The topic of inspiration for this article is of focus. Inspiration is omnipresent in fields of design and product innovation. Nevertheless, it is often structured by intuition and not based on knowledge or models. Looking at the wider topic, there exist numerous publications about innovation and connected topics like Design Thinking. In the connected topic of idea creation there are papers showing outcomes of field research to identify some core aspects (see for example a paper for the projecthouse METEOR (in German) or WeTransfer’s Ideas Report).

Former studies and publications focused more on the “unusual” fields of idea origination; respectively, the environments that people think are the most inspiring. In a 2005 paper by Urs Fueglistaller, he mentioned that 24% of design ideas originate within an organization and 74% are adapted from external sources and other organizations. In a 2011 paper by Jens Mühlstedt and colleagues, they mentioned that 70% of people are inspired by the natural environment of a forest, 63% by music, and 54% by the “outdoors.”

Newer research shows how idea generation occurs—the actual core part of inspiration. As the 2018 WeTransfer’s Ideas Report showed out of 10,000 surveyed participants, 47% mention their ideas are created “at work / my desk / in my studio,” 29% “on my way to/from work,” and 23% “in bed.” In addition, the report mentions sources of inspiration, with 45% mentioning “books/magazines,” 45% “talking with friends,” 38% “travel,” 35% “music,” and 34% “nature.” This shows that inspiration and ideation must be clearly distinguished and examined separately although they are both part of innovation.

For innovation and idea creation there are numerous methods and materials available that explain the psychology behind ideation processes and provide tools and templates as well as case studies and examples. However, for the topic of inspiration, especially in a professional environment, there are fewer resources. Hence, in this article the process of work-related inspiration is discussed and disassembled into three defined phases. Each phase is explained in different aspects that include connected methods and recommended tools for each phase. Because this model was created through the observation of several exercises, workshops, and projects, it should be noted that no additional empirical study has been conducted.

Terms and Definitions

The meaning of certain relevant terms are explained below (based on their usage at the design agency where I work).

- Creativity is the ability to create original ideas with high impact or disruption rate; it also includes all aspects of personal idea creation, especially the methods and materials supporting this and the involvement of uncommon ideas.

- Ideation is the process of creating, selecting, and refining ideas.

- Inspiration is the moment of creating a new idea; it also is the environmental setup that provides individuals with an appropriate atmosphere for idea development.

- Innovation is the consideration of business goals during design or product ideation.

Phases of Inspiration

Inspiration processes in design often occur quite intuitively. Structure, methods, and materials are planned based on the experience of those involved, which often leads to good results. Nonetheless, more procedural knowledge about mental models and psycho-social motivations has shown the potential to support inspiration processes and increase the number and quality of resulting ideas.

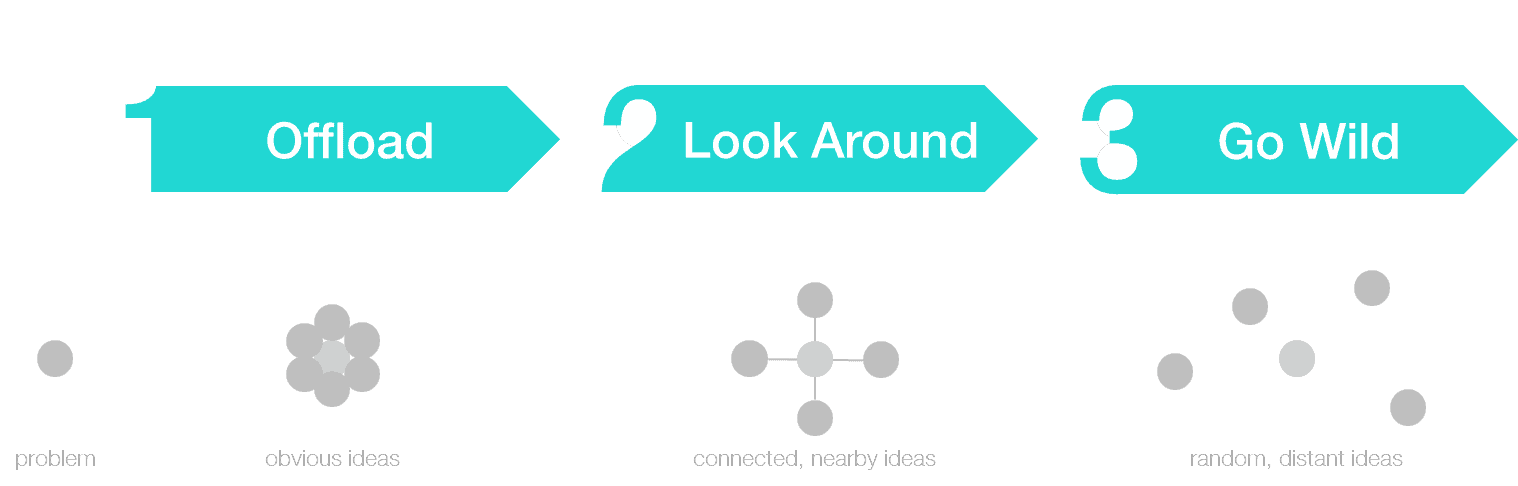

In several years of working in fields of human-machine interaction science at a university and several years of working in UX and innovation for a strategic product design agency, I participated in and conducted numerous ideation workshops with the purpose to get possible solutions for a problem. There, a typical flow indicated three main phases: “offload” obvious ideas, “look around” to find nearby and connected ideas, and “go wild” to collect random, distant ideas (see Figure 1). Ideation tasks are quite individual, so the phases can be swapped or omitted. However, these phases tend to explain the typical sequence of inspiration, as I have witnessed them to occur, and help to structure workshops and processes for product design.

Figure 1. The 3 Phases of Inspiration: Offload, Look Around, and Go Wild.

Precondition: A Problem

If an area of innovation, or problem space, is too wide or too narrow it can prohibit an individual or group from creating ideas. If the field is too narrow, it might be difficult for designers to generate good ideas because the problem definition already includes a solution, for example, a design prompt such as “Ideate a good caption for the ‘OK’ button.” Here, the individual or group asked to create ideas cannot come up with a different and maybe better solution, such as an automatic forwarding or speech input, because they have been already limited to a solution by the prompt—the button. If the field is too wide, this can be an even bigger problem. Either the individual or group may struggle to define the problem, which means the focus is taken away from generating ideas, or the field is just too vague and general to create meaningful inspiration. An example would be “Create new solutions to buy things!” This prompt is unclear regarding the definition of “things,” “buy,” a target audience or customers, and so on. Even if ideas are created, they might not answer the problem the prompt seeks to address.

A good way to deal with this precondition is to ensure the problem is properly defined. First, a rough definition of the question, the use case, or the innovation field must be created.

- If the problem statement is formulated in a short sentence, that might be enough to provide clarity or direction.

- It may also help to frame the problem in the form of a use case. For example, “As a _____ (role), I want to _____ (action) to _____ (objective).”

- It can also help to frame the problem in the form of a how-might-we question: “How might we _____ (user need)?” or “How might we _____ (action) _____ (what) for _____ (stakeholder) in order to _____ (what change)?”

If this problem definition is not done by the “client,” it can be done by the project team as well. Helpful methods can be re-briefings, scoping workshops, stakeholder interviews, requirement workshops, or just several discussions among the design team. Only after the objective or problem statement is properly defined is it time to initiate the inspiration phases.

Phase 1: Offload

When ideation starts, much has already occurred. For example, conversations like briefings, kick-off discussions, project management operations, and design research may have already taken place. Usually, in these preparation tasks, design ideas have surfaced.

To start the ideation, existing ideas must be expressed.

Figure 2. A metaphor for Phase 1: Offload is the well-known phrase “low hanging fruit”—easy to reach, but requires effort to cultivate.

Offloading means that ideas must be written down, verbalized in a group meeting, or somehow brought to expression. People need to see their thoughts in words or sketches, or at least communicate them to others. Also, it is challenging to keep more than a few ideas in the short-term memory (the famous 7 plus minus 2 chunks of Miller, 1956) so writing them down ensures none are forgotten or disregarded. After expressing several ideas, people performing ideation feel ready to deal with new topics, think about questions, connect thoughts, form them into more robust ideas, and add their thoughts to the solution space.

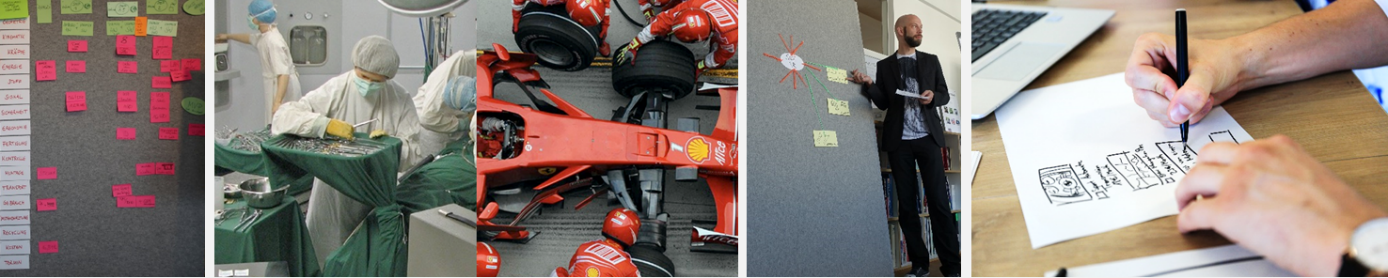

Experience shows a bit of pressure can force the creation of unconscious ideas, for example, being summoned to a room with pen and paper in hand to write down ideas in 10 minutes. The following are helpful methods and materials for this phase (also see Figure 3):

- Brainstorming: Express and discuss the ideas in a group.

- Brainwriting: Write down all ideas, both small and large, on Post-it notes.

- Note taking: List ideas, even informally and in short hand, as notes on paper.

Figure 3. Examples of Methods in Phase 1: Offload—note taking, brainwriting, brainstorming.

Phase 2: Look Around

Now that initial thoughts and ideas have been addressed, the task of ideation can be brought to the next level. This is done by analyzing different aspects of the problem, connecting nearby fields, and investigating if they inspire people to come up with new ideas. It could help to explore technologies, to look at user needs, to discuss business opportunities, or to just look at the components of your product and analyze them step by step.

To perform inspiration close to the first ideas, related topics should be systematically investigated.

Figure 4. In comparison to the first phase, more effort is needed to reach the second batch of ideas.

The overall approach is to divide the problem and solution spaces into sub-elements and look at every component and to investigate if there are opportunities for new ideas and thoughts. So, a product can be divided into parts, a question can be further explored with follow-up questions, and tasks can be disassembled into even more focused sub-elements. Mostly, it also helps to look at different users and roles, to discuss technologies, to analyze processes, to investigate touchpoints and interactions, to gather business aspects, and to get insights about markets.

This second phase sometimes leads to dead ends, but retracing steps can help get back on track. Often, it is useful to perform this second step in different settings and with different participants: alone, in groups, with the client, with future users, or with stakeholders. The following are examples of the numerous materials and methods that are available (also see Figure 5):

- Mind-mapping: De-cluster the question in several topics and go one or two steps in each direction.

- How-might-we: Ideate on several how-might-we questions.

- Solution sketching: Draw ideas and solutions to jump start inspiration.

- Competitor analysis and benchmarking: Investigate existing products to better understand the landscape of the problem area and to develop potential solutions.

- Analogies and comparable problems: Reflect on similar issues in other domains and work to discover their solutions.

- Crazy 8: Quick sketch eight ideas and solutions to generate creative ideas.

- Method 635: Use this engineer-oriented method of using one another’s ideas as jumping off points to create new ideas.

- Requirement lists: Use requirement lists, which are often created by engineers, to scope possible solutions.

Figure 5. Examples of methods in Phase 2: Look Around—requirement list, analogy example, mind-mapping, and solution sketching.

Phase 3: Go Wild

At this phase, brainstorming and ideation may seem exhausted or “exploited,” but there is the possibility to dig even deeper and start a third round of idea generation. In this phase, unexpected connections, not-obvious solutions, or outside-of-the-box ideas can be created to inspire the team above and beyond the boundaries of already expressed ideas. Even ideas that seem useless at first glance can lead to something innovative, productive, and useful.

To expand thinking even further and create more distant ideas, special methods can inspire people.

Figure 6. To generate more ideas, innovative approaches for ideation are needed.

One of the fundamentals of ideation is that there are no stupid ideas. In Phase 3 this is even truer than in earlier phases—even ideas that seem unproductive or unrelated on the surface can inspire people and lead to actionable solutions. At least it is fun to explore the boundaries of ideation (and beyond) which is an important part of group dynamics. An aspect of this phase is the idea that everything that is not “nearby” is helpful. This can mean talking to experts from different domains or sharing ideas with groups outside the project. This part of inspiration is often less structured and sometimes even ignored. It can be unclear which directions lead to new positive ideas, as well as when to end the ideating—you must rely on your gut. This final phase can also seem less important but may convince others, such as stakeholders, that every last idea was thoroughly explored as part of the process. And sometimes, the best idea comes from such a crazy excursion.

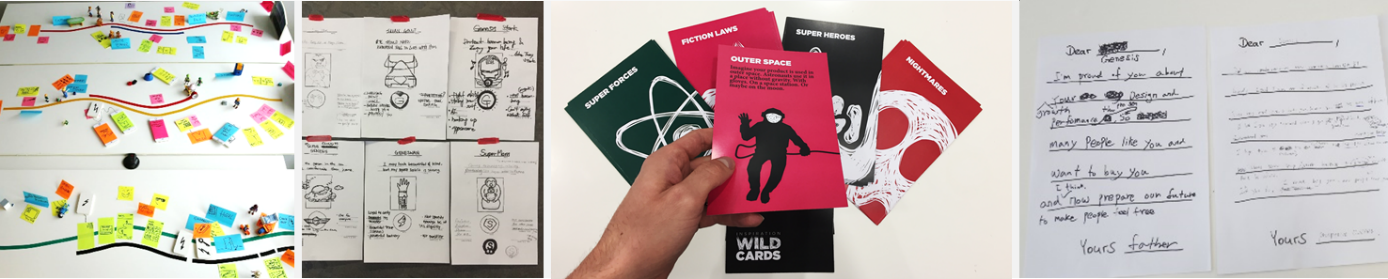

To perform the task of “going wild” in order to create this idea generation spread or question twist, use some of the following helpful methods (see also Figure 7):

- Mood boards / image boards: Increase inspiration by getting visual and connecting unconnected images to the solution space.

- Flip flop: Flip around the question and develop ideas for the opposite question, then flop them back to the initial space in order to gain a new perspective.

- Love letter / breakup letter: Write a short letter to the questioner or brand so the problem becomes personalized and ideas can be created for this specific “person.”

- Super hero / villain: Imagine the objective as a supernatural entity which can lead to new or unexpected ideas.

- Inspiration cards: Use card decks like “Inspiration Wild Cards” (Mühlstedt, publication pending), the “Tarot Cards of Tech” by Artefact, “Disrupt Cards” by Maluf, Singer, and Gonen, or “Don’t/Do This Game” by Roos to trigger random solution fields and problem areas that inspire for uncommon ideas.

For several of the methods there are quite good instructions, resources, templates, and manuals in print (e.g., the “The Pocket Universal Methods of Design” by Hanington and Martin, “Design. Think. Make. Break. Repeat. A Handbook of Methods” by Tomitsch and Wrigley, and “The Design Thinking Handbook” by Uebernickel and Brenner) and in numerous online sources.

Figure 7. Examples of Methods in Phase 3: Go Wild—user journey walkthrough, superhero, inspiration wild cards, and love letter.

Next Steps

There are several options for next steps after the inspiration phases have been completed. It should be clear that inspiration exercises and idea creation are never performed in isolation. Most likely, ideation and inspiration tasks are flanked by preparation and post-processing methods, as described in the following lists.

Preparational Methods

- Desk research: Conduct exploratory research about the topic or problem, previous products, the domain, and the customers.

- User research: Observe or shadow, interview, or conduct questionnaires with a customer base or a target audience.

- Stakeholder interviews: Source strategic knowledge around the business goals or needs of the problem, as well as develop details about roadmaps, technical paths, or management.

- “Client” discussions: Define the project’s objectives, scope, boundaries, and the planned working packages to deliver the objectives.

Post-processing Methods

- Ratings: Use dot voting, card sorting, and so on to organize and prioritize ideas.

- Storytelling: Develop user journeys, user journey maps, day-in-a-life story boarding, and service blueprinting to better understand the problem and solutions.

- Detailing: Use sketching, wireframing, cognitive walkthroughs, and so on to visualize a solution.

- Prototyping: Use experience prototyping, functional prototyping, and mock-ups to follow-up on design ideas.

- Testing: Conduct feasibility tests, ergonomic examinations, technology explorations, usability testing, and so on to validate and further explore design ideas.

Methods like these are also considered as part of the overall innovation process and described further in other literature (e.g., “15 Essential Books on Innovation”).

Individuals vs. Groups

One aspect of the inspiration and ideation process that should be investigated further is the inspiration practices of individuals versus groups. Both individuals and groups can perform exercises in all three phases discussed in this article. However, it should be noted that there are specific differences and nuances between individual and group work.

For example, in group work, conversations occur naturally. These conversations often lead to new thoughts and greater idea generation because they involve building on the suggestion of others. Group work can become unproductive if individuals dominate the discussion or focus too long on a specific topic without moving on. Hence, when performing group inspiration exercises, every participant should play a significant role. Before starting a conversation, everybody should take time to express their initial thoughts in quiet exercises. Groups are also good for the immediate rating and filtering of ideas.

Individuals need time on their own to think about a certain topic and to be clear on at least some aspects. So silent phases should be the beginning of creating ideas. Individuals might also need more triggers to come up with new thoughts. So, it could help to do Phases 2 or 3 repeatedly if performing them alone. Also, there could be mental blocks as groups start creating and developing ideas. Hence, forced time slots for Phase 1 could be beneficial for speeding up the ideation process and unblocking any inspiration. At some point, it becomes necessary to switch to group exercises to let the ideas grow and to receive feedback.

In most cases ideation starts with the individual and later expands to groups.

In all observed and conducted projects and workshops, both the tasks of individuals and of groups have been part of the process. It seems to be positive and productive to integrate both in alternating order and various configurations to get to the optimal output from the inspiration phases.

Summary and Outlook

The three phases of inspiration seem to be a good framework for structuring ideation processes, arranging ideation phases, and ensuring the use of the right approaches. Sorting the cognitive processes helps in starting the right thing at the right time. Methods and materials for Phase 1 and 2 have been heavily discussed and are now regarded as common practices in the design world, and resources and documentation are readily available. So far, it seems that less research has been performed on Phase 3, therefore resulting in a lack of methods and materials. There is a need to work on a greater variety of resources and methods for this phase.

Further research should investigate which psychological effects lie behind the three phases, as well as all the ideation subtasks of individuals and groups. One crucial question to consider investigating is if there is an ideal timeframe for individual versus group ideation. For example, when is an ideal point to transition from individual to group ideation? When are individuals ready to share ideas with others, and when do they need more input or time on their own? Answering these questions could lead to a more formalized framework and even more efficient ideation practices. In addition, methods and tools to collect the right ideas as they occur are also underdeveloped. And finally, inspiration is strongly connected to intrinsic motivation—so clients, employers, and project teams should always keep in mind that people must be able, willing, and allowed to ideate in order to generate meaningful and productive solutions.