing content from site to site, sharing across an ecosystem of activity. But how many of us spend as much time in these spaces as our users do? And how many of us have made the shift from considering our “users” to be “participants”—active, responsive, and no longer interested in simply “using” whatever we serve up to them?

For some of us, these are not new concepts. But do we practice them in our design work? Let’s consider an extreme case that can help us start thinking about these issues: the use of social media during times of disaster. And not a simple crisis like Facebook going down or Twitter crashing. I’m talking about major crises: bombings, hurricanes, terrorism, tsunamis, war, tornadoes…

The Need for User Experiences that Encourage Participation

Using the extreme case of disaster, we can begin to consider the types of communication participants are undertaking across time and space using social media tools.

For nearly 10 years, I’ve researched, traced, and participated in multiple posts, threads, photo pools, hashtags, forums, chats, entries, and comments during countless disasters. From the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of 2004 to the downing of flight MH17 over the Ukraine in 2014, the need for everyday people to seek out information and distribute content across multiple social media channels has remained consistent. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, craigslist became an online lost and found for friends and family members in the New Orleans area. When terrorist attacks broke out across Mumbai, social media experts and participants used blogs, Twitter, and Google Docs to share information about victims. During the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings, reddit and 4chan became active, if not infamous, spaces for trying to piece together the events and locate the terrorists.

Out of desperation, need, and extreme stress, everyday people work across multiple social media systems to communicate with each other about the wheres, whens, whys, and hows of disasters. They want to learn what happened, where it happened, who was affected, and what they can do to help.

Unfortunately, what have also remained somewhat consistent are the ham-fisted implementations of social media tools. We continue to present interfaces that may mean well, but are anti-social in their policies, interfaces, and information flow. We make it difficult to share content. We make it nearly impossible to verify information. And we often punish volunteers who are trying to share information by limiting their capacity to push and pull this content across multiple systems.

Focusing on these cases, we can also rethink the ways in which we configure our users as participants and ourselves as participating within these spaces. In order to create really useful software, we need to use this software in the ways in which our participants will use it. If we can reconsider our roles as participants as well as architects, designers, and developers, we will create better tools that can support more useful and productive communication. It behooves us to encourage participation in spaces where participation can lead to positive outcomes.

The Utility of Everyday Social Media Systems During Disasters

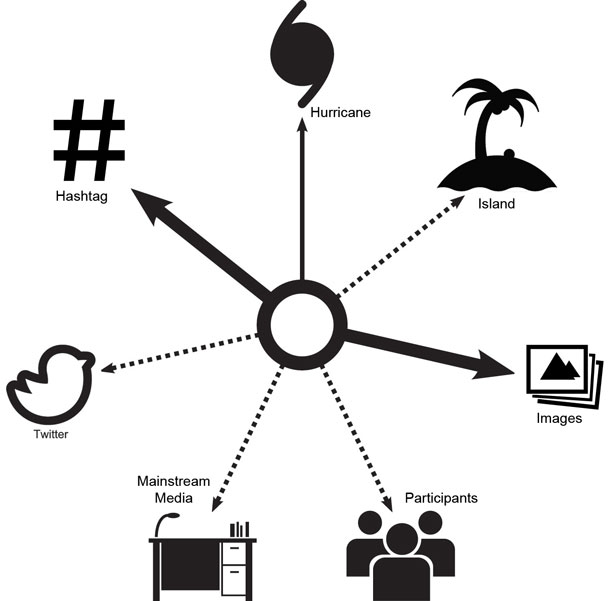

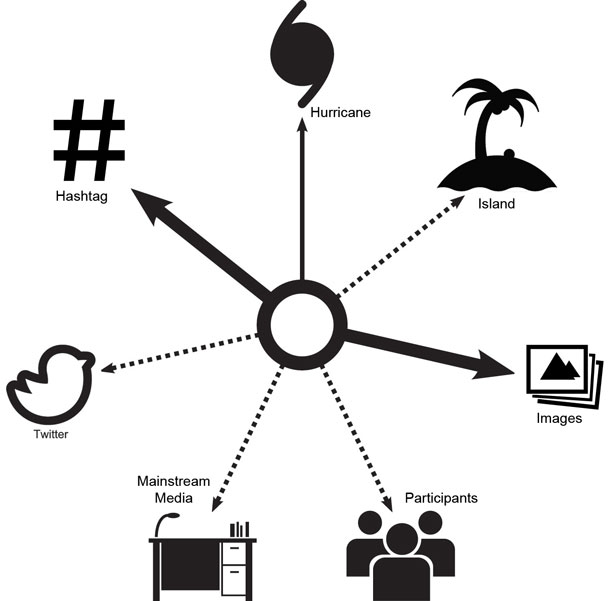

During times of disaster, everyday people tend to use the systems where they already have an established network or where they believe the appropriate audience can be found. These systems are already established before disasters, but the ways in which participants use these sites tends to greatly diverge from the use cases that the site developers had in mind when they were originally designed. Figure 1 illustrates an ecosystem of activity that could occur in the wake of a hurricane, with various people, places, and technologies reacting to this event. The lines in this diagram represent the most active nouns in this ecosystem: the hurricane itself, hashtags (whether they are on Twitter, Instagram, or elsewhere), and images. Understanding these ecosystems and the kinds of activities taking place in them is useful in mapping future directions for the designs and policies of the systems we create.

Think your website won’t become a space where people need to communicate during times of disaster? That may be true if you’re managing the community sites for Quicken, but I promise you that you will be surprised by what your participants do to the systems you create. It will be up to you to decide how to harness, support, or discourage this use, just as the site managers of BBC News had to decide how to handle comments about missing persons appended to news reports about the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, And how craigslist needed to figure out how to handle posts of missing persons in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. And whether Google would make it easy to trace flu reports, and how reddit needed to assess how they would handle the flood of posts during the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings.

Architecting Spaces for Participation

Our users are no longer satisfied to simply “use” whatever technology we put in front of them (if they ever were really “satisfied”). Instead, they are reaching out and participating in collaborative writing spaces such as Google Drive, having conversations using hashtags in Twitter, and pinning a variety of content to their Pinterest boards.

In the case of disaster, the need to locate information, connect to those in need, and share knowledge about an event becomes heightened and often desperate. What unites each of these experiences is the insatiable need to participate. So when we think of users, let’s reconfigure them as participants. In doing so, we can begin to see them as co-authors, collaborators, and even co-conspirators for the experiences we are architecting.

In order to get a handle on this kind of reconfiguration, we can focus on three major points:

1. Users as Participants

To build social websites, apps, and software, it’s useful to think of our users as participants. They aren’t simply using what we provide them—they are adding content, interacting with each other, and altering the system in ways that we should pay attention to, investigate further, and consider how we might support it. When you start thinking about users as participants, you can begin to question how your system supports their activities. Where can they share content? How can they share content? When do you want them to participate? Why are certain spaces more active than others?

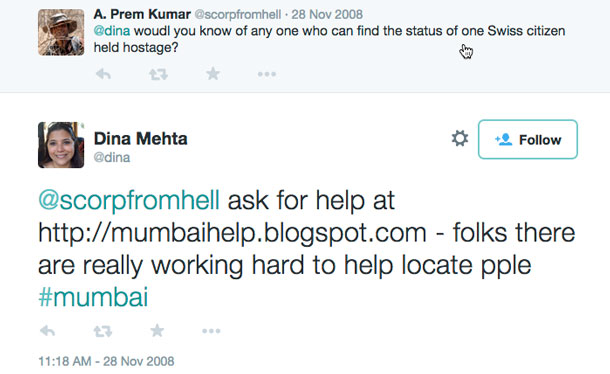

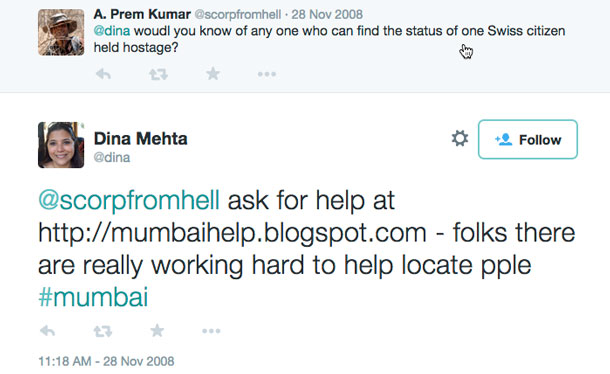

A major turning point for social web tools was Dina Mehta’s use of Twitter, blogs, and Google Sheets during the terrorist attacks in Mumbai. She and her colleagues’ work created a space where participants could volunteer, share, and engage with one another across multiple platforms. Without waiting for officials to help, they used these tools in ways in which the tool developers and designers never imagined: to help catalog those injured and deceased during a terrorist event. Figure 2 illustrates how Mehta used Twitter to encourage participation. Although we had witnessed participants using other tools in similar ways in earlier disasters, this coordinated activity across multiple systems using tools in ways other than their original intention was somewhat new. This moment, and the disasters that came next, led to several user experience innovations across mainstream news sites, as well as Google itself.

2. Architects as Participants

In order to design for participation, we must be participants in these spaces. Sounds simple, but how many of us are active users of the systems we create? Do we know how our users participate in our systems? What rules they bend in order to share content? What new innovations they might be creating on our own sites?

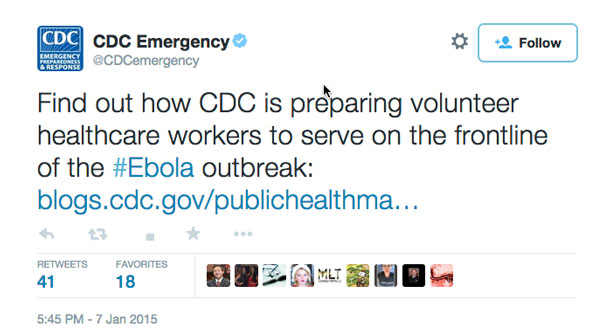

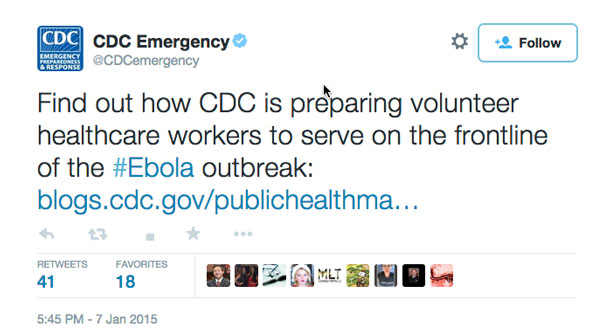

A recent example of this kind of activity is the new guidelines released by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) for hashtag standards to be used during emergencies. Studying recent disasters, including the Haiti earthquake of 2014, OCHA issued a number of guidelines on hashtag creation. For example, they propose using the name of the incident or activity plus the location when discussing specific disasters, such as #EbolaLR (Ebola in Liberia) and #EbolaGN (Ebola in Guinea). Figure 3 is an example of a more general use of the #Ebola hashtag. Their results are very similar to what my team and I found during the 2010 earthquake in New Zealand, and published in the SIGDOC proceedings in 2011. Hashtags on Twitter are a key component for communicating across cultures, peoples, and organizations. By participating in these spaces as experience architects we can begin to better understand how everyday people are using technology and how we, as designers and usability experts, might improve these experiences.

3. Supporting Anchor Participants

Learning how participants use your system will help clue you in to the key members on your site. Anchors are participants who help your system thrive. They aid newcomers, tag content, validate information in your forums, and share news with others. Who are the participants who are anchoring your system? How can you better support their work so they can thrive and continue their work?

A recent example of this kind of activity is the ways in which anchor participants work to share information about disasters on reddit. Through document design and community support, they are able to create posts that act as live updates about these events. Using bolding, bullet points, links, and other conventions, they can format information to show priority and share critical details, such as telephone numbers for non-profit and government agencies that can help victims. Through their “upvoting” and “downvoting” system, the community helps prioritize information and share new knowledge. These live updates do have limitations however, primarily due to the amount of text that can be added to any given post. But redditors have figured ways around this constraint, namely by creating a new post and linking to it.

Beginning in July 2014, anchor participants were given a new option: live posts. This interface combines the functionality of a blog with reddit comment threads. Clearly understanding the needs of their anchors, the /r/live section of reddit allows anchors to avoid the posting limits in the regular reddit thread while keeping their live content at the top of the page where it can easily be accessed and read by other participants. Figure 4 is an example of this kind of interface implementation.

![Screen shot from reddit: [LIVE] French manhunt for attackers of Charlie Hebdo, showing updates posted every 3-4 minutes from 12:34pm to 12:47 on 9 Jan](https://uxpamagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/15-1-Potts-Fig4_reddit.jpg)

Future Disasters, Future Participants

By using disaster as a case study, we can better understand the seriousness, the urgency, and the need for building systems that allow for participation. While these cases are extreme, they also point to underlying usability issues for everyday use. If we can think of our users as participants, our participation in our own systems, and our key members as anchors in our communities, we will better our systems and our experiences.

[greybox]

Credits for Figure 1

- Bird designed by Thomas Le Bas

- Desk designed by James Thoburn from The Noun Project

- Hash designed by P. J. Onori

- Hurricane designed by The Noun Project

- Island designed by Athena Manolopoulos

- Picture designed by mooooyai from The Noun Project

- User designed by Denis Chenu from The Noun Project

[/greybox]

在遭遇爆炸和飓风等灾难期间,人们每天都会使用社交媒体系统相互联系和建立网络。以下三个要点描述了社交媒体的这种使用场景:用户参与者、架构师参与者,以及支持锚点参与者。如果我们可以将用户视为参与者,同时考虑我们在自己的系统中的参与,以及我们的关键成员在社区中的锚点作用,那么我们就能更有效地设计我们的系统,提供更好的体验。

폭발과 허리케인 등의 재난 시에도, 사람들은 서로 연결하여 네트워크를 형성하는 여러 소셜 미디어 시스템들을 매일 사용합니다. 세 가지 관점에서 그들의 사용을 기술할 수 있습니다. 참여자로서의 사용자, 참여자로서의 설계자, 지지하는 닻과 같은 참여자가 그들입니다 . 우리가 사용자들을 우리의 시스템에 참여하는 참여자로, 우리의 주요 회원들을 커뮤니티를 지지하는 닻으로 생각할 수 있다면, 우리는 시스템과 우리의 경험을 더 훌륭하게 설계할 것입니다.

Em tempos de desastres, como bombardeios e furacões, pessoas comuns usam sistemas de mídia social para se conectar e estabelecer uma rede. Três pontos principais descrevem esse uso: usuários como participantes, arquitetos como participantes, participantes como âncoras de apoio. Se pudermos pensar em nossos usuários como participantes, nossa participação em nossos próprios sistemas e nossos principais membros como âncoras em nossas comunidades, projetaremos melhor nossos sistemas e nossas experiências.

O artigo completo está disponível somente em inglês.

爆撃やハリケーンといった災害が発生すると、人々は互いのつながりを維持し、ネットワークを築くための手段としてソーシャルメディアを利用する。そうした利用は、主に次の三点――すなわち、ソーシャルメディア参加者としてのユーザー、参加者としての設計者、参加者としての支援者――に分類することができる。参加者としてのユーザー、我々の我々自身のシステムへの参加、そしてコミュニティを支援する主要メンバーを意識することで、より優れたシステムやエクスペリエンスを設計することができるだろう。

En tiempos de desastres, como bombardeos y huracanes, las personas comunes recurren a las redes sociales para conectarse entre sí y establecer una red. Tres puntos principales describen su uso: usuarios como participantes, arquitectos como participantes y participantes pilares de apoyo. Si podemos ver a los usuarios como participantes, nuestra participación en nuestros propios sistemas y a los miembros clave como pilares en las comunidades, podremos diseñar mejor nuestros sistemas y experiencias.

Nuestras expectativas como usuarios han cambiado. Más que sólo leer contenido, queremos interactuar con él. Queremos dar opiniones compartir contenidos y distribuir información. Nuestra necesidad de participar se ha extendido a espacios que, como expertos en experiencia de usuario, nunca podríamos haber anticipado.

Esto es a menos que ya estamos participando en estos espacios, moviendo contenido de sitio en sitio, compartiéndolo en un ecosistema de actividad. Pero, ¿cuántos de nosotros pasamos tanto tiempo en esos espacios tal como lo hacen nuestros usuarios?. Y, ¿cuántos de nosotros hemos hecho el ejercicio de cambiar de ser “usuarios” a ser “participantes” – activos, contestatarios y no sòlo interesados en “usar” cualquiera sea el producto que les damos?

Para algunos de nosotros estos conceptos no son nuevos. Pero, ¿los practicamos en nuestro trabajo de diseño? Consideremos un caso extremo que nos permita empezar a pensar en estas cuestiones: el uso de redes sociales en tiempos de desastres. Y no una crisis simple como que Facebook se caiga o Twitter colapse. Estoy hablando de crisis grandes: bombardeos, huracanes, terrorismo, tsunamis, guerras, tornados…

La Necesidad de Experiencias de Usuario que estimulen la Participación

Usando el caso extremo del desastre podemos comenzar a considerar que los participantes en los diferentes tipos de comunicación se están tomando los tiempos y espacios usando herramientas de redes sociales.

Por casi 10 años he investigado, seguido y participado en múltiples posteos, discusiones, repositorios de fotos, hashtags, foros, chats, entradas y comentarios durante numerosos desastres. Desde el terremoto y tsunami en el 2004 en el Océano Índico hasta la caída del vuelo MH17 sobre Ucrania en el 2014, la necesidad de la gente de buscar información y distribuir contenido en las redes sociales ha permanecido consistente. En los albores del Huracán Katrina, craigslist se transformó en una herramienta de búsqueda de amigos y familiares en el área de Nueva Orleans. Cuando los terroristas atacaron Mombay, los expertos en redes sociales y los participantes usaron blogs, Twitter, y Google Docs para compartir información sobre las víctimas. Durante los bombardeos en la Maratón de Boston, las redes reddit y 4chan fueron espacios activos, y poco gratos, para tratar de recomponer los momentos de los ataques y localizar a los terroristas.

En medio de la desesperación, la necesidad y el stress máximo, la gente usa múltiples sistemas de redes sociales para comunicarse con otros sobre los dóndes, cuándos, por qués y cómos de los desastres. Quieren saber qué pasó, dónde pasó, quién se vio afectado y qué pueden hacer para ayudar.

Desafortunadamente lo que también ha permanecido como consistente son las torpes implementaciones de las herramientas de redes sociales. Seguimos presentando interfaces que tienen buenas intenciones, pero que son antisociales en sus políticas, interfaces, y flujos de información. Hacemos que el compartir contenido sea difícil. Hacemos que sea casi imposible verificar información. Y muchas veces castigamos a los voluntarios que tratan de compartir información limitando su capacidad de distribuir este contenido en múltiples sistemas.

Enfocándonos en estos casos, también podemos repensar las maneras en que configuramos a nuestros usuarios como participantes y a nosotros mismos como participantes en estos espacios. Para crear sistemas que sean realmente útiles, necesitamos usarlo en la manera en que nuestros participantes lo usuarán. Si podemos reconsiderar nuestros roles como participantes así como arquitectos, diseñadores y desarrolladoress, crearemos herramientas mejores que puedan apoyar una comunicación más útil y productiva. Nos lleva a estimular la participación en espacios en que la participación entrega resultados positivos.

La Utilidad de los Sistemas de Redes Sociales Durante Desastres

En tiempos de desastres, la gente tiende a usar sistemas donde ya tengan una red establecida o donde crean que se puede encontrar una audiencia apropiada. Estos sistemas han sido creados antes de los desastres, pero la manera en que los participantes usan estos sitios tiende a ser distinta de los casos de uso en que los desarrolladores pensaron cuando crearon originalmente los sitios. La Figura 1 ilustra un ecosistema que puede ocurrir en el evento de un huracán, con mucha gente, distintos lugares y tecnologías reaccionando ante el evento. Las líneas en este diagrama representan los sustantivos más activos en el ecosistema: el huracán mismo, hashtags (si es que están en Twitter, Instagram, o en otra parte), e imágenes. Entender estos ecosistemas y los tipos de actividades que suceden en ellos es útil para poder mapear futuras instrucciones en los diseños y políticas en los sistemas que creamos.

¿Piensas que tu sitio no va a ser un espacio donde la gente se necesite comunicar en tiempos de desastre? Eso puede ser verdad si estás administrando los sitios de las comunidades de Quicken, pero te aseguro que quedarás sorprendido con lo que tus participantes hacen en los sistemas que creas. Está en ti decidir si quieres hacerte o no cargo de este uso, tal como lo hicieron los administradores del sitio de BBC Noticias cuando debieron decidir cómo manejar los comentarios sobre personas perdidas en los reportes de las noticias sobre el terremoto y tsunami en el Océano Índico. Y cómo craigslist necesitó saber cómo manejar los posteos de personas perdidas durante el Huracán Katrina. Y si es que a Google se le hace fácil hacer el seguimiento de los reportes de gripe, y cómo reddit necesitó saber cómo enfrentar la marea de posteos que recibieron tras los bombardeos de la Maratón de Boston.

Diseñando Espacios para la Participación

Nuestros usuarios ya no están satisfechos con sólo “usar” cualquier tecnología que les pongamos al frente (si es que alguna vez estuvieron realmente “satisfechos”). En vez, están llegando y participando en espacios colaborativos como Google Drive, teniendo conversaciones usando hashtags en Twitter, y destacando una variedad de contenido en sus tableros de Pinterest.

En el caso de los desastres, la necesidad de localizar información, de conectar a quienes lo necesitan, y de compartir el conocimiento sobre un evento se ve reforzada y muchas veces, es desesperada. Lo que une a cada una de estas experiencias es la necesidad insaciable de participar. De manera de que cuando pensamos en usuarios, debemos reconfigurarlos como participantes. Debemos comenzar a verlos como co-autores, colaboradores, e incluso co-conspiradores en las experiencias que estamos diseñando.

De manera de poder ordenar este tipo de reconfiguración, nos podemos centrar en tres puntos focales:

1. Usuarios como Participantes

Para construir sitios sociales, aplicaciones y software, es útil pensar en nuestros usuarios como participantes. Ellos no sólo están usando lo que les entregamos—ellos están añadiendo contenido, interactuando, y alterando el sistema en maneras en que debemos ponerles atención, investogar y considerar en apoyarlas. Cuando empiezas a pensar en tus usuarios como participantes, te comienzas a preguntar de qué manera tu sistema los ayuda en sus actividades. ¿Dónde pueden compartir contenidos? ¿Cómo pueden compartir contenidos? ¿Cuándo queremos que participen? ¿Por eué hay ciertos espacios más activos que otros?

Un punto de inflexión en las herramientas sociales fue el uso que le dio Dina Mehta a Twitter, los blogs, y Google Sheets durannte los ataques terroristas de Mombay. Su trabajo y el de sus colegas creó un espacio donde participantes podían realizar trabajo voluntario, compartir, y comprometerse unos con otros en múltiples plataformas. Sin esperar la ayuda oficial, usaron estas herramientas en maneras en que ni los desarrolladores ni los diseñadores de esas herramientas, imaginaron alguna vez: para ayudarles a catalogar a los heridos y muertos en un evento terrorista. La Figura 2 ilustra cómo Mehta usó Twitter para incenyivar la participación. A pesar de que hemos sido testigos que han habido otros participantes que han usado otras herramientas en maneras similares en desastres anteriores, la actividad coordinada en múltiples sistemas usando herramientas de maneras en que no fueran concebidas originalmente, fue algo nuevo. Este momento, y los desastres que vinieron después, llevó a muchas innovaciones en la experiencia de usuario de sitios de noticias, tal como el mismo Google.

2. Arquitectos como Participantes

Para diseñar para la participación, debemos ser participantes en estos espacios. Suena simple, pero ¿cuántos de nosotros somos usuarios activos de los sistemas que creamos? ¿Sabemos cómo nuestros usuarios participan en nuestros sistemas? ¿Qué reglas quiebran para poder compartir contenido? ¿Qué nuevas innovaciones pueden crear en nuestros sitios?

Un ejemplo reciente de este tipo de actividad son las nuevas directrices de la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas para la Coordinación de los Asuntos Humanitarios (OCHA, por sus siglas en inglés) respecto a los estándares de hashtag que deben ser usados durante emergencias. Al estudiar desastres recientes, incluyendo el terremoto de Haití de 2014, OCHA creó una serie de guías en la creación de hashtag. Por ejemplo, ellos propusieron usar el nombre del incidente o la actividad y su locación al discutir sobre desastres específicos, tales como #EbolaLR (Ebola en Liberia) y #EbolaGN (Ebola en Guinea). La Figura 3 es un ejemplo de un uso más general del hashtag #Ebola. Los resultados son muy similares a los que mi equipo y yo encontramos durante el terremoto de 2010 en Nueva Zelanda, y publicamos en los procedimientos de SIGDOC en 2011. Los hashtags en Twitter son componentes clave para comunicarse entre culturas, personas y organizaciones. Al participar en estos espacios como arquitectos de experiencia podemos entender mejor cómo la gente usa la tecnología y cómo nosotros, como diseñadores y expertos en usabilidad, debemos mejorar esas experiencias.

3. Apoyando a Participantes Ancla

Aprender sobre cómo los participantes usan tu sistema te ayudará a saber cuáles son los miembros clave de tu sitio. Las anclas son participantes que ayudan a que tu sistema se mueva. Buscan a participantes nuevos, etiquetan contenido, validan información en tus foros, y comparten noticias con otros. ¿Quiénes son los participantes que están anclando tu sistema? ¿Cómo los puedes apoyar en su trabajo de manera de que puedan seguirse moviendo y continuando su trabajo?

Un ejemplo reciente de este tipo de actividad es la manera en que los participantes ancla trabajan para compartir información sobre desastres en reddit. A través del diseño de documentos y de apoyo de la comunidad, son capaces de crear posteos que actúan como actualizaciones en vivo sobre estos eventos. Usando negritas, listas, enlaces, y otras convenciones, pueden formatear inforación para priorizarla y compartir detalles críticos, como números de teléfono de agencias gubernamentales y sin fines de lucro que puedan ayudar a las víctimas. Mediante su sistema de votos “a favor” y “en contra”, la comunidad ayuda a priorizar la información y a compartir conocimiento nuevo. Estas actualizaciones en vivo, sin embargo, tienen limitaciones, primariamente debido a la cantidad de texto que se le puede poner al posteo. Pero los editores de reddit han encontrado maneras de saltarse esta limitación, creando nuevos posteos y poniendo enlaces hacia él.

Desde julio de 2014, los participantes ancla tuvieron una nueva opción: posteos en vivo. Esta interfaz combina la funcionalidad de un blog con los comentarios de reddit. Entendiendo claramente las necesidades de sus anclas, la sección /r/live de reddit permite a los anclas saltarse las limitaciones en los posteos regulares de reddit manteniendo su contenido en vivo al principio de la página donde puede ser accesado y leído fácilmente por otros participantes. La Figura 4 es un ejemplo de este tipo de implementación de la interfaz.

![Screen shot from reddit: [LIVE] French manhunt for attackers of Charlie Hebdo, showing updates posted every 3-4 minutes from 12:34pm to 12:47 on 9 Jan](https://uxpamagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/15-1-Potts-Fig4_reddit.jpg)

Futuros Desastres, Futuros Participantes

Usando a los desastres como caso de estudio, podemos entender mejor la seriedad, urgencia, y la necesidad de crear sistemas que permitan la participación. Si bien estos casos son extremos, apuntan a aspectos que subyacen la usabilidad del uso diario. Si pensamos en nuestros usuarios como participantes, nuestra participación en nuestros propios sistemas, y en nuestros miembros clave como anclas en nuestras comunidades, mejoraremos nuestros sistemas y nuestras experiencias.

[greybox]

Créditos para la Figura 1

- Pájaro diseñado por Thomas Le Bas

- Escritorio diseñado por James Thoburn de The Noun Project

- Hash diseñado por P. J. Onori

- Huracán diseñado por The Noun Project

- Isla diseñada por Athena Manolopoulos

- Imagen diseñada por mooooyai de The Noun Project

- Usuario diseñado por Denis Chenu de The Noun Project

[/greybox]