The use of information and communications technologies (ICT) in healthcare has been heralded as a potential solution to issues of high cost, poor quality, and unsatisfactory patient care experience. However, the use of ICT to deliver safe and sustainable healthcare systems has been described as a “wicked problem,” referring to the complex web of stakeholders, systems, and legislative parameters involved. Because of its complexity, inherent unpredictability, and often erratic nature, the use of ICT in the healthcare system requires unique attention to context.

In the U.S., the 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act) established the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). It also introduced the terms “meaningful use” of “certified EHR technology” and offered incentive payments to eligible professionals and hospitals. The Meaningful Use program is built on the concept that certified electronic health record (EHR) use may improve quality, safety, efficiency, and reduce health disparities. Related goals include actively engaging patients and their families in quality care, improving care coordination, and informing population and public health.

The basic idea is that collectively these practices would lead to better clinical outcomes, improved population health outcomes, increased transparency and efficiency, empowered individuals, more robust research data on health systems, and would help maintain privacy and security of patient health information.

The result has been rapidly increased use of EHRs. The US Department of Health and Human Services estimates that use of an EHR by office-based physician practices was up to 78% in 2013 (from 18% in 2001) and 89% of critical access hospitals were using EHRs by the end of 2013.

Despite widespread use however, most of us have had bad experiences with the usability of EHRs. EHR usability is a significant weakness in healthcare, stifling efforts to demonstrate improvements in efficacy or quality of care. While this may stem from a lack of focus on usability in the process of ramping up EHR use, it is also caused by poor translation of existing and well known best practices to ensure usability from the field of design in healthcare. In many cases, the user interface for EHRs might best be described as a harkening back to the days of MS-DOS. There is substantial room for improvement in the design of EHR systems. Unfortunately, because EHRs often require complex technical integration, design and usability are often an afterthought and fail to incorporate a robust user-centered design process (see Figure 1) or full scale usability testing.

The Stakeholder Environment

The stakeholders in the healthcare UX environment are a diverse group, including both a wide range of people and an equally diverse world of devices and systems, all of whom interact with the EHR in some way. When rule number one is to “know your audience,” what do you do when your audience is this diverse in terms of both the range of stakeholder types and the tasks performed? Perhaps the best recommendation is to think about them in groups.

Clinicians

The use of new technologies like netbooks, tablets, mini-tablets, smartphones, and connected eyewear in the clinical encounter has only increased the likelihood that your primary care doctor is a key actor in selecting and maintaining your EHR. Still, much of the work involved in creating and maintaining EHRs falls to other members of your clinical team. For a designer, this means that understanding not just the different clinical roles, but also the workflow and the (often hierarchical) work system are important elements of usability.

Vendors and systems engineers

You might not think of the people who design EHRs as stakeholders, but when so many systems must work together, the environment in which products are developed must be considered. There are two groups of EHRs, developed in different ways:

- One group of products was developed at the grass roots by hospital or medical organizations with vision and technical capabilities aiming to meet their own needs.

- The other started as a niche market for technology companies with experience into existing systems in medicine.

Today, in the name of interoperability, grass roots EHRs are being replaced by systems from large companies like Cerner, Epic, Allscripts, and GE. These new products are helping define the emerging UI/UX of EHR systems. With both development experience and technological capacity, these companies work across disparate systems—from radiology images and laboratory results to claims and billing—and they offer a unique perspective on design and implementation, at least for specific use cases.

Unfortunately, because EHRs often require complex technical integration, design and usability are often an afterthought and fail to incorporate a robust user-centered design process or full scale usability testing.

Patients

At some time we are all likely to be patients. The information needed for diagnosis and treatment should be patient-centered. It should be available to us wherever we are (interoperable), and it should result in safe and effective treatment. And, this information should be maintained in a secure and private manner, giving individual patients control of how this information is shared.

Integration of systems and devices

EHRs require data across a group of integrated, previously stand-alone, systems. Examples include products to manage laboratory results, claims information, medications, medical history, and a wide variety of other clinical systems and encounter information. Creating even a loose digital connection between these different sources can be difficult and use can be limited. Together, a variety of efforts to create guidelines and standards for EHR documentation (for example, Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms and Clinical Document Architecture), information transport (for example, Health Level 7 messaging, the Direct Project), and security while maintaining patient confidentiality according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), substantially improves the overall functionality of EHRs.

Agency or government

Public health agencies also use information systems that are not necessarily well integrated either within the agency, between agencies, or between the agency and the rest of the healthcare system. Examples include information on disease surveillance and epidemiology, immunizations, and environmental health. Using data contained in an EHR to facilitate these public health activities can be a substantial benefit in improving the health of an overall population.

The Case for Guidelines

User-centered design, where the user is centrally involved in all stages of the design process, is critical to improving the design of EHRs. Finding common guidelines is not simple when the user environment is diverse and the tasks performed within the system range from simple to highly specialized.

One organization, the National Center for Cognitive Informatics & Decision Making in Healthcare (NCCD), is working on an HTML5 based publication the “Inspired EHRs: Designing for Clinicians iBook.” The aim is to provide more detailed guidance on issues of design for EHRs and the clinical environment. The current working prototype of the iBook focuses on the essential human factors that affect perception, like seeking familiar patterns or our tendency to seek out whole shapes rather than individual parts. It also includes design principles covering topics from the development of a mental model to addressing complexity and the use of color.

Established techniques and guidelines can provide both broad overarching principles and help facilitate local, detailed elements of a given implementation.

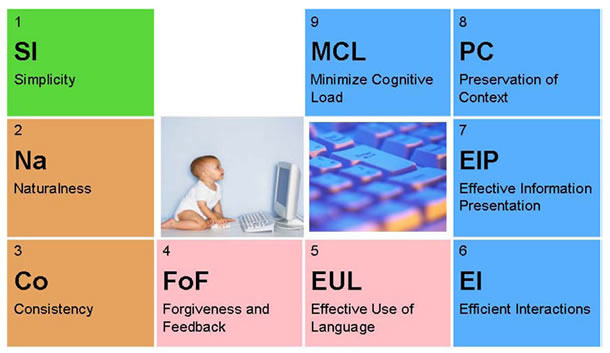

Overarching Guidelines

Some guidelines, like those outlined by the NCCD apply broadly to all implementations of an EHR. They are intended to help guide the designer on the fundamental tenets of design which help ensure proper usability.

Localization

In virtually all EHR implementations there are design implications to the localization of the system that can significantly impact usability. These are often the result of ad hoc configurations or accommodations focused on the integration of existing systems and any limitations that this process might surface. They also tend to facilitate existing best practices for a given healthcare system and the successful workflows that support those practices, even when not universal for a given EHR. More often than not, this means that EHR implementation, regardless of the relative robustness of a vendor system, is highly customized for a given environment or context. To be successful, UX designers need to bring both an understanding of good practice as well as a willingness to apply design guidelines to specific problems encountered in implementation.

Implications for a UX Designer

Just as a designer considers the difference between a first time user and a repeat user, designers who are new to the healthcare domain need to consider how this context represents some unique challenges.

- Today’s EHR implementations still have problems with system integration that can make it hard to design seamless workflows with good usability.

- There are many uses of the data the EHR maintains besides its primary function of displaying a patient record. Often called clinical data warehouses, these systems, often database driven, support a wide variety of research and surveillance activities aimed at improving quality and require their own interface guidelines.

- Usability methods need to consider the entire socio-technical system, not just the individual user.

In healthcare systems design, the aphorism says: “If content is King, context is God.” In this environment, the users are diverse, they interact with the system at a variety of different levels performing a range of work tasks from simple to complex, and they are almost always making tradeoffs based on time or resource limitations. But, today’s focus on meaningful use of electronic health records represents an unprecedented opportunity to refine the design process in this domain and bring a fundamental understanding of the impact of usability back into the design and development of EHRs.

If you are interested in working in healthcare design, it’s the perfect time. Vendors and hospital systems are both seeking out designers with relevant usability expertise. Go get involved!

[greybox]

Text in Figure 1: User Centered Design Process

The diagram shows three concentric rings of elements of a UCD process.

The inner ring has three main areas of work

- Identify

- Analyze (SMART-approach)

- Implement

The middle ring elaborates

- Engage Stakeholders

- Solicit Feedback

- Identify Requirements

- Apply SMART

- Gather Feedback

- Prioritize

- Test

- Launch

- Evaluate

The outer ring has values and benefits

- Increase exposure

- Active communication

- Improve credibility

- Foster Trust

- Reduce Resource Burden

- Integrate Public Heath and IT

- Increase utilization

- Improve performance

- Transparency

[/greybox]电子健康档案虽然获得广泛应用,但是其用户体验仍然普遍很差。它们没有充分采用可用性方面的最佳做法,也没有考虑使用背景上的重要差异:用户是多元化的,他们在各种不同的层级与系统交互,执行从简单到复杂的一系列工作任务,并且几乎总是需要根据时间或资源限制做出权衡取舍。 文章全文为英文版

광범위하게 사용되고 있다 하더라도, 여전히 사용자 경험이 좋지 않은 전자의료기록이 많습니다. 사용성의 우수사례는 활용되지 않고, 상황의 중대한 차이가 고려됩니다. 즉, 다양한 사용자들이 각자 서로 다른 수준에서 시스템과 상호작용하며 단순 업무에서 복잡한 업무에 이르기까지 다양한 업무를 수행하고 있고, 항상 제한된 시간이나 자원에 기반을 두고 최적점을 찾아가고 있습니다. 전체 기사는 영어로만 제공됩니다.

Apesar do amplo uso, muitos registros médicos eletrônicos ainda representam uma experiência negativa para o usuário. Eles não fazem uso de melhores práticas em usabilidade, e levam em consideração a diferença básica no contexto: os usuários são diversificados, interagem com o sistema em vários níveis distintos, desempenhando uma ampla gama de tarefas de trabalho, desde as mais simples até as mais complexas, e quase sempre enfrentam dilemas resultantes de limitações de tempo ou recurso. O artigo completo está disponível somente em inglês.

電子医療記録の多くは、広く使用されてはいるが、未だにユーザーエクスペリエンスに対する配慮に欠ける。これはユーザビリティにおけるベストプラクティスが実施されず、利用状況の決定的な違いが考慮されないためである。すなわち、ユーザーは多様であり、単純なものから高度なものまで広範にわたる作業を行うために、さまざまな段階でシステムを操作し、必ずと言っていいほど時間もしくはリソースの制約のため妥協しなければならないことを考慮していないのである。原文は英語だけになります

A pesar de su uso extendido, muchos historiales clínicos electrónicos aún ofrecen una mala experiencia de usuario. No emplean las mejores prácticas de usabilidad y no toman en cuenta la diferencia crítica en el contexto: los usuarios son diversos, interactúan con el sistema a diferentes niveles y desempeñan un rango de tareas de trabajo de simples a complejas, y casi siempre deben compensar las limitaciones de tiempo o recursos. La versión completa de este artículo está sólo disponible en inglés